He who is learning to paint must first learn to still his heart, thus to clarify his understanding and increase his wisdom. - From the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, 17th century.

Chinese Artist Converts Through Study of Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts

Some of you might already be aware of the conversion of a Chinese artist, Yan Zu, to Catholicism, as recounted on National Catholic Register and Catholic News Agency. A Dominican friar from the Western Province, who is from Taiwan originally, recently brought this story to my attention.

It was the study of European art history, and specifically medieval illuminated manuscripts that brought Yan to the Faith. She has a Chinese language blog, here, from which these images of her own work are taken.

This story is interesting to me for a couple of reasons. First, I am wondering if this is further indication of a natural affinity between Chinese and European figurative art, that allows for mutual influence to occur very easily. (I wrote about this in detail here.) The style of the traditional Chinese landscape, is formed by a Doaist worldview in which the material world directs us, through its beauty to heaven, which is a non-material realm of perfect order. Christian artists of the West might articulate just the same goal for their landscape painting, especially those painting in the baroque tradition. The difference is that for the Christian, heaven is occupied, so to speak, by God and his saints and angels.

Second, it seems to suggest that traditional Christian culture is as much universal as it is specific to particular times and places. If we were set the task in advance of dreaming up an art form that would convert Chinese people, many would say that we should adapt something that is of the Chinese culture into a form that speaks more directly of Christianity. I certainly think this approach has its place (when done with discernment). However, it is clear that this Christian art form with no Chinese connection at all, and which originated in Western Europe in the middle ages, spoke powerfully and eloquently to this Chinese lady.

While I do think that there are geographic and time-bound elements that characterize all aspects of the culture, I have never been of the view that these are the only influences. Christian culture reflects also the Faith, which is universal - that is, it is true for all people. So I would say that traditional Western European culture, for example, looks as it does because it is Christian and to a large degree would have looked the same if it had originated in the southern tip of Africa. This being so and to the degree that any art form is Christian, it will speak to people in all ages and places. This means, therefore, that exporting Western European culture (or Christian Eastern European culture, Christian Middle Eastern culture for that matter) to the rest of the world is not cultural imperialism as some might suggest. Nobody forced Yan down this route, she was attracted by it and chose to follow. She is responding to a gift, freely given. It is called evangelization!

Baroque Landscape: Chinese Baroque!

This is another in the series about baroque landscape…and its not about baroque landscape, but bear with me. It is relevant to the topic. I am fascinated by the beauty of Chinese landscape. Once I started to learn about the baroque style I noticed that the same basic features are present in the form of Chinese art too. Further investigation revealed that the traditional Doaist understanding of the natural world and man’s relation to it, as manifested in Chinese art, are in accord in many ways with the Catholic worldview.

Considering form first: if we look at any of the paintings shown here we see these features. There are a limited number of principle foci of interest which are more detailed and more coloured. The areas in between these are muted in colour and rendered in monochrome, usually black and grey ink washes.

In fact in Chinese painting the contrast in the treatment of the focal points and background areas is even more pronounced. The areas between the foci are often no more than a hazy mist. However, there is always a unity to the painting. It looks like a single scene not painting containing three unconnected scenes.

This is another in the series about baroque landscape…and its not about baroque landscape, but bear with me. It is relevant to the topic. I am fascinated by the beauty of Chinese landscape. Once I started to learn about the baroque style I noticed that the same basic features are present in the form of Chinese art too. Further investigation revealed that the traditional Doaist understanding of the natural world and man’s relation to it, as manifested in Chinese art, are in accord in many ways with the Catholic worldview.

Considering form first: if we look at any of the paintings shown here we see these features. There are a limited number of principle foci of interest which are more detailed and more coloured. The areas in between these are muted in colour and rendered in monochrome, usually black and grey ink washes.

In fact in Chinese painting the contrast in the treatment of the focal points and background areas is even more pronounced. The areas between the foci are often no more than a hazy mist. However, there is always a unity to the painting. It looks like a single scene not painting containing three unconnected scenes.

I began to investigate a bit and read a book called The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting. This was written in China in the 1600s (which, coincidentally, is the baroque period in the West). What struck me is that their understanding of the natural world and how man relates to it is in accordance with the Christian worldview. The Daoist worldview does not include God, but it does recognize heaven, a place that is non-material. The natural world reflects a heavenly order and the task of man and his work is to act in harmony with it. Therefore, just like the Christian painters of the same period, they saw the beauty of the natural world as something that pointed to a place beyond it that was non-material. When we apprehend the beauty of nature, we perceive intuitively the harmonious relationships that exist between the parts; and the harmonious relationship of the whole to God (for the Christian), and to heaven (for the Daoist). As a Catholic I say that all harmony is derived from the harmonious relationships that are intrinsic to God, between the persons of the Trinity.

