A hermeneutic that dictates that artists do as little original work as possible (rather than as much as they can), is one that respects the past and, paradoxically, allows for the development of steadily better work in the future.

Painting the Nude: The Theology of the Body and Representation of Man in Christian Art

In this book, Clayton provides us with a synthesis that places all within the context of the greater tradition of Catholic thinking on these topics and shows how, far from being a radical departure from it, the Theology of the Body is reinforcing a traditionally Christian and conservative approach to the nude in art. - Deacon Keith Fournier

Two Schemas for Liturgical Art in the 15th Century: Can You Identify These Saints?

Why Portraying God as a Gray-Haired Man Offers Hope to Radical Feminists

So much of today’s gender wars and identity politics, I feel, emanate from a poor grasp of the Christian understanding of both human and divine love. It is more common, through the popularization of the Theology of the Body, to focus on nuptial love as a type for God's love, and rightly so. But we should be careful not to neglect what the types of paternal and maternal love tell us about God's love too.

Meditation, Contemplation and Transformation; Praying With Sacred Art

In the Western/Christian tradition meditation and contemplation are two different things and often misunderstood. As a result of the The Beatles and the Maharishi Yogi, the words are often used interchangeably to apply to meditative practice of Eastern religions, which is different and less effective, in my experience, than the methods of Christian mysticism.

How to Pray With Sacred Art

The short answer to this question is just this: pray as you would normally, but look at sacred art as you do it. Good sacred art will promote a right attitude through the combination of content, compositional design, and stylistic elements. In this sense, the artist does the hard work in advance to make it easy and natural for us.

Is Nudity Appropriate in Christian Art?

Nudity has long been a staple of fine art, but many people feel it is inappropriate for an artist who is also a faithful Christian to portray nudity in their work.

Is it? The answer, as is so often the case in matters of faith and morals, is - it depends.

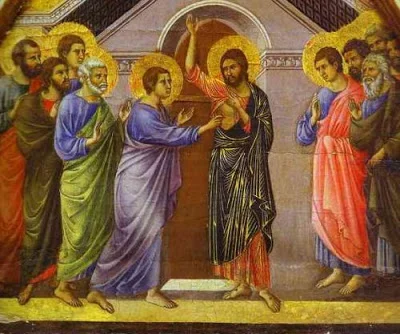

To modern sensibilities art is decoration. Usually, we are not called upon to look past the surface of what is presented. And so we focus on the external, that which we can see.

But creation consists of what we can see and what we cannot see, the visible and the invisible. It is the role of the artist to create work that draws us past the surface, what we can see, to contemplate the transcendent truth that is presented to us, that which we cannot see.

Pattern, Geometry, and Abstract Christian Art

"Geometric pattern is the abstract art of Christianity."

We tend to think of abstract as something that has come about only within the last one hundred years. But liturgical artists have had their own form of abstract art for nearly two thousand years. Geometric pattern is the abstract art of Christianity.

God made all of creation, visible and invisible, to teach us about Himself. When we perceive the order and pattern that is inherent in creation, the numbers that underlie all of creation, we see the thumbprint of God.

Geometrical forms, built up from mathematical (numerical) forms, are a symbolic expression of Christian Truth. They represent the thoughts of God.

In the Christian world, numbers have both a quantitative meaning and a qualitative meaning. They tell us the amount of some thing (quantity) but they also tell us about the thing itself. (qualitative.)

A carton of a dozen eggs, for example, holds a quantity of 12 eggs. But the number 12 also has a symbolic meaning. it may represent the 12 tribes of Israel, the 12 apostles, 12 signs of the zodiac, or 12 months of the year. Which of these symbols the number represents will depend on the context in which it is used.

In the context of a work of sacred art, depending on the other elements of the work, 12 eggs could represent the New Covenant, a new Church emerging from the "sealed tomb" of the old Law, resting on the foundation of the twelve apostles.

But this qualitative and quantitative language of numbers can also be used to construct abstract, i.e. non-representational, patterns that can lead us to contemplate heavenly things. Medieval manuscript paintings often have a geometric pattern serving as the background as a symbol of the order of heaven.

The work above is a design for a church floor, completed as part of the Masters of Sacred arts program at Pontifex University. It incorporates a specific type of scrolling pattern known as a guilloche. This is a meditation on Christ in the form of a geometric pattern.

