This event is inspiring, informative and uplifiting! The Catholic Education Foundation – convinced by history and the present reality – believes that the viability of our Catholic schools is largely dependent on the support and involvement of our priests.

The Love of Learning and the Lay Desire for God

What lessons does the monastic approach to learning classical texts bear on our contemporary debates in education? Speaking to the College of Bernardins in Paris, Pope Benedict XVI used a beautiful image about the importance of monks singing well together to make an analogy about how we can learn to seek God together in education. Beautiful music is supposed to generate resonance—a feeling that stays with us; perhaps a gentle, uplifting feeling that gently calls our attention towards the sublime. But the opposite of resonance is dissonance, not being able to put together all the pieces of what you are hearing.

I had students in a seminar on education read Pope Benedict’s piece because dissonance in education today is rampant. Students rarely are exposed to classes that teach them how to integrate knowledge from various fields. Students accumulate tons of information, but they have no way to put together all the pieces of what they learn. They are also taught that the only truth is relativism about truth. Rather than education being a journey that forms us integrally as humans, education becomes a chore that (even if we succeed at it) fragments us.

My own studying of medieval monastic approach to learning has not led me to flee to the hills in a segmented community, but to develop an approach to education that has provided my students with precisely the kinds of resonance that learning is supposed to provide—an integration of knowledge that helps integrate one’s own very being in the world.

Pope Benedict described the monastic approach to learning as Quaerere Deum—setting out in search of God both through revelation and through nature. He called this a “truly philosophical attitude: looking beyond the penultimate, and setting out in search of the ultimate and the true.”

To know God is not only to know Scripture; to know God is also to know his action in the world as revealed in the history and world of human beings. God not only created the world, but continues to work in the world. As such, our work in the world can be seen as “a special form of resemblance to God, as a way in which man can and may share in God’s activity as creator of the world.”

Because the monks believed that God was at work in whatever was beautiful, in his book The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, Jean Leclercq describes how monks studied not only Church Fathers and Scripture, but classical texts simply because they were beautiful. Monks believed that, in some real way, everything that is good or beautiful comes from the hand of God, even if the author was not a Christian.

According to Leclercq, monks were optimistic in thinking that “everything true or good or simply beautiful that was said, even by pagans, belongs to the Christians” (116). Quite unlike today’s efforts to deconstruct and debunk classical texts for their flaws, monks made every effort to find a good intention in these works.

Monks studied scripture with great appreciation for God’s word, but they also studied non-Christian works that were beautiful and good simply to develop their appreciation for the beautiful, wherever it was. As Leclercq describes, the monks sought to:

Develop in all a power of enthusiasm and the capacity for admiration . . . Wisdom was sought in the pages of pagan literature and the searcher discovered it because he already possessed it; the texts gave it an added luster. The pagan authors continued to live in their readers, to nurture their desire for wisdom and moral aspirations (118-119).

The Monks appreciated the beauty of classical texts, and not merely because they were Christian or even moral instruction. As Leclercq explains,

At times they drew moral lessons from these authors, but they were not, thanks be to God, reduced to looking to them for that. Their desire was for the joys of the spirit, and they neglected none that these authors had to offer. So if they transcribed classical texts it is simply because they loved them (134).

Leclercq describes this approach to learning as integral humanism, a humanism that integrates classical humanism with the eschatological humanism of Christianity: that Christ became man to save us from our sins. Integral humanism seeks beauty in both the horizontal and the vertical—the world we can see and study and the world we do not see directly, yet perceive through the beauty of the world that is a sign of another type of existence.

Integral humanism is not anthropocentricism. Integral humanism can connect the worldly and the supernatural, awakening desires for truth and deep appreciation for beauty. Integral humanism celebrates nature and man’s creation, but also acknowledges its limits and dependence on the creator, and awakens our desire for the infinite.

Discussions about liberal arts cannot just be about which texts to include in a core curriculum. Christians in particular bring a unique perspective to liberal arts education not just because of the emphasis the Christian intellectual tradition places on philosophy or theology, but, more importantly, because Christians believe that all that is good, beautiful, and true comes from the hand of God.

European culture, according to Pope Benedict XVI in Quaerere Deum, grew out of this monastic approach to knowledge that revered the word of God and all of creation. He wrote that, “what gave Europe’s culture its foundation—the search for God and the readiness to listen to him—remains today the basis of any genuine culture” (emphasis mine).

But Pope Benedict XVI goes on to argue that today, we live in a culture that has made our deepest desire—to know God—a subjective, individualized search, cut off from how we use our reason about the world. Anthropocentric humanism celebrates the human capacity to know the world but separates that capacity from how we know God. Instead of elevating our humanity, anthropocentric humanism fragments knowledge and our very being as humans into disjointed pieces.

Instead of a university in which we know all fields relate to each other and that all truth glorifies God, we have a multiversity, which might succeed in producing some good things but fails to produce resonance in students, that is, a lasting impressing that our knowledge gained is part of our quest for truth.

Most modern universities where I have worked fail to generate a sense of appreciation for any traditions of knowledge and instead promote the deconstruction of past knowledge. The curriculum may be full of laudable skills to be acquired on the way to achieving learning goals in a particular class. Yet, the idea that mastering a subject should be a transformation that awakens our desires for the good and beautiful sounds, at best, sentimental, therefore unrelated to reason, or, at worst, a romantic dream that is the privilege who those who do not need a job when they graduate.

