The Via Pulchritudinis or Way of Beauty has application in anything that can be designed and one expert website designer, Adam Solove, has started to incorporate these traditional ideas into what he does. He has written about the project here. He says that the results are better and simpler to implement than the design methods he was shown as a student: something called a Swiss grid; or the Golden Mean, which is the ratio observed in nature so often.

Adam has replaced this with one of the Boethian series referred to in my article on Harmony and Proportion, called the Fourth of Four. As he points out, this is the same as the famous Fibonacci series, named after the Italian mathematician Fibonacci, who is credited with introducing the series into Western mathematics in 1202...but Boethius's De Arithmetica, in which it appears also, dates from the 6th century AD and so predates Fibonacci by several hundred years. And Boethius tells us that he got the series from works by the ancient Greeks before him.

The Via Pulchritudinis or Way of Beauty has application in anything that can be designed and one expert website designer, Adam Solove, has started to incorporate these traditional ideas into what he does. He has written about the project here. He says that the results are better and simpler to implement than the design methods he was shown as a student: something called a Swiss grid; or the Golden Mean, which is the ratio observed in nature so often.

Adam has replaced this with one of the Boethian series referred to in my article on Harmony and Proportion, called the Fourth of Four. As he points out, this is the same as the famous Fibonacci series, named after the Italian mathematician Fibonacci, who is credited with introducing the series into Western mathematics in 1202...but Boethius's De Arithmetica, in which it appears also, dates from the 6th century AD and so predates Fibonacci by several hundred years. And Boethius tells us that he got the series from works by the ancient Greeks before him.

I am very excited by what Adam is doing and encourage readers to go to his blog, here, to read more about what he is doing. I can't show you a photo of his first example as it is for a website that won't be launched for some time yet. In what I saw he devised his page so that it was 8 units across and then divided used relative lengths of 5 and 3 up and down the page. This is the broad layout. Then he subdivided these blocks into 3, 2, 1 relative lengths for smaller inserts, subsections and so on.

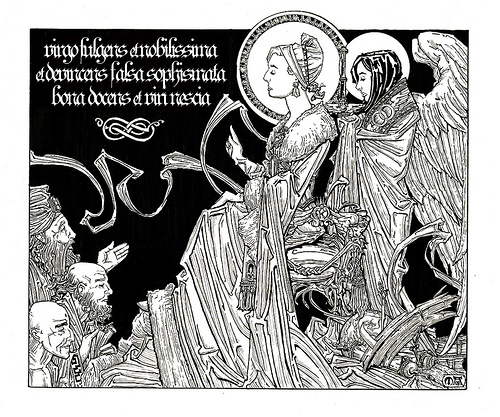

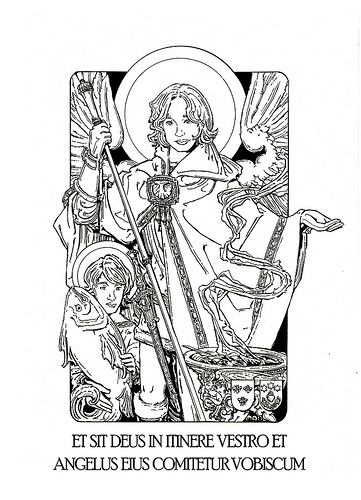

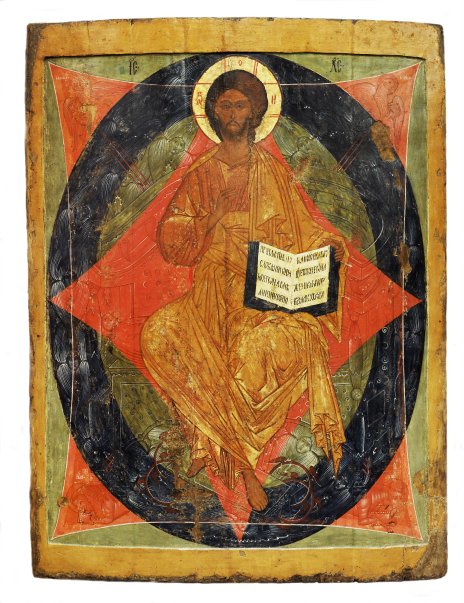

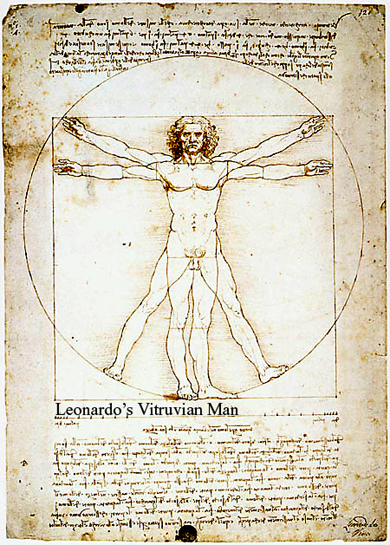

The Fourth of Four, like the Fibonacci series, tends towards the Golden Mean proportion as the number of terms increases. It is interesting that the modern interest is on the end of the series, that is, the Golden Mean. The ancients were uninterested in this aspect it seems, but chose instead to focus on the beginning of the series. The Church Fathers such as St Augustine identified the proportions given at the beginning of the series (3:5:8) with the perfect proportions for the ideal man, who is Christ and who embodies the harmony of the cosmos.

It is a personal view, but I question whether the Golden Mean is in fact worthy of the appellation 'Golden'. It was only in the Renaissance that it was called 'Golden' and my research suggests that the level of its use before the the 20th century has been exaggerated. It was only ever used consciously used by artists occasionally and in the Renaissance when the term Golden was coined. (This is despite all those diagrams in art books with grids placed over photographs of the of Parthenon or the pyramids in Egypt). But that's a discussion for another day.

Why is there this different focus one wonders? I would account for it by considering the difference between traditional Christian and the modern secular worldview of nature and man's place in it. Modern man looks at what nature is and considers it perfect (as long as man hasn't messed around with it). The Church Fathers on the other hand observed nature but sought to perfect it by considering what it ought to be. They considered the world in which we live to be beautiful, yes, but nevertheless imperfect due to the Fall. Therefore, they sought to emulate perfect nature rather than fallen, imperfect nature. Employing the Golden Mean, which is the modern obession, is to emulate fallen nature. (I have written about this here.)

So for the ancients the Ideal proportions at the beginning of the Fourth of Four are not employed as an approximation to the Golden Mean. It is the other way round. What we now call the Golden Mean (the ancients never called it this) if it represents anything it is the Fall and is better understood as a degraded version of the ideal proportion.

Adam has kindly offered to help me create our accompanying website, which I hope to get going in the next few weeks. This will be an ordered presentation of the whole Way of Beauty vision; and an archive of the written material both from the blog and of additional longer articles that I wish to post, which I will start referring to in the blog. We will work together on this project and make it open to fellow traveller on the via pulchritudinis.