Down the middle axis of the design are three shapes. The first shape at the top contains the symbol for "alpha," the first letter of the Greek Alphabet, The bottom shape holds the symbol for "omega," the last letter. Alpha and omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end, come together in the middle in a "Christogram" a symbol representing Christ. Jesus Christ is the alpha and the omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end. Christ is the mediator between man and God. In the ancient world, the number "2" was a mediator between the numbers 1 and 3. The number "2" then, represented a mediation between two extremes, heaven and earth, divine and human, God and man. We might also say then that Jesus, the second person of the Holy Trinity, mediates between God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

Flowing around these central shapes is a bough of laurel leaves in a guilloche pattern. Laurel leaves are a symbol of victory, Christ is victorious over sin and death. The laurel bough weaves around eight medallions which contain another type of Christogram, in this case a cross and the letters INRI. They serve to remind us that Christ obtained His victory through death on a cross, a death at which He was proclaimed Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

And "eight" medallions also have a hidden meaning. Eight is the number of the victorious resurrected Christ and a redeemed world. Eight is the sum of "7" the number of totality and completion, and the number "1," representing the singularity of God. The number "8" is used in baptismal fonts as a symbol of a new life brought from darkness into light.

The victorious Christ is the eight day, heralding a new birth and a new creation. He brings the world from darkness into light.

There is no reason we cannot imbue the design of our churches with such geometric patterns and symbols that hold a rich symbolic language revealing the truths of the invisible world that are hidden within the visible. All it takes is the knowledge, and the will.

this article originally appeared at www.DeaconLawrence.org

______________________________________

Pontifex University is an online university offering a Master’s Degree in Sacred Arts. For more information visit the website at www.pontifex.university

Lawrence Klimecki is a deacon in the Diocese of Sacramento. He is a public speaker, writer, and artist, reflecting on the intersection of art and faith and the spiritual “hero’s journey” that is part of every person’s life. He maintains a blog at www.DeaconLawrence.org

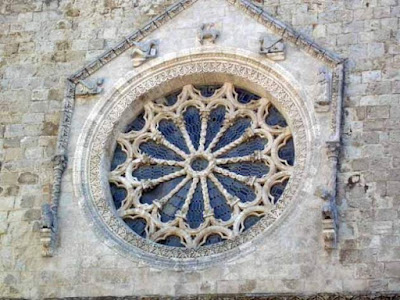

Rose Windows and Sacred Geometry - the Ancient Mystical Path to God

I have just been creating a new online course on the mathematics of beauty and as part of this, I wanted to show how to represent the symbolic meaning of number in the context of the liturgy in such a way that it might deepen participation. The obvious way to do this is to have a pattern with the symmetry of the number. This will require also some catechesis of the congregations so that they are reminded of what it is pointing to every time they see it. It can be part of the decoration of the church, incidental, as it were, to the structure:

Or it can be more intimately and obviously bound with the form of the church, as it is in the medieval rose window. Here is a window dating from about 1500 in the cathedral at Amiens in France:

It is important to awaken our innate sense of the symbolism of the natural world and all that is created as this stimulates also our natural sense of the divine. The awe and wonder that we feel when we contemplate the world around us is, for all that it seems profound, little better than a shallow emotion generated artificially by a drug if we stop there and do not allow it to draw us closer to its source - God. This is its true consummation, we are made to see the glory of God in his creation and it will be to his greater glory and our greater joy if we allow the beauty of the world to take us to what it points to.

We can consider this to be a form of relation. Creation is in relation to its Creator. By virtue of its existence, it is relational, for it is connected to its Creator by the mark of divine beauty He has impressed upon it. This interconnectivity of all that exists, therefore, is not a mental construct thrust upon the cosmos artificially by mankind. Rather it is a property of the object that we see. All being is relational by nature and is patterned lattice that has the Creator at its heart.

As created beings ourselves, we participate in this dynamic too, seeing a natural connection between ourselves and the rest of the cosmos. All of mankind is endowed by the Creator with an intellect and the capacity to observe the world around us in such as way that it can derive from it an understanding of our place within it, and ultimately this points to and sheds light on our relationship with the Creator.

Part of our task as people seeking to evangelize the world is to re-awaken the final link in the chain of connection between creation and Creator by re-establishing a culture that is rooted in this principle of interconnectivity through its beauty. This process of evangelization of the culture begins in the church in which all that we perceive and all that we do participates in this language of symbol and is there to connect us to God.