Compare, for example, two quotes that follow. The first by St Thomas Aquinas and the second by the Chinese sage, Lao Tzu:

‘The order of the parts of the universe to each other exists in virtue of the order of the whole universe to God’ St Thomas Aquinas (Questiones disputatae de veritate, 7,9)

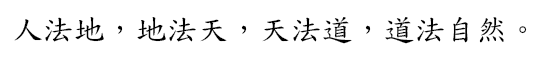

‘Man’s standards are conditioned by those of Earth, the standard of Earth by those of Heaven, the standard of Heaven by that of the Way [Tao] and the standard of the Way is that of its own intrinsic nature.’ Lao Tzu, (from Tao Te Ching, XXV, 6th century BC)

It seems strange to me, that with their view of an ‘empty’ heaven they did not, historically at least, welcome the revelation of a God. It is though they had already deduced the existence of heaven but with an empty throne, and Christianity could provide the only King who is worthy to sit on it. Christ even told us that he is ‘the Way’ (John 14:6)

It seems strange to me, that with their view of an ‘empty’ heaven they did not, historically at least, welcome the revelation of a God. It is though they had already deduced the existence of heaven but with an empty throne, and Christianity could provide the only King who is worthy to sit on it. Christ even told us that he is ‘the Way’ (John 14:6)

So, coming back to painting, when they painted a landscape they sought to capture its beauty by mimicking the way that man observes nature. Again, this is just like the baroque method.

The landscape tradition is much older in the China than in Europe, and I would say that this representation of the balance between the particular and the whole was at a much more mature in Chinese art than in the baroque landscapes of this period. Part of the training of any artist should be the study of the work of Masters in their tradition. Any artist wishing to specialize in landscape could benefit from the study of Chinese landscapes, I suggest, even if the ultimate aim is a Western form.

This has happened in the past. There has always been an easy crossover between Chinese and Western naturalistic landscape painting. Nineteenth century French landscape artists, especially the Impressionists, were fascinated by Chinese and Japanese landscape and incorporated many compositional elements into their own work.

It works the other way too. To demonstrate the point, I should now come clean and explain that not all the paintings in this article were painted by a traditional Chinese artist. The second is, but the first and third are by a classically trained Italian artist, who was also a Jesuit missionary to China in the mid-eighteenth century, called Giuseppe Castiglione. He was admired in China for his work and was patronized by the Emperor. I first came across his work at an exhibition at the Royal Academy a couple of years ago.

The first painting below is by Castiglione again. The others are by a contemporary artist, Henry Wo Yue-Kee, based in Alexandria, Virginia. He was sitting in a shop front working one day when I walked past and noticed him. He told me that he had moved here from Hong Kong where he was trained.

I found this link through to short description of Castiglione's life and 40 images of his work (as reproduced on the stamps of China, Taiwan and Korea!)

How a Search for High Quality Painting Brushes Created Chinese Characters that Communicate the Gospel

Here's an unusual story. First of all a tip for anyone looking for brushes for icon painting. I was looking for a source for good cheap brushes to use with egg tempera. The usual recommendation is Kalinsky sable. These are very expensive watercolour brushes and made from sable hair (a sable is an animal, a Russian marten). If you use brushes for watercolour they will last a lifetime, but if you use them for egg tempera they quickly degrade because the paint is quite abrasive, made from pigment - which is effectively coloured grit - and egg yolk, diluted with water. This can become expensive quite quickly. Luckily, I discovered that Chinese painting brushes are an excellent but much cheaper alternative. They are made to come to a point for use with calligraphy and hold a large amount of paint, so are perfect for painting in egg tempera. I get my brushes from an online supplier called Good Characters, here.

