"Geometric pattern is the abstract art of Christianity."

We tend to think of abstract as something that has come about only within the last one hundred years. But liturgical artists have had their own form of abstract art for nearly two thousand years. Geometric pattern is the abstract art of Christianity.

God made all of creation, visible and invisible, to teach us about Himself. When we perceive the order and pattern that is inherent in creation, the numbers that underlie all of creation, we see the thumbprint of God.

Geometrical forms, built up from mathematical (numerical) forms, are a symbolic expression of Christian Truth. They represent the thoughts of God.

In the Christian world, numbers have both a quantitative meaning and a qualitative meaning. They tell us the amount of some thing (quantity) but they also tell us about the thing itself. (qualitative.)

A carton of a dozen eggs, for example, holds a quantity of 12 eggs. But the number 12 also has a symbolic meaning. it may represent the 12 tribes of Israel, the 12 apostles, 12 signs of the zodiac, or 12 months of the year. Which of these symbols the number represents will depend on the context in which it is used.

In the context of a work of sacred art, depending on the other elements of the work, 12 eggs could represent the New Covenant, a new Church emerging from the "sealed tomb" of the old Law, resting on the foundation of the twelve apostles.

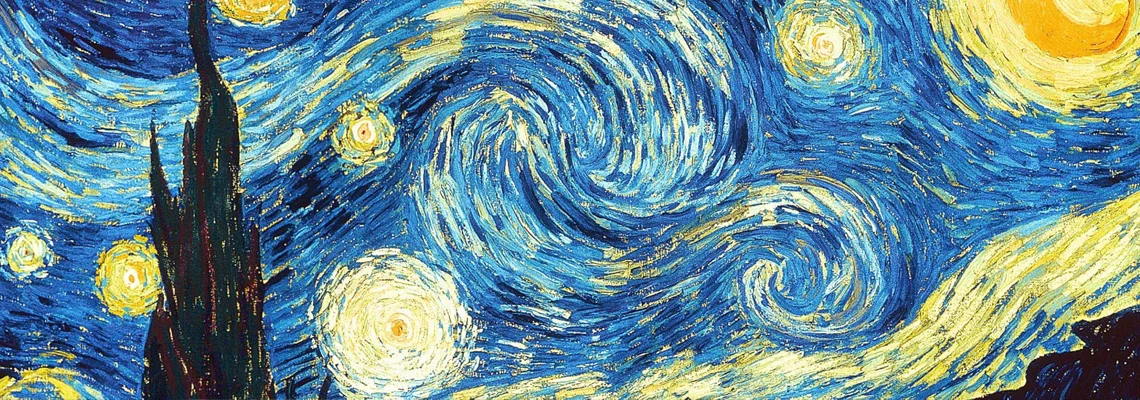

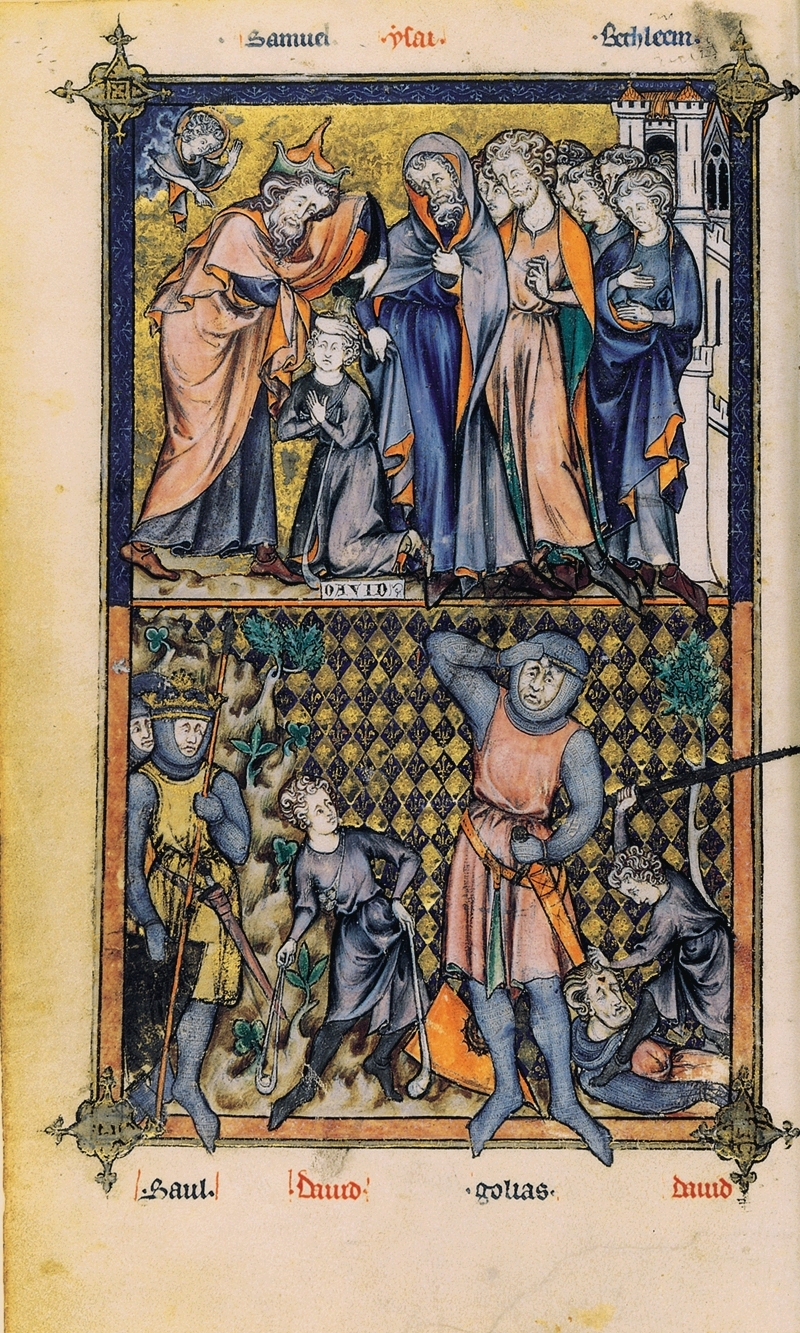

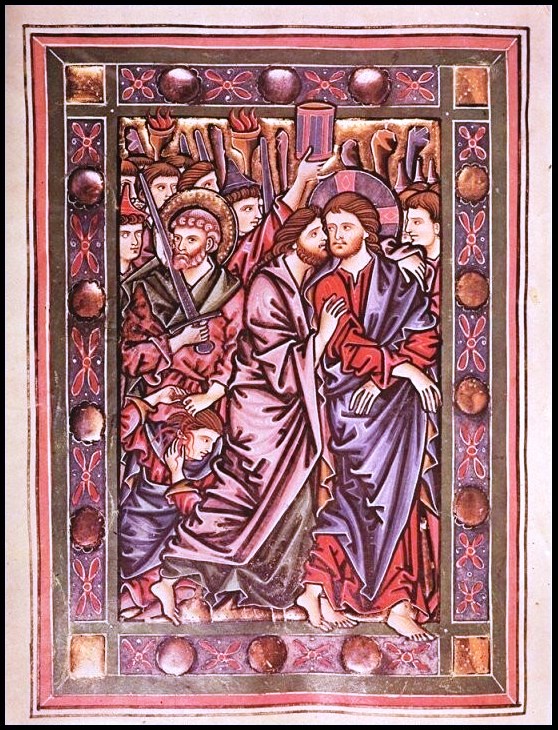

But this qualitative and quantitative language of numbers can also be used to construct abstract, i.e. non-representational, patterns that can lead us to contemplate heavenly things. Medieval manuscript paintings often have a geometric pattern serving as the background as a symbol of the order of heaven.

The work above is a design for a church floor, completed as part of the Masters of Sacred arts program at Pontifex University. It incorporates a specific type of scrolling pattern known as a guilloche. This is a meditation on Christ in the form of a geometric pattern.

