Landowners have a duty to leave some food for the poor and give people access to get it. Or that's what it looks like at least. Here are two scriptural passages taken from the Office of Readings (part of the Liturgy of the Hours) that caught my eye when I read them. One is from January and the other is a Lenten reading. Office of Readings 24th Jan 2011, Commemoration of St Francis de Sales: "You must not pervert justice in dealing with a stranger or an orphan, nor take a widow’s garment in pledge. Remember that you were a slave in Egypt and that the Lord your God redeemed you from there. That is why I lay this charge on you. When reaping the harvest in your field, if you have overlooked a sheaf in that field, do not go back for it. Leave it for the stranger, the orphan and the widow, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all your undertakings. When you beat your olive trees you must not go over the branches twice. Let anything left be for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. When you harvest your vineyard you must not pick it over a second time. Let anything left be for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt. That is why I lay this charge on you." (Dueteronomy 24) And Tuesday 4th week of Lent “When you gather the harvest of your land, you are not to harvest to the very end of the field. You are not to gather the gleanings of the harvest. You are neither to strip your vine bare nor to collect the fruit that has fallen in your vineyard. You must leave them for the poor and the stranger. I am the Lord your God.(Leviticus 19) I have written on a number of occasions, here, that land is considered by the Church a common good. This means that like air and food it is something that should be available to all people. This does not mean that there should not be private property however, provided that private ownership of property is viewed as an entitlement to work the land. This privilege of ownership brings obligations. Its use should be for the benefit of the common good. This is not so completely counter cultural as it might sound at first. Generally, growing crops on a farm; and then selling anything (beyond what is needed for personal consumption) for distribution through the market is in accord with this. This entitlement, however, and this part might be counter cultural in some parts of the world, is not always seen as extending to allowing the owner to exclude others from his land all the time, as the quoted passages above indicate.

Landowners have a duty to leave some food for the poor and give people access to get it. Or that's what it looks like at least. Here are two scriptural passages taken from the Office of Readings (part of the Liturgy of the Hours) that caught my eye when I read them. One is from January and the other is a Lenten reading. Office of Readings 24th Jan 2011, Commemoration of St Francis de Sales: "You must not pervert justice in dealing with a stranger or an orphan, nor take a widow’s garment in pledge. Remember that you were a slave in Egypt and that the Lord your God redeemed you from there. That is why I lay this charge on you. When reaping the harvest in your field, if you have overlooked a sheaf in that field, do not go back for it. Leave it for the stranger, the orphan and the widow, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all your undertakings. When you beat your olive trees you must not go over the branches twice. Let anything left be for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. When you harvest your vineyard you must not pick it over a second time. Let anything left be for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt. That is why I lay this charge on you." (Dueteronomy 24) And Tuesday 4th week of Lent “When you gather the harvest of your land, you are not to harvest to the very end of the field. You are not to gather the gleanings of the harvest. You are neither to strip your vine bare nor to collect the fruit that has fallen in your vineyard. You must leave them for the poor and the stranger. I am the Lord your God.(Leviticus 19) I have written on a number of occasions, here, that land is considered by the Church a common good. This means that like air and food it is something that should be available to all people. This does not mean that there should not be private property however, provided that private ownership of property is viewed as an entitlement to work the land. This privilege of ownership brings obligations. Its use should be for the benefit of the common good. This is not so completely counter cultural as it might sound at first. Generally, growing crops on a farm; and then selling anything (beyond what is needed for personal consumption) for distribution through the market is in accord with this. This entitlement, however, and this part might be counter cultural in some parts of the world, is not always seen as extending to allowing the owner to exclude others from his land all the time, as the quoted passages above indicate.

In a number of European countries (I know of England, Scotland, Spain and Italy specifically) there is public right of way preserved in law, on privately owned land. This is a tradition that goes back to medieval times. While the landowner is obliged to allow people on his land, those who go onto the land are also obliged to respect the property and the crops that are growing respecting it's function as contributing to the common good. I don't know if any applications of this extend to being in accord with the passages from the bible, which clearly allow for "the stranger, the orphan and the widow" to go onto the land and gather food.

There is an American version of this approach, as I understand it whereby in some states the default situation is that people do have access to private land to hunt. In New Hampshire there is an option to pay a higher land tax and that allows you then to bar everyone else from your land. I wouldn't be interested in hunting, just the chance of finding a walkable path across farmland. I did find one farm west of Nashua, NH when I was living there that had a notice saying. Please do come an enjoy our farm land but we ask that you respect it. I don't know if it was a coincidence, but the was a large statue of he Virgin Mary very visible next to the farmhouse as we walk off the land.

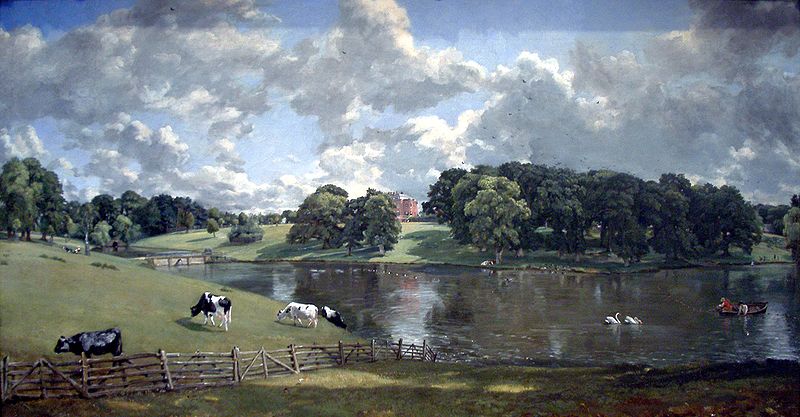

It seems that perhaps the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council and those subsequently who actually revised the Office of Readings considered this an important principle for today; otherwise it would not have been included in regular readings in the Church's liturgy. I believe that access to the land is important even for those who are not so poor that they need to pick the crops for personal use. It is important for the soul, I think. And this means access to cultivated land, productive land, not the wilderness. It is good to have firsthand experience of man's productive and harmonious activities with nature. This shapes not only the view of nature, but the view of man's proper relationship with the land.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.

I do not believe that this alone will reverse the culture of death (abortion exists in Europe too). However, if any discussion of these ideas in both Europe and the New World is combined with the example of what people see if they have access to cultivated land it will, I feel, speak of man's positive impact on the natural world. This then could help to change views on man's relationship with Creation. The change will not occur through engagement in discussion, so much as through a subtle influence that seeps into the thinking of society. Then perhaps, in some small way at least, it could contribute to the transformation a culture in the reverse direction to what is happening now and which is so anti-human.

So it seems that the dictum, spare the rod and spoil the child doesn't extend to olive trees! The photograph below of the Tuscan countryside. Above that we have Spanish olive groves and an illumination from Crete dating from the Byzantine rule.