Perhaps I am lucky to have come from a home that instilled such high aspirations in me—not just about credentials and grades, but about the love of learning. For as long as I can remember, I loved learning. My father—who studied math in college and wooed my mother by tutoring her in math—taught me when I was five about mathematical theories as a sign of his love for me.

I can recall how, as a young child not even old enough for school, I used to sit next to my father studying math or geography. I felt like the world continents as well as the world of abstract reasoning about numbers was exciting. My father was teaching me something about my place in this world, instilling in me a deep curiosity about how this all came to be so. I, in turn, always greatly admired my father’s broad intellect and intrinsic love of knowing and teaching me many, many things—both material and abstract. I have long desired that exhilarating feeling that echoes with our deepest aspirations as humans when I master a topic. I rejoice when I can pass on to a student not only mastery of a topic, but the very love of learning itself.

In an educational system so dominated by credentials and skills, we are at risk of never awakening in students their desire for the truth and killing their love of learning. It is precisely through awakening desires to know the truth that our ever-more complex educational system can function like a big orchestra—all coming together to produce beautiful harmony. Instead, many students will go through the multiversity not sure which of the many loudspeakers competing for their attention they should devote their energy to. Students tell me again and again that when they get to college, even if they may be gathering up knowledge and winning accolades, their inner soul is experiencing dissonance.

I agree with the critiques others have made about higher education, but I think the biggest challenge in higher education is not that students are hyper-competitive, stressed out, and emotionally fragile—it is that students are not getting a real education. I do not just mean they are not being exposed to the classics traditionally taught in humanities classes; I mean they are not being taught to love the search for truth that all education must aspire to.

I think it is unlikely that majors in humanities are going to grow in their numbers to even their previous levels. The pull is too strong to major in STEM fields or some other field that will make money to pay off crushing debt and a rising cost of living. But integral humanism in education, or, more generally, a classical liberal arts education, could also mean that students majoring in any field could go on trips to the art museum together; or, go to a monastery for a day, or even longer. These are a couple of the many ways to awaken their full humanity in its search for the truth in every situation.

For example, in the summer seminar I taught for the last two summers entitled “Rediscovering Integral Humanism,” both shared experiences of beauty, alongside long sessions poring over texts, were important part of our time together. We spent several days at Oxford reading authors like John Henry Newman, Jacques Maritain, and George Marsden. In our free time, we went to Evensong at Magdalene College, or went for walks in nature. During our eight days at Ampleforth Abbey, a Benedictine monastery near York, we not only continued our intense pace of study, we also walked to see the sheep and pigs at the monastery, played games together outdoors, ate meals family-style around a big table, and sang the liturgy of the hours with the monks, or just sang with each other spontaneously.

Studying and living together at a monastery for eight days made the monastic approach to education come alive. It is not just that the animals and fields are beautiful, it is that the beauty inspires creativity and deep thinking. Open landscapes helps us open our mind. Stunning sunsets over the lake excite the senses, call our attention both outward and inward at the same time, preparing us to think deeply and slowly in our reading sessions.

As one student remarked in her evaluation,

The setting of the seminar, particularly in Ampleforth, made it very natural to stay in a contemplative mindset. And living and eating together made it feel like we were a family, with all the relational depth and play that goes along with that kind of dynamic. The readings/discussions exposed me to many different viewpoints and disciplinary approaches, while also giving me a much deeper understanding of my own area of study; I was able to view it—and was forced to articulate it—from the perspectives that others brought to the discussion.

This particular student was from a family of eight children, had attended Princeton University on a full financial need scholarship, achieved great accolades in the classroom and service, and had been active in a Christian ministry. But the seminar we shared together was unique because it allowed her to enter into a contemplative mindset, to get to know others' perspectives and personalities, as one does with siblings, and to be challenged by each other’s ideas in the seminar discussions.

But I was perhaps even more struck by her expression of how the seminar resonated with her humanity, leaving an impression that she is known and loved; with a feeling that that our time together was permeated by something bigger than all of us (the love of God) that holds us together. As she wrote:

My most lasting impression from the seminar will be the infusion of God’s love in all of our time together. I felt whole, like I was known and loved. The lingering taste of these deep and beautiful friendships will, I hope, lead me onto communities that will foster my growth in wisdom and self-giving wherever I’m called to next.

Beyond the material we mastered—which was quite a lot—the experience resonated with her deepest longings to search for truth with others, and the delights of the mind were shared alongside experiences of beauty.

The most profound memory I will take back with me from our time together at Ampleforth was walking in silence as a group for about an hour from the monastery to the lake to see the sunset together on the last evening. I noticed how everyone’s walking style was slightly different. Some were slow while others practically ran. Some looked like they were skipping, whereas others swayed side to side.

When we arrived at the lake, we stood in a big group by the lake and made a circle, hugging each other as I offered my final reflection on our twelve days together. I remarked that our distinct walking styles headed in the same direction reminded me that each of us came here on a journey, and our journey was personal, yet we are accompanying each other on our journey. We are in fact, self-interpreting animals who seek the company of other self-interpreting animals. As a Christian, I believe that humans are part of nature, we build many things including culture and, yes we have the image of the divine in us that can be communicated to others in love.

The beauty of that final moment together in nature solidified for all of us our memories of what an amazing experience we had together. I told the students that in times of worry and doubt—times that I know will come as I am a weak human—I will remember our lively seminar discussions, our singing, our walks in nature, our many shared meals, our intensely personal conversations, and find my faith, hope, and love renewed in remembering you.