Down the middle axis of the design are three shapes. The first shape at the top contains the symbol for "alpha," the first letter of the Greek Alphabet, The bottom shape holds the symbol for "omega," the last letter. Alpha and omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end, come together in the middle in a "Christogram" a symbol representing Christ. Jesus Christ is the alpha and the omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end. Christ is the mediator between man and God. In the ancient world, the number "2" was a mediator between the numbers 1 and 3. The number "2" then, represented a mediation between two extremes, heaven and earth, divine and human, God and man. We might also say then that Jesus, the second person of the Holy Trinity, mediates between God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

Flowing around these central shapes is a bough of laurel leaves in a guilloche pattern. Laurel leaves are a symbol of victory, Christ is victorious over sin and death. The laurel bough weaves around eight medallions which contain another type of Christogram, in this case a cross and the letters INRI. They serve to remind us that Christ obtained His victory through death on a cross, a death at which He was proclaimed Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

And "eight" medallions also have a hidden meaning. Eight is the number of the victorious resurrected Christ and a redeemed world. Eight is the sum of "7" the number of totality and completion, and the number "1," representing the singularity of God. The number "8" is used in baptismal fonts as a symbol of a new life brought from darkness into light.

The victorious Christ is the eight day, heralding a new birth and a new creation. He brings the world from darkness into light.

There is no reason we cannot imbue the design of our churches with such geometric patterns and symbols that hold a rich symbolic language revealing the truths of the invisible world that are hidden within the visible. All it takes is the knowledge, and the will.

this article originally appeared at www.DeaconLawrence.org

______________________________________

Pontifex University is an online university offering a Master’s Degree in Sacred Arts. For more information visit the website at www.pontifex.university

Lawrence Klimecki is a deacon in the Diocese of Sacramento. He is a public speaker, writer, and artist, reflecting on the intersection of art and faith and the spiritual “hero’s journey” that is part of every person’s life. He maintains a blog at www.DeaconLawrence.org