When Pope Benedict XVI spoke recently to assembled artists (in the broadest sense of the term) in Rome, he was echoing John Paul II and Paul VI in calling for a new culture of beauty. Benedict emphasised strongly, perhaps even more strongly than his predecessors, the importance of the evangelization of the whole culture and how beauty is a principle that can inform all human activity – work and leisure as well as worship. When we work beautifully, we work gracefully ie with God’s grace, and we are travelling on the ‘via pulchritudinis’ - the Way of Beauty - which leads us ultimately to God and attracts others to Him.

When Pope Benedict XVI spoke recently to assembled artists (in the broadest sense of the term) in Rome, he was echoing John Paul II and Paul VI in calling for a new culture of beauty. Benedict emphasised strongly, perhaps even more strongly than his predecessors, the importance of the evangelization of the whole culture and how beauty is a principle that can inform all human activity – work and leisure as well as worship. When we work beautifully, we work gracefully ie with God’s grace, and we are travelling on the ‘via pulchritudinis’ - the Way of Beauty - which leads us ultimately to God and attracts others to Him.

If this broader evangelization of the culture is to happen, it must begin with orthodox, dignified and beautiful liturgy. It must, in my opinion be closely followed by the art, architecture and music that is united to it. This will set the form that becomes the model upon which all aspects of the culture are based, just as it did in the past.

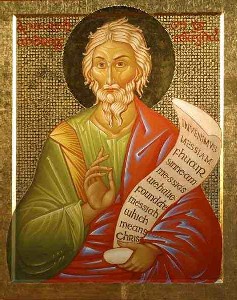

At the moment, the re-establishment of iconography is slightly further ahead than that of naturalistic Western art (as a sacred art form) and our Eastern brethren are setting the pace in this respect. Like Western art, iconography (even in the East), had degenerated under the influence of the Enlightenment. (For further discussion on this see the article about icons, here). Its resurgence began first in the Eastern Church in the mid 20th century, with figures such as the Greek artist Photius Kontoglou and the Russian émigré based in France, Gregory Kroug. Under their influence, the next generations of iconographers have come through. The Western Church has lagged behind slightly in this respect, perhaps 50 years (maybe hampered by the difficulties in its liturgy). However, just as we see light at the end of the liturgical tunnel now in the West with what I have heard people refer to as the ‘Benedictine Restoration’ (as in Pope Benedictine XVI), we do now see Catholic iconographers are beginning to emerge. One is Sr Petra Clare, who is a Benedictine nun based in a skete in the Scottish Highlands. It is a bus ride northwest of Inverness in a village called Cannich and it is a truly beautiful spot to visit if you get a chance. Here are some examples of her work. You also can see her website here. I first became aware of her work through visits to Pluscarden Abbey near Elgin in northern Scotland. She was commissioned by the abbey to paint two large icons, a John the Baptist (or John the Forerunner) and a St Andrew (seen here). They are facing the monks in the choir and visitors sitting in the transcepts have to strain their necks slightly to see them, but it’s worth the effort.

Sr Petra's style is probably closest to that of the Russian school. When I have written about her work in the past, some have questioned the validity of having an Eastern style in the Western liturgy. Shouldn't we, they say, use some of our own iconographic traditions? After all we have Carolingian, Ottonian, Celtic and Romanesque styles that all conform to the iconographic. My thoughts are that we have to start somewhere good, which Sr Petra does, and there has always been cross fertilisation in iconographic styles. Also, the Romanesque itself, was a style formed by contact with the East and when it began resembled greatly the Greek Eastern styles. Gradually, a distinct voice developed naturally. Also, I would say that Sr Petra is an experienced icon painter and without ever seeking to force it we can see her own style coming through. Who's to say that isn't Western?

Below: St Luke, left; and right, St Andrew. More of Sr Petra's work can be seen at www.sanctiangeli.org