The seminar was an experience of our total humanity in a world that feels so fragmented. My final words to the group were to go forth in love to a world that feels polarized, divided, angry, and confused. The love of God we felt pouring out during our search for truth together is something we need to communicate to others—not just to our friends who think us like, but also to those who do not understand us, and those who do not want to understand us. A monastic approach to education does not have to mean creating communities apart from the world, but can also mean witnessing by our approach to learning a greater truth—that, despite our often grave differences, we are all on a journey together, united as creatures of one God that we all seek, perhaps by different names that point to one reality.

The monastic approach to education—Quaerere Deum—fits well with our seeker generation whose lives are filled with dissonance in their education and their personal lives. Many of today’s young people—regardless of their faith background or where they are on their faith journey—desire to live a theological aesthetic in their everyday lives, which have been stripped of the sacred.

Seeking God in all things—revelation and nature, seeing God active in faith and in reason—is a bulwark against the dominant language of science that is empiricist—the only thing that is real is material. Such an approach to the world reduces all of created reality to something to be manipulate. Quaerere Deum is a bulwark against educational practice that lead to endless deconstruction of truth—there is goodness and beauty in the world, there is truth we can discover and share with others. The critical approach cannot lead us anywhere without the appreciation of the beautiful and the good.

But a response to our crisis in education through learning once again to seek God in all things is not a formula, nor a curriculum, but a journey, one that takes its time, that goes deep, and in so doing, slowly transforms the world around it, even a world that may seem hostile to it. Like a great piece of music, Quaerere Deum, an approach to education that is both deeply satisfying yet also leaves us longing for more: the infinite.

This article was originally published at Church Life Journal.

Why Choose Mystery Over Ideology?

When I took a wrong turn while driving with students in Rhode Island in the summer of 2019, we found ourselves driving over a bridge clouded in fog, seemingly going into nowhere. When we came out of the fog, I tried to make a U-turn and ended up going around several jughandles before getting back on the same foggy bridge going the other direction.

Back in our classroom at Portsmouth Abbey and School in Rhode Island, students drew an image of a car going over a bridge into the fog to represent Luigi Giussani’s educational philosophy as described in his book The Risk of Education. Giussani paints a picture of education as an adventure in which we start off our journey feeling as if our inner light is clouded in fog, but we have faith that we can reach certainty about our questions. Reaching certainty then leads us to ask other questions, and we go into the fog again, with confidence that our journey is not in vain.

For the past five summers, I’ve gathered with students through a Scala Foundation program to ponder contemporary challenges in education. For many students, schooling has become so-called strategic learning—studying for a certain grade on a test. Other students gravitate toward activism—learning for the sake of changing the world.

Giussani’s writings on education become memorable precisely because they evoke reactions whereby students experience precisely what they’ve been missing in education—curiosity and questioning. Just like the sense of adventurous joy we felt as we crossed the foggy bridge in Rhode Island, Giussani sparks my students’ imagination. Reading Giussani together, it’s like we have set off into the fog, riding together, getting excited about what we learned, and then turning around, ready for more.

Giussani’s emphasis on mystery is one idea that seems “relevant” to students. What “problem” does the notion of mystery solve for them? Giussani unpacks for students just why a so-called problem-solving approach to education, where all knowledge must have relevance to change this world, has unintended consequences. What students are missing in education today are awe, curiosity, and contemplation. The beginning of education is not changing the world, but being attentive to all of reality, including its symbolic dimension.

Why has our modern system of education become obsessed with problem-solving to the detriment of a contemplative view of education? Could it be possible that we are so obsessed with transforming the world that we’ve lost the joyous adventure of forming the inner dynamism of young people to lovelearning?

Central to Giussani’s vision of education is his view that reality—both human nature and the things we create with knowledge—has a symbolic dimension. As Giussani writes, human reason is not only about discovering causal laws, but our reason looks at reality as a sign: “Our nature senses that what it experiences, what it has at hand, refers to something else. We have called this the ‘vanishing point.’ It is the vanishing point that exists in every human experience; that is, a point that does not close, but rather refers beyond.”

For Giussani, humans are beings who live in a particular time and history. Yet we also have a cosmic origin and final end of communion with God. That’s why Giussani emphasizes that education has to form young people in reason and faith, science and mystery, action and contemplation.

Students come to my seminars to ponder questions like: How does a liberal arts education form us as integral persons—mind, body, and soul? What is poetic knowledge, and how is it related to scientific and conceptual knowledge?

Jacques Maritain’s work Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry, delivered as a series of lectures in the spring of 1952, is both history of art and philosophy of humanity. Maritain’s Creative Intuition is an exploration into the spiritual preconscious from which stems poetic knowledge that helps unite beauty, truth, and goodness. As with his other, perhaps better-known works, Maritain’s exploration of art and poetry points to a similar conclusion: there is a part of the human person that is an irreducible mystery where the encounter with God happens, but that inner element of us is profoundly shaped by the practical intellect through which works of art and poetry are created.

One of Maritain’s main claims is essentially one about intellectual history and culture: poetic knowledge has been forgotten. For many, only the scientific method is ever objective, whereas literature, poetry, art, and other forms of beauty can be nothing but subjective.

Maritain aims to restore the relationship between reason and beauty, stating, “Reason does not only consist of its conscious logical tools and manifestations, nor does the will consist only of its deliberate conscious determinations. Far beneath the sunlit surface thronged with explicit concepts and judgments, words and expressed resolutions or movements of the will, are the sources of knowledge and creativity, of love and supra-sensuous desires, hidden in the primordial translucid night of the intimate vitality of the soul.”