Another side of their business is doing a consultancy for people doing business in China - they develop company logos that will speak to the Chinese and give the right impression. As a regular customer, and as part of a promotion for this Andy Chuang who runs the company in California asked me if I wanted him to create a Chinese character for me. I thought about it and suggested this:

Here's an unusual story. First of all a tip for anyone looking for brushes for icon painting. I was looking for a source for good cheap brushes to use with egg tempera. The usual recommendation is Kalinsky sable. These are very expensive watercolour brushes and made from sable hair (a sable is an animal, a Russian marten). If you use brushes for watercolour they will last a lifetime, but if you use them for egg tempera they quickly degrade because the paint is quite abrasive, made from pigment - which is effectively coloured grit - and egg yolk, diluted with water. This can become expensive quite quickly. Luckily, I discovered that Chinese painting brushes are an excellent but much cheaper alternative. They are made to come to a point for use with calligraphy and hold a large amount of paint, so are perfect for painting in egg tempera. I get my brushes from an online supplier called Good Characters, here.

Another side of their business is doing a consultancy for people doing business in China - they develop company logos that will speak to the Chinese and give the right impression. As a regular customer, and as part of a promotion for this Andy Chuang who runs the company in California asked me if I wanted him to create a Chinese character for me. I thought about it and suggested this:

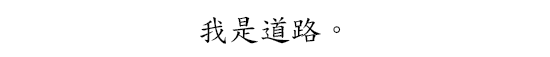

First of all the statement from Lao Tsu: ‘Man’s standards are conditioned by those of Earth, the standard of Earth by those of Heaven, the standard of Heaven by that of the Way [Tao] and the standard of the Way is that of its own intrinsic nature.’ (from Tao Te Ching, XXV (6th century BC)

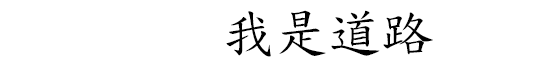

Then I asked that this be juxtaposed with the scriptural quote: ‘I am the Way’ Jesus Christ, (John 14:6)

I thought maybe it would help evangelise China. Doaism has belief in heaven which is a non-material, spiritual place, but is an impersonal, empty heaven with no God. I thought that maybe putting these together might lead them to accept Christ as the fullness of what is believed.

Andy was very happy to oblige and sent me the following. First the Lao Tsu

and then from John's gospel

then he sent me a Chinese screen image into which I could insert them. My techie skills aren't up to it but I thought I would show it in case any readers want to make use of it.

Then he gave me the same script but in a more artistic arrangement of the letters:

and from the gospel:

So I encourage readers to share these to things together and spread the gospel in China. For once we wouldn't mind if Beijing was hacking this site!

Chinese Landscapes in Berkeley, CA

I spent Easter Week in Berkeley, CA recently and so as I always try to do when visiting a town I went to visit the local art gallery. It is amazing what treasures even a local gallery can have sometimes. Berkeley is the home of hippies and is where the Sixties began, so I was ready also for plenty of whacky stuff. However, it is also the gallery of one of the most famous and wealthiest universities in the US which was founded well before this so hoped for at least something good. The website even mentioned that there was a Rubens in the collection.

I spent Easter Week in Berkeley, CA recently and so as I always try to do when visiting a town I went to visit the local art gallery. It is amazing what treasures even a local gallery can have sometimes. Berkeley is the home of hippies and is where the Sixties began, so I was ready also for plenty of whacky stuff. However, it is also the gallery of one of the most famous and wealthiest universities in the US which was founded well before this so hoped for at least something good. The website even mentioned that there was a Rubens in the collection.

It didn't look to hopeful when we approached the gallery and the exterior looked like this...

There are some buildings that, like a pearl inside the oyster shell have beautiful interiors despite their exteriors. This wasn't one of them. It was bare concrete on the outside and bare concrete on the inside. It really could have done with a few good pictures to spruce it up a bit. However, what we were presented with, for the most part, managed against all odds to make it even worse. The whole gallery was given over to an exhibition called 'Silence' which was based upon John Cage's 1950s composition 4'33''. For those who don't know this is a 'composition' in which the musicians sit in front of a blank score for this period of time and follow the instructions to do nothing, ie sit in silence.

As we progressed, it didn't look too hopeful. For example there was I mime artist lying on the ground rolling around in slow motion. It wasn't even interesting enough to affront. Not wanting to cause offence I just quietly walked past as though I hadn't noticed he was there. Most of the rest of stuff is the sort of avant garde modernist stuff that I used to pretend to be interested in order to look arty. Isn't all of this past it's sell by date yet? The was some traditional art - this being the Bay Area lots of Buddhist art. I don't remember any explicitly Christian art of course - they are liberal, but not that liberal.

I was just beginning to wonder if the curator might have been better advised to have followed John Cage's example and present us with a series of empty rooms, when I turned the corner and saw a room of traditional Chinese landscapes on screens.

