It was through my work for the lonely, the addicted, the abused and neglected, for the sick and suffering—whether that be in Haiti, Nicaragua, rural America or the classrooms of the Ivy League—that I learned the wisdom of Benedict XVI’s Mariology as an antidote to a pride-filled activism.

A Rosary Walk For Our Times. A Brilliant Sculpture by Thomas Marsh

Sassoferrato's Virgin at Prayer - for the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

For today's Feast of the Birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary here is the Virgin at Prayer by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato who is generally known simply as Sassoferrato. He lived from 1609 to 1685.

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century. The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was later fixed at December 8, nine months prior.

For today's Feast of the Birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary here is the Virgin at Prayer by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato who is generally known simply as Sassoferrato. He lived from 1609 to 1685.

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century. The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was later fixed at December 8, nine months prior.

There is a commentary on the Feast from the following information is drawn, here, by Fr Matthew Mauriello: 'The primary theme portrayed in the liturgical celebration of this feast day is that the world had been in the darkness of sin and with the arrival of Mary begins a glimmer of light. That light which appears at Mary's holy birth preannounces the arrival of Christ, the Light of the World. Her birth is the beginning of a better world: "Origo mundi melioris." The antiphon for the Canticle of Zechariah at Morning Prayer expressed these sentiments in the following way: "Your birth, O Virgin Mother of God, proclaims joy to the whole world, for from you arose the glorious Sun of Justice, Christ our God; He freed us from the age-old curse and filled us with holiness; he destroyed death and gave us eternal life.

'The second reading of the Office of Readings is taken from one of the four sermons written by St. Andrew of Crete ( 660-740 ) on Mary's Nativity. He too used the image of light: "...This radiant and manifest coming of God to men needed a joyful prelude to introduce the great gift of salvation to us...Darkness yields before the coming of light."

This painting, like the painting of Gregory the Great by Vignali, described last week, is in the baroque style of the 17th century. Again, we see the sharp contrast between light and dark symbolizing the Light overcoming the darkness, and again like the Vignali, the face is in partial shadow ensuring that this is distinct in style from a portrait (I described the reasons behind this in more detail in the earlier posting). There is an additional element here in the portrayal of the face that was not so strongly present in Vignali's painting. The facial features are highly idealized and bear the likeness of the ancient Greek classical ideal.

Sassoferrato's training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael's faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal and this was picked up by the Caraccis in the late 16th century (most famously Annibale) who founded a school from which most of line of influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

Sassoferrato's training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael's faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal and this was picked up by the Caraccis in the late 16th century (most famously Annibale) who founded a school from which most of line of influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

All Christian sacred art must have a balance of idealism, which points to what we might become; and naturalism which roots the image in the particular and what we see and know in the here and now. The different styles of Christian sacred art look different from each other because they look to different sources for their ideal, and because of the exact balance of idealism and naturalism they reflect. Baroque classicism is called so to distinguish it from 'baroque naturalism' in which, though still partially idealized in accordance with what is good for Christian sacred art, has a greater emphasis on natural appearances. Ribera would be an example of the naturalistic school and Poussin was one of the most famous proponents of baroque classicism.

We can see the similarities in the facial features of the Sassoferrato Virgin, Raphael's Alba Madonna (which I describe in more detail in a posting here) and the ancient Greek statue the Venus of Arles from the Louvre. This strong idealization is another way that the artist ensures that portrayal of Our Lady is a piece of sacred art and avoids it looking like a portrait of the girl from next door dressed in historical costume.

Here is the Venus of Arles:

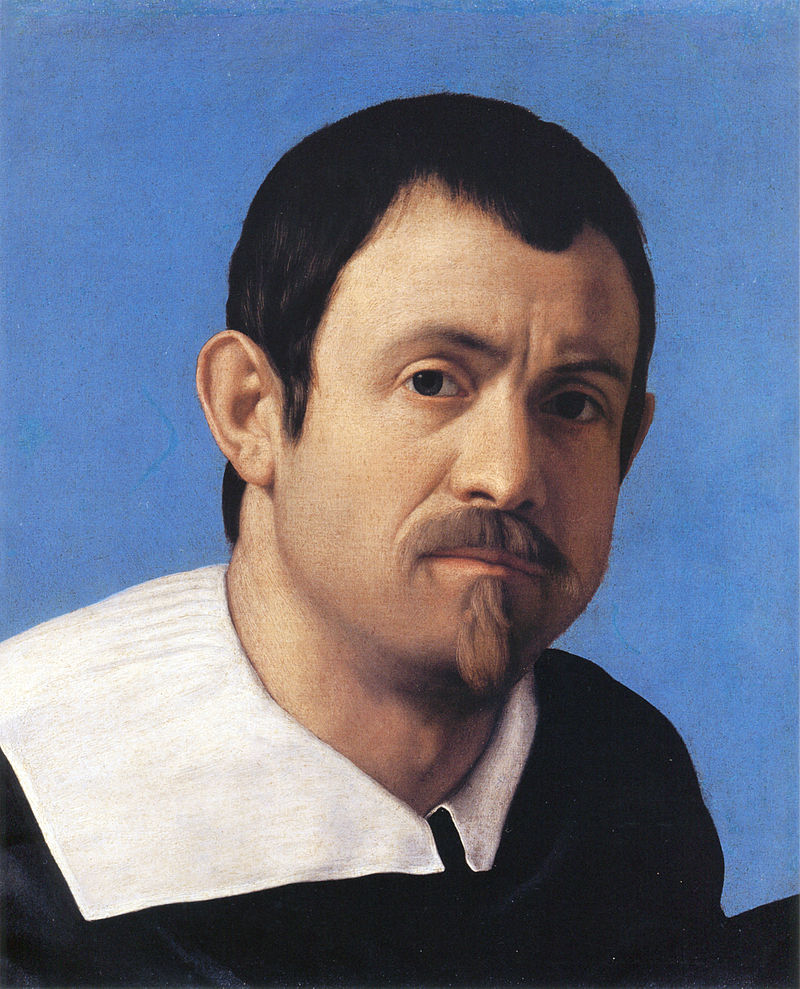

We can see the difference between the way in which sacred art and mundane art are painted by contrasting what these works with Sassoferrato's self portrait. Notice how in the portrait the image engages the viewer much more directly and we look deeply into his eyes, the deep shadow is absent and background is blue rather than black so the contrast between light and dark is not so pronounced. There is still some shadow in the face certainly - this necessary in order to describe form - but it is not so marked. Also there is not such an obvious fusion of the natural features of the face with those of the Greek ideal as we would see in the sacred art.

Sassoferrato's Virgin is in the National Gallery in London and I have a great fondness for it, even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery. As a gallery that has no entrance fee, I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

Sassoferrato's Virgin is in the National Gallery in London and I have a great fondness for it, even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery. As a gallery that has no entrance fee, I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

— ♦—

My book the Way of Beauty is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School of the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”

The Pictorial Symbol of a Virgin Before, During and After Giving Birth

One of the tasks that those who are interested in cultural renewal have to face today is one of reawakening to the symbolism of the cosmos. This faculty can be stimulated, I believe, by incorporating a language of symbolism into art. I have written before of how when painting today, the artist has to decide on a case by case basis which symbols to revive and which to ignore (see Pelican Brief - Should We Aim to Revive All Christian Symbols of Sacred Art). A symbol must speak to those who are meant to see it and some symbols are so rooted in a culture that is bound to a different time and place that it is unlikely ever to communicate much to any nowadays but learned art historians.

The symbols that seem most prevelant and useful are those that are based on scripture or tradition and furthermore speak naturally of what they are trying to convey. These are the ones that I tend to focus on. So while the halo represents the uncreated light of sanctity it is not an arbitary symbol. It is as much a stylised representation of light eminating from the person.

One of the tasks that those who are interested in cultural renewal have to face today is one of reawakening to the symbolism of the cosmos. This faculty can be stimulated, I believe, by incorporating a language of symbolism into art. I have written before of how when painting today, the artist has to decide on a case by case basis which symbols to revive and which to ignore (see Pelican Brief - Should We Aim to Revive All Christian Symbols of Sacred Art). A symbol must speak to those who are meant to see it and some symbols are so rooted in a culture that is bound to a different time and place that it is unlikely ever to communicate much to any nowadays but learned art historians.

The symbols that seem most prevelant and useful are those that are based on scripture or tradition and furthermore speak naturally of what they are trying to convey. These are the ones that I tend to focus on. So while the halo represents the uncreated light of sanctity it is not an arbitary symbol. It is as much a stylised representation of light eminating from the person.

In contrast colour symbolism is more arbitrary. In fact no strict colour code of symbolism for any of the liturgical traditions, including even iconography (perhaps surprisingly). That is not to say that artists have not chosen colours in order convey spiritual meanings, and temporary trends can develop when artists are influenced by others in their choice. However, it is very difficult to find any colour symbolism that is observed consistently either across different traditions or even within one.

Occasionally I am presented with a colour symbolism as though it is a strict rule. Usually, however, on digging more deeply I discover that over the ages all sorts of different colours have been used; or even where there is a conformity to a colour, the explanation of the symbolism differs, which causes me to wonder to wonder if these are not just explanations after the fact which are not rooted in tradition. The Church Fathers it seems are silent on such matters (although as ever, I am happy to told otherwise and directed to writings I haven't seen yet).

Occasionally I am presented with a colour symbolism as though it is a strict rule. Usually, however, on digging more deeply I discover that over the ages all sorts of different colours have been used; or even where there is a conformity to a colour, the explanation of the symbolism differs, which causes me to wonder to wonder if these are not just explanations after the fact which are not rooted in tradition. The Church Fathers it seems are silent on such matters (although as ever, I am happy to told otherwise and directed to writings I haven't seen yet).

There is one symbol that I am inclined to employ even though I do not know why it has come to symbolise what it does. This is the placement of three stars on the garment of Our Lady that is used in icons - one on each shoulder of her outer robe and one on the forehead. Someone asked me recently what they meant and I knew that it represented perpetual virginity, but couldn't remember why. As was quickly pointed out to me, they correspond to the idea that Our Lady was a virgin before, during and after birth. However, I still have no idea why three stars are used to symbolise this. Our Lady is often associated with the North Star, the Star of the Sea, and so I wondered if it was somehow evoking this. As often happens to, the very next day, there was a reference to this in the liturgy. The reading for the Feast of Saints Anne and Joachim was from John of Damascus and in this he says to Our Lord's grandparents, that : 'By your pure and holy way of life you brought up that jewell of virginity, she who before giving birth was a virgin, who while giving birth was a virgin, and who after giving birth was ever a virgin; yes, she who was always unique, who was to cherish virginity in mind, in spirit and also in body.' So I'm unlikely to forget that again...except there is no direct connection with a star and perhaps taking our lead from St John of Damascus, the three stars might represent a 'cherished virginity' that encompasses the whole person - mind, spirit and body - as well as in perpetuity?

Can anyone help me here?

The reason that I am inclined to use this is that it does seem to be well established across all the differing iconographic traditions. And it is an important message to get across. Furthermore, I can't think of a more natural or appropriate way of symbolising this so that it would speak of it more eloquently or directly. So three stars for perpetual virginity it is.