I have been invited by the OQ Farm in beautiful farmland close to Woodstock, Vermont) to lead a weekend retreat centered around the traditional formation that would been given to the great Catholic artists of the past. This will certainly be of interest to artists of any creative discipline; but not just artists. It is open to anyone seeking a traditional formation in beauty and inculturation that engenders creativity and openness to inspiration. It takes place from the 3-5th June, 2016.

I have been invited by the OQ Farm in beautiful farmland close to Woodstock, Vermont) to lead a weekend retreat centered around the traditional formation that would been given to the great Catholic artists of the past. This will certainly be of interest to artists of any creative discipline; but not just artists. It is open to anyone seeking a traditional formation in beauty and inculturation that engenders creativity and openness to inspiration. It takes place from the 3-5th June, 2016.

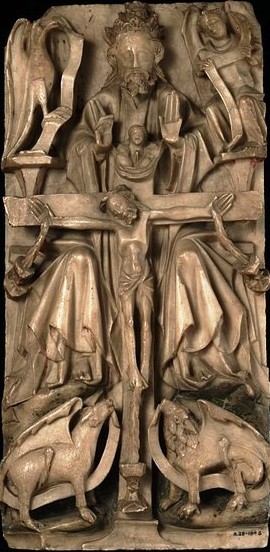

John Paul II said in his Letter to Artists, written in 1999, that every person has a personal vocation to contribute creatively and beautifully to the culture in some way as we go about our daily lives. In that sense we might become artists through supernatural means: by being united to Christ we are transformed and participate in the divine nature. St Athanasius was referring to this supernatural transformation in the 3rd century AD when he said that, 'God became man, so that we might become god'. Maximus the Confessor, in the 7th century AD, in reiterating this said that, 'One becomes all that God is, except an identity in being, when one is deified by grace.' Benedict XVI said that through this each of us can participate in the 'creative love of God'.

It is an extraordinary privilege, yet it is one that is offered through the Church to every single person.

This call to be raised up so that God works through us, and to contribute creatively and beautifully to society, is the essence of the New Evangelization. Through grace we lead a life of beauty and contribute creatively to a new culture. It is by this beauty and love in our lives that others see Christ and are drawn to the Faith. This result is described by Benedict in his paper on the New Evangelization, written in 2001; and in the same paper he gives us the method by which we can participate in this. The method of the 'New' evangelization is rooted in the one which worked so successfully for the early Church. It is a traditional pattern of prayer, which incorporates different sorts of prayer and contemplation, and has the worship of God in the sacred liturgy at its heart. This will be a journey in which together we will study this short document (under 10 pages) and try to put into practice what he describes.

This call to be raised up so that God works through us, and to contribute creatively and beautifully to society, is the essence of the New Evangelization. Through grace we lead a life of beauty and contribute creatively to a new culture. It is by this beauty and love in our lives that others see Christ and are drawn to the Faith. This result is described by Benedict in his paper on the New Evangelization, written in 2001; and in the same paper he gives us the method by which we can participate in this. The method of the 'New' evangelization is rooted in the one which worked so successfully for the early Church. It is a traditional pattern of prayer, which incorporates different sorts of prayer and contemplation, and has the worship of God in the sacred liturgy at its heart. This will be a journey in which together we will study this short document (under 10 pages) and try to put into practice what he describes.

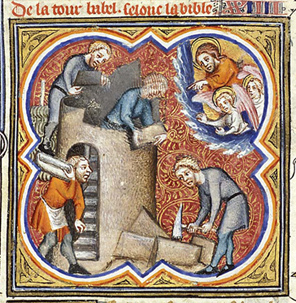

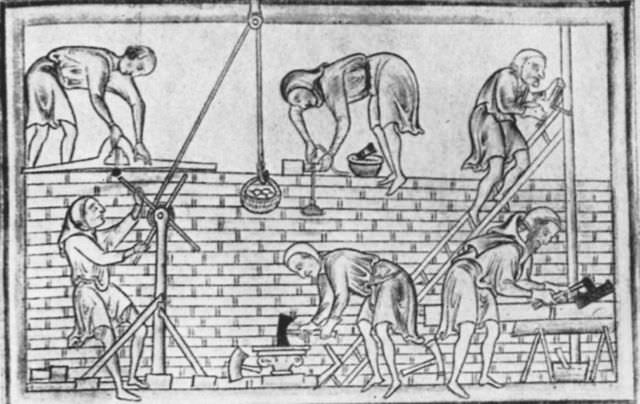

This is what formed the great evangelists of the past; and it also what enabled so many of the great painters of the past to create beauty for the greater glory of God. In many ways it is building on what was described in the book written by Leila Lawler and myself, the Little Oratory - A Beginner's Guide to Praying the Home. In this weekend we will go more deeply into the subject, learning more about how the beauty of the Catholic traditions of sacred art (as specified by Benedict XVI in his book the Spirit of the Liturgy), through form and content support the prayer life and the themes that he highlights in his paper on the New Evangelization. We will experience the methods he describes first hand the prayer that it describes, with additional insights.

As such it is a mini Catholic inculturation that you can benefit from and take with you to your domestic church. In fact the hope of this weekend is that what you get will not stop when you leave. Prayer at home, as well as in our parish church, is a vital component to what Benedict describes. Benedict told a synod on the family in 2008 that, 'The new evangelization depends largely on the Domestic Church. The Christian Family to the extent it succeeds in living love as communion and service as a reciprocal gift open to all, as a journey of permanent conversion supported by the grace of God, reflects the splendor of Christ in the world and the beauty of the divine Trinity.’ The point should be made here that this does not only apply to families, it is true for and open to everyone, no matter what their state in life. We all have a home, and so we can all create a domestic church! It is how we turn a house into a home.

In the beautiful and peaceful surroundings of rural Vermont you will:

- Learn to pray the Divine Office in English using traditional chant, so that you can do it at home or parish (no previous music training necessary)

- Learn to engage with visual imagery in your prayer - in the liturgy and in devotional and contemplative prayer (conspectio divina).

- Learn how to choose images, based upon traditional principle, for your own domestic church that will promote this supernatural transformation.

- Understand why the great figurative traditions of the sacred art of the Church are formed so as to engender such a transformation, both through the content - what they portray; and style - how they portray it.

OPTIONS:

Weekend Retreat Package: $375 per person

Arrive on Friday, 6/3 by dinner, depart by noon on Sunday, 6/5

Includes semi-private lodging and all weekend meals. A limited number of private rooms are available for an additional cost. Please see Lodging,Travel and Meals (link) for more information.

Saturday Commuter Package: $125 per person

Arrive by 8am Saturday, joining for all daytime activities and shared lunch -- departing before dinner

To book, and for more information please contact the Director of Arts Initiatives, Keri Wiederspahn: keri@oqfarm.org; 802.230.7779 or got to http://www.oqfarm.org/workshops-overview/

Below a beautiful icon of the transfiguration, painted by monks at Mt St Angel Abbey, Oregon. This is a painting of the event that anticipated Christ in glory in heaven. It is also a painting of the mystical body of Christ, the Church. When we are transformed, in Christ, in this life, we can be a pixel of light in his body, drawing people to the Faith.

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 ( If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy. Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us? Mark the Hours

Mark the Hours So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication  The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.