The monochrome landscapes are worthy of study even by those who wish to work in the Western tradition. The skill in varying the focus, having some areas clearly defined and others hazy, yet maintaining a unified image is great.

What was interesting to me also was the fact that the reverse side of the big screen shown above had a geometric pattern on it, which could have come straight from a Romanesque tiles floor.

So while I can't say that the exhibition is worth travelling a long way to see, these examples made it worthwhile crossing the town.

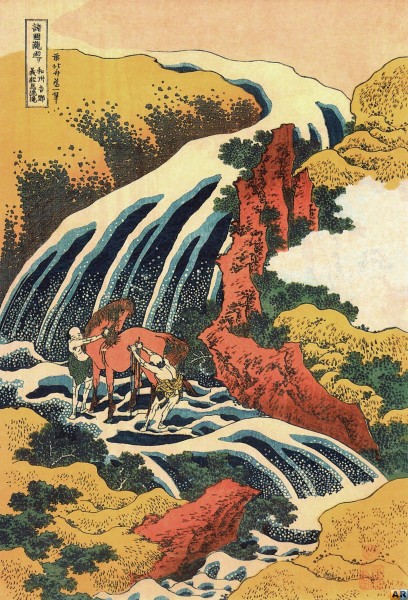

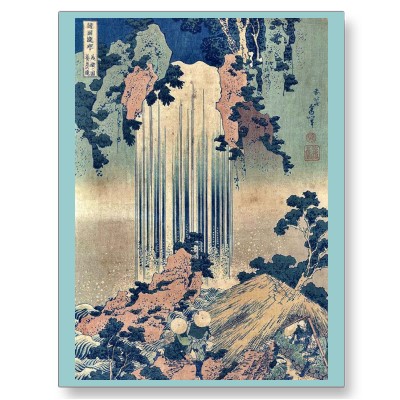

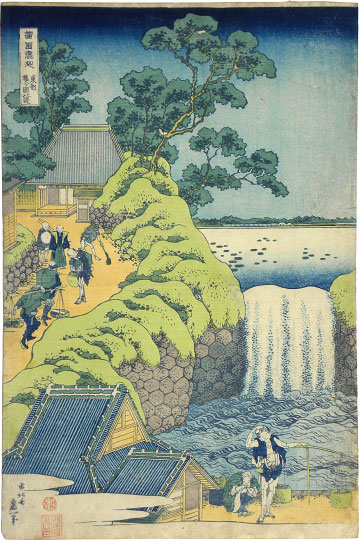

19th Century Japanese Landscapes from Worcester Art Museum

Here is a series of 18th century prints by the Japanese artist called Katsushika Hokusai(1760-1849). I saw them recently as a new display at the permanent collection of the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. Chinese and Japanese landscape is worthy of study even by those interested in painting landscape in the Western tradition. The composition is consistent with the Christian view that nature is beautiful and hierarchical and points to something greater beyond itself, with man at the pinnacle of the natural world, whether he is a subject within the painting, or the observer seeing nature through the eyes of the artist.

This is a series of prints called A Tour of Waterfalls in the Provinces made in 1833. This is a new display at the Worcester Art Museum and it has been very nicely handled, so that the series appears as a body of work, with each print angled upwards so that it is easily visible and reducing glare of the protective glass.

Here is a series of 18th century prints by the Japanese artist called Katsushika Hokusai(1760-1849). I saw them recently as a new display at the permanent collection of the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. Chinese and Japanese landscape is worthy of study even by those interested in painting landscape in the Western tradition. The composition is consistent with the Christian view that nature is beautiful and hierarchical and points to something greater beyond itself, with man at the pinnacle of the natural world, whether he is a subject within the painting, or the observer seeing nature through the eyes of the artist.

This is a series of prints called A Tour of Waterfalls in the Provinces made in 1833. This is a new display at the Worcester Art Museum and it has been very nicely handled, so that the series appears as a body of work, with each print angled upwards so that it is easily visible and reducing glare of the protective glass.

Worcester Art Museum is one of a number of small museums based upon the private collection of wealthy industrialist, now available to the public. It is small enough that one can easily see all on display in its three floors of galleries in a morning and good enough that one wants to. it also saves the parking and travelling difficulties of trying to get to galleries in the centre of large cities. We will feature more works from this gallery in a number of upcoming posts.

Japanese Sacred Art

Changing Appearances According to the Audience

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics (handed down to us by tradition); but at the same time the artist will always consider modifying the appearance so that those who are likely to see the painting will identify with Him or her. Here are some paintings by Chinese Christians. The first, left, dates from the 14th century and the second from the turn of the last century.