As part of our rational nature, therefore, art and poetry are capacities to be honed, refined, reflected on, growing gradually toward perfection. Because art and poetry bring new objects into the world, Maritain argues they form part of the practical rather than the speculative intellect: knowing for the sake of action, of bringing something into existence. Participating in art and poetry forms our identity and subjectivity into beings who have stable inner qualities that enable us to use our many human capacities for the good.

In his book Education at the Crossroads, Maritain directly engages with perhaps the most influential philosopher in American education: John Dewey. For Dewey, the scientific experiment is the only road to objective truth. In A Common Faith, Dewey wrote, “There is but one sure road of access to truth—the road of patient, cooperative inquiry operating by means of observation, experiment, record and controlled reflection.” Dewey called his approach to knowledge nothing less than a “a revolution in the seat of intellectual authority.”

Religious creeds, which used to be thought of as indicating objective knowledge, must be separated for Dewey from religious experience. Religious values are important to democracy, but “their identification with the creeds and cults of religions must be dissolved.”

Observing European politics in the first half of twentieth century, the Italian philosopher Augusto Del Noce feared that reducing values to subjectivity and enshrining only science as true quickly leads to scientism, a reduction of all truth to the scientifically verifiable. The most powerful in society are those who claim the mantle of scientific truth. As he wrote, once rendered subjective, every argument about values becomes seen as “merely ideology” and “an instrument of power.” Without shared objective values, a greater separation between elites and the masses emerges. Our social fabric tears.

Maritain warned that the downstream impact of Dewey’s philosophy, which negates contemplative truth, is a culture that will end in a “a stony positivist or technocratic denial of the objective value of any spiritual need.”

Are we surprised that today so many students today lack meaning, purpose, and hope?

One poorly understood aspect of this crisis of meaning is the neglect of the relationship between beauty, truth, and virtuous living. At my seminars, students are eager to talk about how to recover poetic knowledge alongside scientific knowledge (scientific method) and conceptual knowledge (abstractions, like laws, procedures, rules).

Experiences of beauty awaken our desire to know the splendour of the truth and prepare us to enter into virtuous relationships characterized by self-gift.

Understanding poetic knowledge as a virtue of the intellect helps explain why education must expose students to beauty. Beauty is poorly understood in much of education and culture as just one more form of self-expression rather than a form of self-transcendence. The classical understanding of beauty was that experiences of beauty awaken our desire to know the splendour of the truth and prepare us to enter into virtuous relationships characterized by self-gift.

Yet many educational institutions have forgotten beauty. Our technological society provides endless sources of entertainment that are like junk food: images and soundbites momentarily satisfy a craving to experience something, but then leave people with a deeper need for true nourishment for the soul.

The result of the neglect of objective beauty in education and culture is that much of our schooling stops at teaching us how to manipulate the world. Most educators, administrators, and policy-makers have lost sight of the power of beauty to draw students into contemplation of beauty and truth in ways that give them meaning, purpose, and hope.

In my recent book, The Love of Learning: Seven Dialogues on the Liberal Arts, I ponder the crisis in modern education with seven scholars, all of whom practice a life-giving form of liberal arts education.

In one dialogue, George Harne, a professor of music, former president of Magdalene College, and now dean of the University of St. Thomas–Houston, explains, “There is an irreducible dimension to poetry, as there is to life. We want students to recognize through liberal learning that sometimes you cannot cross all the ‘t’s and dot all the ‘i’s. There are parts of life that are irreducible in their complexity; the process of understanding life is always unfinished. Poetry can prepare us to encounter the mysterious in life, and it can inoculate us against certain ideologies that claim to explain and control everything.”

Without experiences of beauty to draw us into contemplation, education risks becoming purely cognitive and functional and culture becomes desiccated.

In another chapter of my book, the mathematical physicist Carlo Lancellotti says, “We live in a crisis of abstraction. We think that once we have analyzed things, that’s all there is, that the idea is exhausted by our analysis. Everything gets filtered through some kind of pre-prepared abstract screen. Experience is replaced by our abstract explanations of experience. What is really missing for so many today is the perception of beauty, and beauty as an opening to the mystery of God.”

Humans are made for something more than utility, problem-solving, and relevance. Beauty is the door that opens onto that greater reality. Without experiences of beauty to draw us into contemplation, education risks becoming purely cognitive and functional and culture becomes desiccated. What we learn is rendered as a set of techniques for manipulating the natural world (natural sciences) and our fellow human beings (ideologically tainted social sciences and humanities). We lack shared stories that unite us.

Beauty is the spark of liberal arts education and scientific creativity. Beauty draws us out of ourselves, arrests our attention, and leads us to contemplate our world, the people around us, and ultimately God. Beauty is the glimmer, the gleam of being. Beauty awakens our hearts to the splendour of being alive and the desire to know reality in its fullness and complexity.

The void left by the denigration of beauty and a classical liberal arts education is directing more and more people to “woke” social justice activism or alt-right movements because those movements offer them meaning, purpose, and hope, as well as community and a sense of belonging. Others burn out psychologically or resort to social isolation because trust and intimacy are hard to experience. Yet others resort to drugs, pornography, or another temporary pleasure to fill the void. Still others pursue ambitious and demanding careers without reflecting on how they should live or why they exist to begin with. The result is skyrocketing rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide. Educational institutions have not succeeded in addressing these problems, leading many people to seek alternatives to feed their minds and souls.

