Entertaining, funny, easy to watch...and noble (mostly). This film offers us lessons in how to promote the New Evangelization and offer the Mass to the masses. Really, I mean it!

The Intern is an entertaining and very funny feelgood movie which has a good story and along the way reinforces good traditional values. It has greater depth than most critics give it credit for and furthermore, I think that this shows us how the mass culture could be used constructively to draw people back to the Church and the Mass more powerfully, entertainingly and in about the half the viewing time that Into the Great Silence ever could. It also shows us what the strengths of movies are in this regard.

It is not without flaws but, I suggest, these could be easily remedied and so that it could have made a strong endorsement of Catholic social teaching. I am hoping there are some Catholic film makers watching who might take note.

Any who read last week's review will be aware of my view of what makes a good film, but for those who didn't: I hate self-consciously arty films that stress character development or visual beauty at the expense of the plot. I think that all these have to be there but a movie is successful when all serves the narrative. This means that in my view the American film industry, which understands this, is superior to the British and European; and as a rule I avoid anything that has sub-titles because I assume I'm going to be bored to death. The famous line that sums up why the British film industry is so unsuccessful (a question that discussion panels on BBC Tv and radio programs have discussed ad infinitum) is that the British directors always make films to impress their friends at dinner parties and nobody else...and they do it very well.

For this film I read the reviews first and the critics seemed to split. Some found it entertaining and funny, while others disliked it for being shallow and lacking philosophical depth. Given what most film critics require to be philosophically stimulated - angst and doom - I took both types of review as an endorsement!

As it turned out it certainly wasn't self-consciously philosophical but in fact it reveals a natural philosophy of life that is, broadly speaking, good and derived from Christian principles. It doesn't feel deep because it doesn't challenge our sense of what is good, it affirms it.

The plot is simple. A retired 70-year-old business executive and widower, Ben (Rober De Niro), is bored and looking to 'fill the hole' in his life. He had already tried getting out and being involved in activities that gave him some human contact, but this was not enough. He needed to a have purpose and so he applied for a job at a new internet startup that had subscribed to a 'senior intern' program as part of a publicity exercise. He had a job interview with the 'talent acquisition' executive in which he was asked what was obviously a standard question given to all applicants, regardless of the job: 'Where do you see yourself in 10 years' time?' De Niro's perfectly timed response was, 'You mean when I'm 80?'

This being an internet startup, Ben is just about the only employee over thirty. The comic moments relate to the clash of the generations in which each misunderstands the other. Without pushing himself on them, or complaining, he gently offers his wisdom based upon life experience and the younger people around him realise that he can help them in their work and their personal lives.

Gradually, the founder and CEO of the company, Jules Austin, (played by Anne Hathaway) starts to rely on him for advice in the same way. We realise that he is filling the hole in his life not by getting a second career, but rather by being of service to all around him in the workplace. His new job is his opportunity for service. Through his example, others start to adopt his approach in what would be an otherwise cut-throat commercial environment. We see how, through his personal interractions with the people around him, he is affecting this society in microcosm for the good and helping to make it a community.

The climax of the film revolves around troubles in the marriage of Jules Austin. Her husband, a stay-at-home dad who gave up his career when the hers took off, feels neglected and retaliates badly (if you want the details you'll have to watch the film). The film does not justify the behaviour of either, however, but instead takes them to a point of reconciliation whereby each reflects on the situation and admits independently the part they have played. Each resolves to make personal sacrifices for the other and for the marriage (there is a synchronicity to it that reminds us of O Henry and Gift of the Magi).

Although the story is simple, it is believable and the wisdom imparted through it seems true. It was also very funny and I wonder how much of this is down to the great performance of Robert De Niro whose timing and delivery are impeccable.

On the negative side, there's one risque joke, which stands out in contrast with the tone rest of the film and which, unfortunately, appears in all their publicity trailers that I have seen. Also, incidental to the plot, there are moments that go against Christian morality - for example, there is some reference to promiscuity that presents it in a positive light. These are almost to be expected nowadays, sadly.

Aside from these, the major regret that I had is the writer and director, Nancy Myers, did not in some way connect the good standards to that the De Niro character lived up to to their true source - God and his Church. I wouldn't expect a scene in which a character reads a passage from the Catechism, but it would have been nice if we had found out that Ben was a virtuous man because he was a Christian. I am guessing that the reason that this was not done is that Myers doesn't believe.

However, she almost did it.