Christ is the Everyman, the model for all humanity. When He (or indeed Our Lady and the saints) are painted, the image must also participate in a model of humanity that the audience can relate to. All sacred art is a balance of the general and the particular. If those who are going to see the painting are going to be almost exclusively Chinese, then it is a legitimate approach, I would argue, to portray Christ and Our Lady as Chinese.

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics (handed down to us by tradition); but at the same time the artist will always consider modifying the appearance so that those who are likely to see the painting will identify with Him or her. Here are some paintings by Chinese Christians. The first, left, dates from the 14th century and the second from the turn of the last century.

Christ is the Everyman, the model for all humanity. When He (or indeed Our Lady and the saints) are painted, the image must also participate in a model of humanity that the audience can relate to. All sacred art is a balance of the general and the particular. If those who are going to see the painting are going to be almost exclusively Chinese, then it is a legitimate approach, I would argue, to portray Christ and Our Lady as Chinese.

This principle is used famously, in a different way, in the Isenheim altarpiece painted in the early 16th century in the gothic style by the German artist Matthias Grunewald. Christ is horribly disfigured, but not as he would have been disfigured by the passion. This painting was made for a hospital in which people were suffering from an illness caused by fungus in the rye grain used in the bread eaten locally. The cause was not known at the time and so the illness was incurable. The symptoms match exactly those that Christ has in the painting. This is clearly intended to offer solace to the patients to communicate to them that Christ is suffering with them and for them.

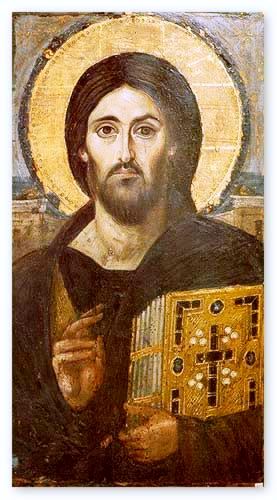

There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

Even if my suggestion is correct. It doesn’t apply universally. The last two are from Russia. So in this case the skin tone reflects neither the uncreated light, nor that of those who are likely to see the icon. I once had lessons from an icon painter in England who had been at one time a student of the famous Russian iconographer, Ouspensky. She told me to use predominantly the green-brown colour that we see there (called ‘avana ochre’) with highlights used sparingly in yellow ochre and white specifically because it matched the olive-brown Mediterranean complexion.

It seems that an artist has a choice in these matters. The governing principle is that he should aim to maximize his chances of communicating the person of Christ to those who are likely to see his work.

Caravaggio's Flagellation of Christ

Caravaggio's Flagellation of Christ

Japanese Landscape

The compatibility of traditional Japanese and Western Landscape I have discussed before the compatibility of Chinese and baroque landscape. The controlled variation in focus and colour is common to Eastern and Western forms - the most important parts of the composition in sharper focus and, if it is not monochrome, most intensely coloured. Traditional Japanese landscape is worthy of study too. If anything the variation is even more marked. So much so that I would suggest that any budding landscape artist study these as part of their training, even if eventually they wish to concentrate on the Western form. One of the hardest things to do when painting from nature is to decide which parts are blurred and which in focus so that the end result is a coherent, unified impression. I feel that study of these Eastern forms would help develop this faculty.

The compatibility of traditional Japanese and Western Landscape I have discussed before the compatibility of Chinese and baroque landscape. The controlled variation in focus and colour is common to Eastern and Western forms - the most important parts of the composition in sharper focus and, if it is not monochrome, most intensely coloured. Traditional Japanese landscape is worthy of study too. If anything the variation is even more marked. So much so that I would suggest that any budding landscape artist study these as part of their training, even if eventually they wish to concentrate on the Western form. One of the hardest things to do when painting from nature is to decide which parts are blurred and which in focus so that the end result is a coherent, unified impression. I feel that study of these Eastern forms would help develop this faculty.

This is not a new idea. The landscape painters of the 19th century, such as the Impressionists and others such as the great John Singer Sargent studied Japanese art (especially woodcut prints) and their compositional style was affected by it. If we look at the painting at the bottom by Alfred Sisley, (who came from and English family, but lived in France) example, the hanging boughs that frame the composition and the indication of branches and foliage in the very near foreground is a development in the 19th century that corresponds to the Eastern style of composition.

Other articles describing the principles of baroque landscape here.