The students I teach are dying to return to learning as a mysterious adventure. Social justice activism, for instance, offers this adventure, but if our social and political commitments end up reducing our contemplative side to purely subjective experiences, then we have—perhaps unwittingly—adopted an underlying view of the person and of reality that has eradicated mystery.

If all knowledge is a tool to change the world, then man, not God, is at the centre of reality. Anything at all is possible, but nothing is true. For today’s generation, as for the students Giussani taught, the idea that our scientific knowledge can create any reality we want with no limitation rings hollow. Ideologies abound because soundbites promise simple explanations. But ideology never produces a well-rounded human person—without which, Guissani warned, social or political good cannot come about.

Beauty is the glimmer, the gleam of being.

As Giussani wrote, “If we consider our nature to be the image of the mystery that made us, to be participation in this mystery, and if we understand that this mystery is mercy and compassion, then we will try to practice mercy, compassion, and fraternity as our very nature whatever the effort involved.”

Integral human formation must recover education in beauty as the seed to sow the fertile ground to cultivate the fruits of intellectual virtue, restore the love of learning, and bring joy and trust into friendships, all the while retaining the personal discipline required to master and prudentially use knowledge.

My students often ask, What can unite us socially and politically? I respond that in order to reunite as a society, we have to reunite beauty, truth, and goodness. We have to choose mystery over ideology.

Article originally published by Comment Magazine.

Take Pontifex University's Master of Education in Catholic School Administration.

Pius XI On What Catholic Education Ought to Be, And What It Ought Not to Be (As Seen in Public Education)

The Way of Beauty at St Stephen's Catholic School, Grand Rapids

Talks in Grand Rapids Michigan by David Clayton, 20, 21, 22 June on Beauty in Education

Catholic Education Foundation Seminar for Bishops, Priests and Seminarians, Florida, July 11th-14th, 2022

Scala Foundation - Playing a Crucial Role in the Evangelization of the Culture and Breaking the Mould of Education

Attend the spring conference, Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good, at Princeton, NJ, April 30th, 2022. Free to register and attend.

I want to highlight the work of the SCALA Foundation. The Scala Foundation’s mission is to renew American culture by restoring beauty and wisdom to the liberal arts. Scala’s seminars, reading groups, conferences, summer programs and online resources help educators and culture creators engage the millennia-old tradition of liberal arts education and its power to form virtuous, purpose-driven citizens, form young leaders who are pivotal agents of cultural renewal, and build communities of like-minded cultural entrepreneurs and magnify their impact.

Some may remember that I recently spoke on the Scala webinar, listen here. or here. She has also invited me to be on a panel for the SCALA 2022 conference - Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good - in Princeton NJ this April, which is free to attend.

The focus of SCALA is in creating creative communities at a local level that are able to contribute to Catholic education locally and to the culture through the creation of art, music, literature etc (eg she organizes writers' workshops).

It occurs to me that SCALA is offering programs that complement formal online education, such as that offered by www.Pontifex.University, where I work, and when the two approaches to student formation are combined offer a genuine opportunity. The zoom revolution that has happened as a result of Covid has opened up people’s minds to the idea of online education.

The advantages of this are that high-quality and standardized educational material can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of the traditional on-campus experience. However, I am conscious that providing community of learning - so important in education - is the weakness of online education and while things are improving, it is clear that Facebook pages and chatrooms don't fill the gap. This is where SCALA comes in. They are guiding educators and artistic creatives who can contribute to a culture of beauty to form communities locally.

I am encouraging Pontifex students to attend and participate in the conferences and events and meet each other, (and me if they are interested!) so that they might start to form communities with each other locally under Scala's guidance. It is these local communities, it occurs to me, which might be portals for grace and love that can transform the culture.

Join Us for a Webinar on Art, Education and Cultural Renewal, Thursday 30th September

Catholic Education Foundation Seminar for Bishops, Priests and Seminarians, Florida, July 13th-15th

New Catholic Classical Academy in San Francisco, K-12

stellamarissf.org. It is through the communities founded on the pillars of the family, the school and the parish that hope for evangelization will emerge.

Using Sacred Art to Protect Children from Pernicious Internet Imagery

A Book that Offers A Template for Catholic Education for Children

I am often asked how my book, The Way of Beauty, which describes the principles of Catholic Education at higher levels, can be adapted for younger children. Now I know where to send them...here!

This wonderful book, written by a professor of education from Notre Dame University, Sydney, Australia, has the answers and much more besides. Balancing the natural and the supernatural, the theoretical and the practical, and combining the best of traditional methods with modern educational theory and psychology (with great prudence), Gerard O'Shea describes how a mystagogical catechesis, rooted in the study of scripture and the actual worship of God is at the heart of every Catholic education. Then he describes how teaching methods and curricula should reflect these principles for children of different ages.

The Mystery of Mystagogy! Catholic Education is an Education in the Liturgy...nothing else!

As described before, on my return from the Sacra Liturgia 2013 conference in Rome I wrote an article for Catholic Education Daily in which I argued that the essence of Catholic education is education in the liturgy. The article is A School of Love: the Sacred Liturgy and Education. As part of the recommended reading of the conference and since writing this I got around to reading Sacramentum Caritatis. Within the section on 'mystagogy' this very matter is discussed directly.

Mystogogy means literally in Greek, 'learning about the mysteries'. Mystagogy in this context is, to quote Stratford Caldecott ‘the stage of exploratory catechesis that comes after apologetics, after evangelization, and after the sacraments of initiation (baptism, Eucharist, and confirmation) have been received’ and is sometimes referred to a formal stage of education of the newly baptised Christian in living out the faith.