There was an allusion to spirituality, at least, as the source of his strength. In the opening scene of the film we see Ben in the park participating in a controlled exercise routine - it looked to me like the Chinese practice of Qigong. We hear him in the voiceover describing his general disatisfaction at life as we see him doing it. In the final scene of the film, all seems to have turned out well and Jules is looking for Ben at work to thank him. She is told that he took the day off. She eventually found him in the park, back with the Qidong group. There was no discussion of what he was doing or reference to it in any other way. We just saw it as an aspect of his previous life that was something good and he he wanted to retain. This was reinforced by the fact that he asked her if she wanted to join in with him before they talked, and she did so.

I don't know if this was the director's intention but occurred to me that in an understated but powerful way, what the film had portrayed was a bit of Qidong New Evangelization! She had portrayed (perhaps unintentionally) the Christian idea of the cycle of worship: the exitus and reditus (exit and return) by which we are inspired by God and are dismissed to go out to love our fellow man. Then, transformed by our love for God through man, we come back to God as greater lovers, and the positive cycle is repeated.

How wonderful this film would have been if this little detail - the topping and tailing of the film with a spiritual reference - had been a one by which he went to a beautiful Mass. And rather than joining the stretching in the park, Jules was sat silently in the pews at church contemlating what was going on and listening to Ave Verum Corpus before they left to have their conversation.

If we want to get more people back into the Church, this film is showing us, is a small way, how to do it. So, Catholic screenwriters here's your challenge! Create a Catholic version of a film like, this. Once you have your script all you need is several million dollars and Robert De Niro and you'll have a box-office hit that promotes the Faith.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thv8myYCUQE