Coming back to the symbolism of number, it is widely accepted, even in the secular culture, that the natural world is connected to mathematics. The connection is so strong that few, if any, doubt, for example, the power of mathematics to help the natural scientist to describe the processes of the natural world. However, I think we should stop for a moment and think about this - it need not automatically be the case. Once I realised this it became a source of great wonder to me that the abstract world of mathematics is so intimately bound in its structure with the behaviour of the natural world.

This had to be noticed before the connection could be made, and it is why figures such as Boethius commented, in his De Institutione Arithmetica, (Bk1, Ch.2) that 'number was the principal exemplar in the in the mind of the Creator' and from this is derived the pattern of its existence that the scientist observes.

The natural scientist of today is generally less aware of the symbolism that runs through both nature and mathematics. The medieval thinker would not have rejected method of today's natural scientists I suggest but would have added to his description of the natural world the symbolic language of number, which is largely forgotten today. If scientists were to do this today, I suggest that it would inform his work in such as way that technology would both enhance his work as a conventional scientist and allow its applications to become more in harmony with the flourishing of man. Rather than being in conflict with today's scientist, the proponent of sacred number has something that can help him to be a better scientist.

Geometry is a way in which number can be expressed in space through matter, and so this is why geometric patterned art ought to be right at the heart of the evangelization of the culture and any sacred art. It is also why the study of the symbolic meaning of number in conjunction with the study of geometry is so important in a Catholic education today. What I propose is a study of geometry that is so much deeper, and more exciting than the dull task of memorizing Euclidian proofs (which sadly seems to be the way it is taught in Great Books schools today). This is about connecting the pattern of the universe to the creative impulse of man so that the beauty of the culture can direct us to God even more powerfully than the most beautiful sunset you have ever seen.

And so this is why I would like to see the rebirth of the Rose Window, in our new churches. This is more than simple decoration, if done well it has the power to stimulate in us a profound sense of our place in the world and in relation to God. Always assuming that even if we got as far as seeing them in churches, the catechesis available would be minimal or poor (we're Catholics!) these would need to be designed in such a way that the symbolism was obvious. There is nothing stopping words and scriptural quotes being added, just as we must in figurative art, in order to clarify, for example.

Here I give some examples of such windows with, three, four, five and sevenfold symmetry. I have obtained these photographs from a great resource that I discovered online called therosewindow.com, run by Painton Cowen, who kindly gave us permission to reproduce his photographs here. This site has photos of windows based upon numbers that you don't normally associate with Christian symbolism - 11 and 13 for example. I would want to consider carefully the basis of these before replicating them today. We must learn from the past, but we must be aware also that not everything that it tells us is true!

Here are some images.

Three, 15th century, Barrien, France:

Four and three in a quincunx arrangement of five objects, 15th century, Agen, France

Five, Exeter, England, 13/14th century:

Seven, Beaulieu en Rouergue, France, possibly 14th century:

If you want to know more about the symbolism of number and the philosophy behind it, I suggest that you either read The Way of Beauty or take the course, the Mathematics of Beauty which will soon be offered at www.Pontifex.University, Master's in Sacred Arts program.

In the meantime...believe it or not, lucky thirteen! Larino Duomo, Italy,

A Processional Cross by Philippe Lefebvre

Here is a newly completed wood polychrome and gilded processional cross made by Frenchman Philippe Lefebvre. I love the balance of naturalism and subtle abstraction that he has incorporated into this. In Mediator Dei, Pius XII said, you may recall: 'Modern art should be given free scope in the due and reverent service of the church and the sacred rites, provided that they preserve a correct balance between styles tending neither to extreme realism nor to excessive "symbolism," and that the needs of the Christian community are taken into consideration rather than the particular taste or talent of the individual artist.'

He is telling us that the Christian artist must represent natural appearances and through the medium he chooses reveal also the invisible truths of the human person ('symbolism'). There is wide scope for individual interpretation of how this might be done, even when working within the forms of an established tradition. It is incumbent upon each artist to find the balance that appeals to people of his day. This may mean working precisely in the way of the past, or adapting and building on the past in order to achieve this end and create something new. In doing so he must avoid the errors of straying too far in either direction, towards extreme naturalism ('realism') or abstraction.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)