As described before, on my return from the Sacra Liturgia 2013 conference in Rome I wrote an article for Catholic Education Daily in which I argued that the essence of Catholic education is education in the liturgy. The article is A School of Love: the Sacred Liturgy and Education. As part of the recommended reading of the conference and since writing this I got around to reading Sacramentum Caritatis. Within the section on 'mystagogy' this very matter is discussed directly.

Mystogogy means literally in Greek, 'learning about the mysteries'. Mystagogy in this context is, to quote Stratford Caldecott ‘the stage of exploratory catechesis that comes after apologetics, after evangelization, and after the sacraments of initiation (baptism, Eucharist, and confirmation) have been received’ and is sometimes referred to a formal stage of education of the newly baptised Christian in living out the faith.

Section 64 of Pope Benedicts XVI's encyclical Sacramentum Caritatis is entitled 'Mystagogical Catechesis'. In this he says:

'The Church's great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one's life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world...The mature fruit of mystagogy is an awareness that one's life is being progressively transformed by the holy mysteries being celebrated. The aim of all Christian education, moreover, is to train the believer in an adult faith that can make him a "new creation", capable of bearing witness in his surroundings to the Christian hope that inspires him.'

Once again, the full article is here.

Catholic Education Daily is run by the Cardinal Newman Society which is dedicated to the promotion of faithful Catholic education in our schools and colleges.

A School of Love: Sacred Liturgy and Education. Reflections after Sacra Liturgia 2013 in Rome

How do you teach Catholic engineering? What does it mean to be a Catholic plumber? The answer lies in the liturgy.

I was invited to attend the conference on the Sacred Liturgy Sacra Liturgia 2013 in Rome by the Cardinal Newman Society and asked to write my thoughts on what I hear and how it might impact Catholic education. This was an inspiring three days. This was the Benedictine (as in our wonderful Pope Emeritus) understanding of liturgy made manifest. I will feature the articles over the next few weeks. Before I present what I wrote for them I just want to say what a star Archbishop Sample from Portland Oregon is. He spoke on how a Bishop can introduce changes in the liturgy in his diocese. He impressed my as being totally dedicated and able to win people over without compromising on principle.

How do you teach Catholic engineering? What does it mean to be a Catholic plumber? The answer lies in the liturgy.

I was invited to attend the conference on the Sacred Liturgy Sacra Liturgia 2013 in Rome by the Cardinal Newman Society and asked to write my thoughts on what I hear and how it might impact Catholic education. This was an inspiring three days. This was the Benedictine (as in our wonderful Pope Emeritus) understanding of liturgy made manifest. I will feature the articles over the next few weeks. Before I present what I wrote for them I just want to say what a star Archbishop Sample from Portland Oregon is. He spoke on how a Bishop can introduce changes in the liturgy in his diocese. He impressed my as being totally dedicated and able to win people over without compromising on principle.

In this article I discuss what is meant by a Catholic education, especially when you are teaching things that don't seem instrically religious, such as science. The link is here.

Founded in 1993, the Cardinal Newman Society has a mission to promote and defend faithful Catholic education.

What Teaches Wisdom - Poetry, Clear Prose or Beautiful Art and Music?

An education in truths that cannot be expressed in words

In his book, the Love of Learning and the Desire for God, Jean Leclerq describes various tensions playing out in education in the medieval period.

An education in truths that cannot be expressed in words

In his book, the Love of Learning and the Desire for God, Jean Leclerq describes various tensions playing out in education in the medieval period.

One arises from the love of beautiful literature, poetic or prosaic, that is not explicitly sacred. The danger is that at some point the beauty of these works is so compelling that it hampers the spiritual development of the individual, because ‘Virgil might outshine Holy Scripture in the monk’s esteem because of the perfection of his style’[1]. A properly ordered asceticism in this area consisted in a harmonization of sources and sometimes the more humbly written simple prose divinely inspired Scripture is necessary for us so that we focus on the beauty of what it directs us to, he says.

The second tension that Leclercq describes relates to the study of logic, or sometimes called dialectic, which is another of the first three liberal arts that together comprise the trivium. As such it requires an understanding the technical language of logic. It is necessary in order to study philosophy and theology. The difference arose between two different sorts of school, the monastic and the town scholastic schools. The word scholastic is derived from the Latin word meaning ‘school’ and is applied to distinguish it from the monastic setting.

One the one hand is the more traditional monastic school that is more literary, drawing on Biblical language and traditional literary forms.

The monastic schools of the medieval period recognized the value of dialectic, but were suspicious of scholastic Schools in which there was a tendency, they felt, for dialectics to dominated to the detriment of the other liberal arts, and especially those concerned with the beautiful expression of what is true and good. As Leclercq puts it: ‘ The Scholastics were concerned with achieving clarity. Consequently they readily make use of abstract terms, and never hesitate to forge new words which St Bernard [as an example of an authority from the monastic school] for his part avoids. Not that he refuses to use the philosophical terminology which through Boethius had come down from Aristotle…but for him this terminology is never more that a vocabulary for emergency use and does not supplant the bibilical vocabulary. The one he customarily uses remains, like the Bible’s, essentially poetic. His language is consistently more literary than that of the School.’