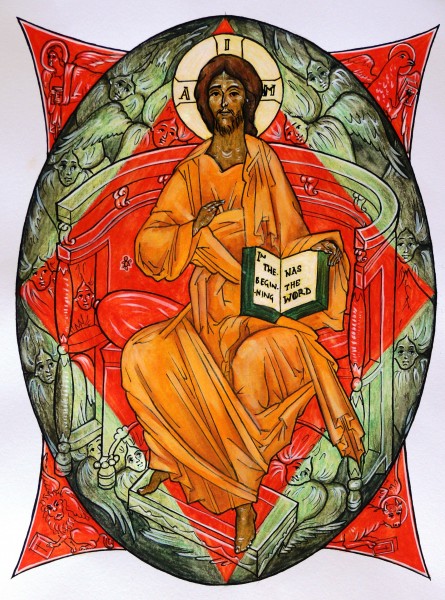

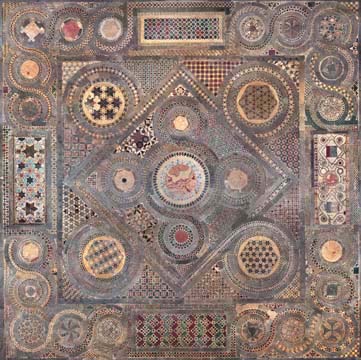

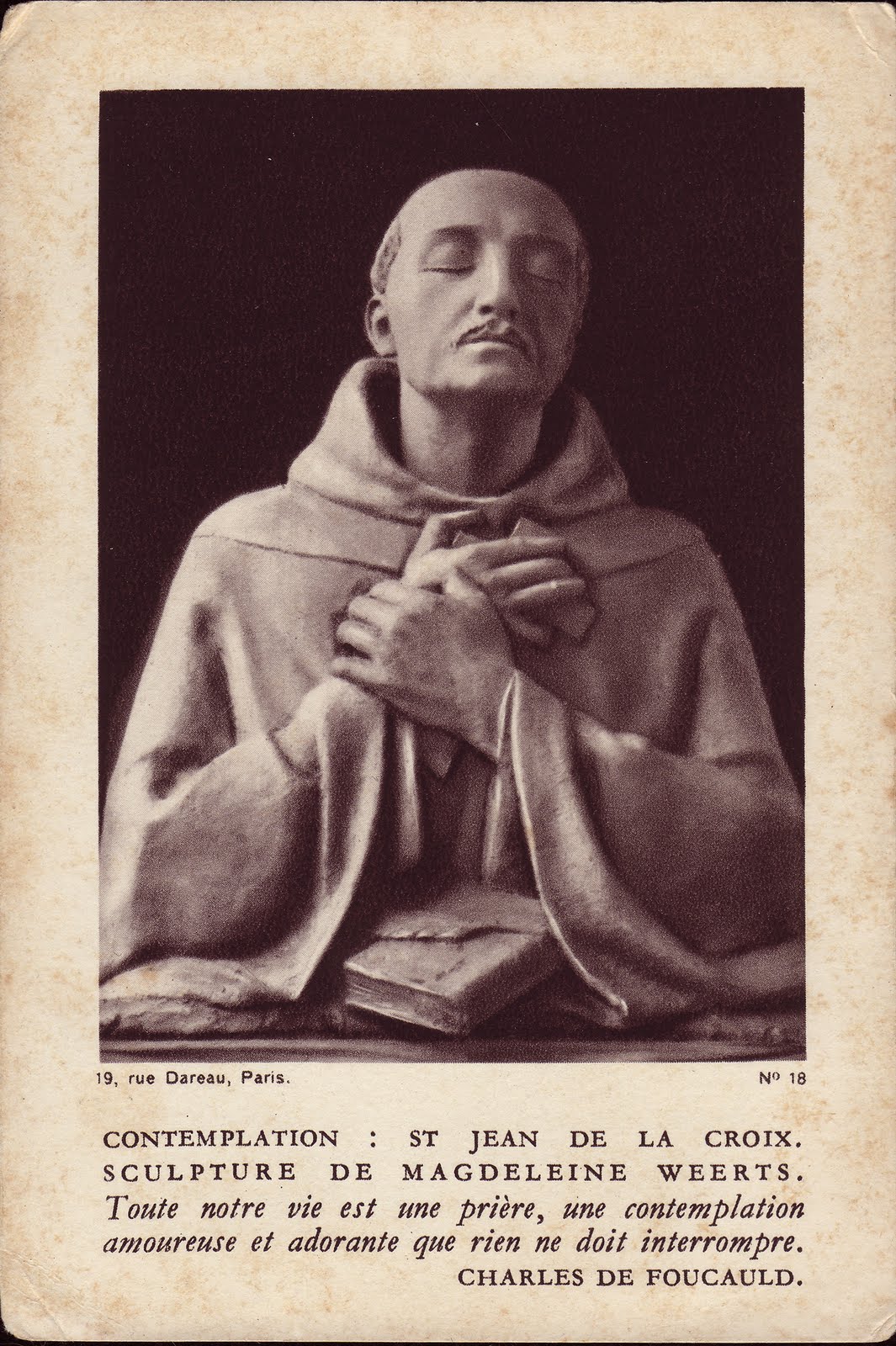

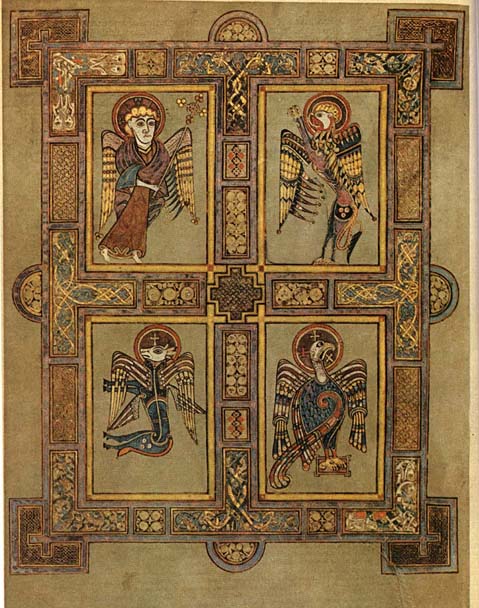

This week we show images, one is representational are and one is geometric art.

First is Christ Enthroned. I painted this for the childrens coloring book, Meet the Angels. It went on the back cover. It shows Christ, as described in the vision of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelaton, enthroned with the four faces of the Cherubim in each corner. Around the throne also are many six-winged seraphim - just wings and faces - and who are transparent so the colours of the background show through. This is a standard iconographic image and if you look on Google images for 'Christ Enthroned' or 'Christ in Majesty' you will see many in this style. It is painted in egg tempera. The almond shape around Christ is called a Mandorla (Italian for almond!) and represents the cosmos.

This week we show images, one is representational are and one is geometric art.

First is Christ Enthroned. I painted this for the childrens coloring book, Meet the Angels. It went on the back cover. It shows Christ, as described in the vision of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelaton, enthroned with the four faces of the Cherubim in each corner. Around the throne also are many six-winged seraphim - just wings and faces - and who are transparent so the colours of the background show through. This is a standard iconographic image and if you look on Google images for 'Christ Enthroned' or 'Christ in Majesty' you will see many in this style. It is painted in egg tempera. The almond shape around Christ is called a Mandorla (Italian for almond!) and represents the cosmos.