And in the use of this traditional technical vocabulary there also exists a certain diversity: each monastic author chooses from the Bible and the Fathers his favourite expressions and gives them the shade of meaning he prefers. Within the overall unity there remains a variety which is characteristic of a living culture.’[2]

The strength of this is great flexibility is a noble accessibility and beauty that opens the door and draws in the ordinary reader to receive the wonders they describe; the weakness is its technical imprecision so that it can be ambiguous and this leads to a greater possibility of misinterpretation.

Those seeking to offer a Catholic education today are likely to draw on both the monastic and scholastic influences. Even in the few Catholic ‘Great Books’ programmes that exist today we can see how a polarization might develop, some favouring either poetic knowledge on the one hand or of a formal Thomistic training on the other. This needn’t be so. As a general principle, I suggest, the way to avoid extremes of an over emphasis on the poetic form on one hand and an overemphasis on dialectic on the other is to make prayer and the liturgy the central, harmonizing principle of the life of the student and professor alike, whether monastic or scholastic. This is something more than encouraging participation in the liturgy. It is making the participation in the liturgy the guiding principle in what and how we learn and teach. The students should understand clearly how everything that they learn is done in order to deepen our participation in the liturgy. In this regard, the liturgy of the hours is a crucial presence, I suggest. Then the praying of the liturgy will in turn illuminate the lessons learnt in the classroom.

In light of this I suggest there are aspects of education that are neglected in Leclercq’s account. He focuses almost exclusively on communication by language. I wonder if this is too narrow a vision. The teaching of truth expressed linguistically is the most important part of study, but it should not be emphasized in a way that excludes the visual and musical. A formal study of perceptible beauty, especially visual and auditory aspects of harmony, proportion and order is in the traditional study of the quadrivium. St Augustine[3] spoke of how the beauty of the form says things that words cannot.

There are levels of understanding that cannot be said in words alone, even poetic words, that can only be communicated visually or through words when they are sung beautifully. Any lover of holy icons would say the same, I suggest, in regard to visual beauty. Giving ourselves a beautiful visual focus for our prayer, especially Out Lady, the suffering Christ and the face of Our Lord is important in this regard.

Liturgy is the place where all of this can be synthesized and one is immersed in God's wisdom and this, deep in the heart of the person, is where we form the culture.

[1] Ibid, p124

[2] Ibid, p201

[3] St Augustine, On Psalm 32, Sermon 1, 7-8; quoted in the Office of Readings for the Feast of St Cecilia, November 22nd

A Recommended Book for Young Children

Here is a book introducing young children both to an aspect of the Faith and to the artistic traditions of the Church. It is not an unusual idea - there are other books for children making use of the works of Old Masters. However, this one caught my eye because it uses exclusively the art of one artist, Fra Angelico, which gives the project greater cohesion than many. Also, I love Fra Angelico, so anything that introduces his art to children is worth looking at in my opinion.

Bethlehem Books, the publisher, says that this is 'a first board book in a set on the Blessed Trinity. The aim of The Saving Name of God the Son is to help guide the child listener and adult reader into the mystery of the Son of God, Jesus Christ'

Here is a book introducing young children both to an aspect of the Faith and to the artistic traditions of the Church. It is not an unusual idea - there are other books for children making use of the works of Old Masters. However, this one caught my eye because it uses exclusively the art of one artist, Fra Angelico, which gives the project greater cohesion than many. Also, I love Fra Angelico, so anything that introduces his art to children is worth looking at in my opinion.

Bethlehem Books, the publisher, says that this is 'a first board book in a set on the Blessed Trinity. The aim of The Saving Name of God the Son is to help guide the child listener and adult reader into the mystery of the Son of God, Jesus Christ'

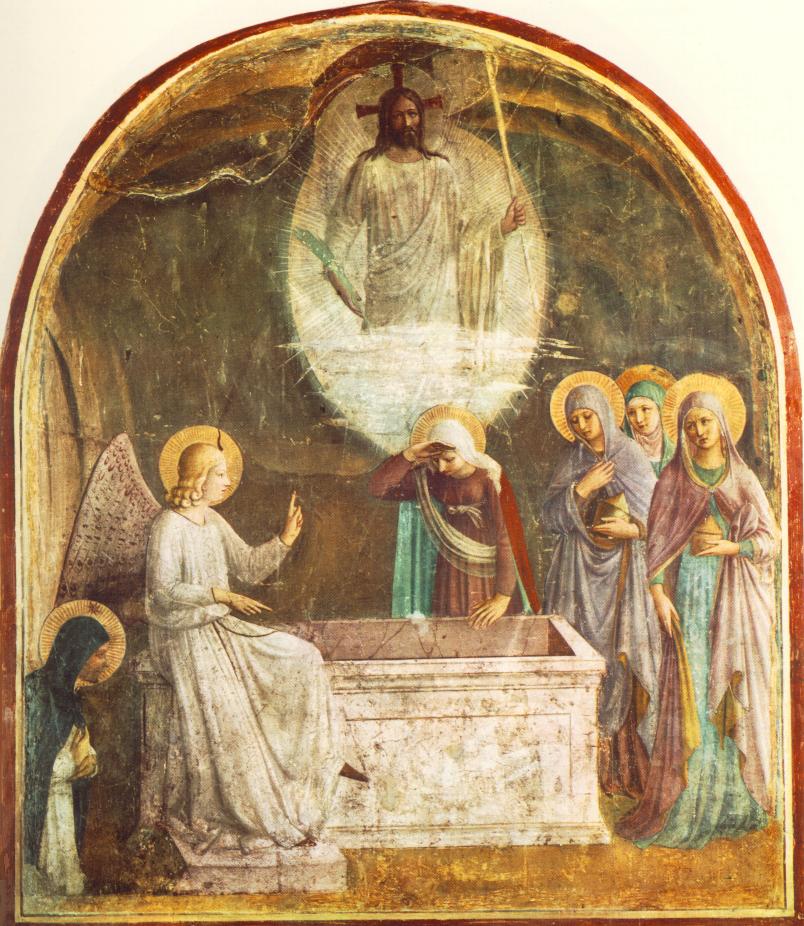

There are ten described events, including The Resurrection, below, and with the front cover this makes 11 reproductions. There are very few words, perhaps two or three short sentences per picture, but they are taken from Scripture or the Catechism and it has been put together so that it runs smoothly, simply and understandably. Given the source of the text and the quality of the reproductions, I can imagine that it is likely to give the grown-ups doing the reading a resource for some pictorial lectio. At the back are comprehensive details about each picture (name, location of original etc) and the sources for the accompanying text, plus scriptural readings and sections of the Catechism that reinforce the theological point being made.

To get more information or order The Saving Name of God the Son, go to Bethlehem Books website, here. Bethlehem Book publish this as part of their Holy Child teaching curriculum and present many ideas about how to use this book with different age groups to maximise the enjoyment and the quality of the educational experience, here.

There is an additional exercise that I would encourage. If parents encourage their older children to copy these beautiful images as best they can then it will impress the style of this wonderful artist upon their souls in some way and, who knows, it might stimulate a future Fra Angelico to realise his or her vocation!

Thomas More College links up with Internationally Known Atelier, Ingbretson Studios, Again

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at Ingbretson Studio, the internationally known studio of Paul Ingbretson in Manchester, New Hampshire. This is ideal for those want to go to college and get a Catholic formation, but don’t want to leave their art behind while they study. Thomas More College of Liberal Arts continues to be the one place where you can study both.

This was a course run for the first time last semester and it was so successful that we are giving up to a dozen undergraduates the chance to learn this traditional method again. Through this they will receive a training that will give them a level of skill in drawing that is greater than many leaving a conventional art school after four years' study. The photographs shown are of the drawings produced by last year's students.

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at Ingbretson Studio, the internationally known studio of Paul Ingbretson in Manchester, New Hampshire. This is ideal for those want to go to college and get a Catholic formation, but don’t want to leave their art behind while they study. Thomas More College of Liberal Arts continues to be the one place where you can study both.

This was a course run for the first time last semester and it was so successful that we are giving up to a dozen undergraduates the chance to learn this traditional method again. Through this they will receive a training that will give them a level of skill in drawing that is greater than many leaving a conventional art school after four years' study. The photographs shown are of the drawings produced by last year's students.

Paul Ingbretson is a modern Master of the Boston school and is one of those I mentioned who was given his training by Ives Gammell in the 1970s. He has been teaching ever since. His school has an international reputation (we were all well aware of it, for example, when we were studying in Florence). He teaches the rigorous 'academic method' of drawing which can be traced back to the methods of Leonardo da Vinci and was used by figures such as Velazquez and more recently, John Singer Sargent.

By coincidence Ingbretson Studios is just 10 minutes drive from the TMC campus. Those who have a strong enough interest will also have an opportunity to train full time for three solid months each summer if they wish to do so. This is part of the college art guild of St Luke in which students are able to learn also traditional iconography and sacred geometry.

I teach a course to all freshmen who attend the college called The Way of Beauty in which students learn in depth about Catholic culture, especially art and architecture, and its connection to the liturgy.

Public Lecture Series Scheduled for the Fall in New Hampshire

I have been invited to give a series of six public lectures through the Fall on traditional forms in art at the Exhibition Gallery of the Sharon Arts Centre in downtown Peterborough, New Hampshire. This is not a Catholic or even Christian organization, but reflects a growing (if perhaps not yet burgeoning) interest from secular circles in traditional art forms including Christian forms of art and this invitation is a hopeful sign. The first lecture is on Tuesday, September 6th at 7:15pm at the gallery space which is at 30 Grove Street in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They take place semi-monthly in September, October and November 2011.

In this series I will not only discuss the form of the Christian traditions of geometric, iconographic, gothic and baroque forms. There will be lectures also, towards the end of the series on how non-Christian art such as Islamic, Hindu and Taoist art and even non-religious 20thcentury modern art reflects their respective worldviews. This is a distilled from my course, the Way of Beauty that is taught as part of the core curriculum at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, NH

I have been invited to give a series of six public lectures through the Fall on traditional forms in art at the Exhibition Gallery of the Sharon Arts Centre in downtown Peterborough, New Hampshire. This is not a Catholic or even Christian organization, but reflects a growing (if perhaps not yet burgeoning) interest from secular circles in traditional art forms including Christian forms of art and this invitation is a hopeful sign. The first lecture is on Tuesday, September 6th at 7:15pm at the gallery space which is at 30 Grove Street in Peterborough, New Hampshire. They take place semi-monthly in September, October and November 2011.

In this series I will not only discuss the form of the Christian traditions of geometric, iconographic, gothic and baroque forms. There will be lectures also, towards the end of the series on how non-Christian art such as Islamic, Hindu and Taoist art and even non-religious 20thcentury modern art reflects their respective worldviews. This is a distilled from my course, the Way of Beauty that is taught as part of the core curriculum at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, NH

There will be time after each lecture for some discussion and for socialising.

For more details see here or the Upcoming Events page on this blog.