This is written by icon painter Aidan Hart (my teacher who is based in England). When reading the following, the reader should be aware that the in the Orthodox Tradition the form of liturgical art is restricted to the iconographic (that which, as Aidan puts it below, aims to ‘manifest the world and saints transfigured’). So when he refers to liturgical art, he is equating it in his mind with iconographic art. Catholic liturgical art includes the iconographic tradition and so in principle, we can accept what Aidan has said about it here. However, Catholic liturgical art is not restricted to iconography. In his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy Benedict XVI states this and adds the two great Western traditions of the gothic and the baroque as authentic Western liturgical forms. These aim to reveal different aspects of the mankind and so are complementary to the iconographic form (as a recent article discusses).

This is written by icon painter Aidan Hart (my teacher who is based in England). When reading the following, the reader should be aware that the in the Orthodox Tradition the form of liturgical art is restricted to the iconographic (that which, as Aidan puts it below, aims to ‘manifest the world and saints transfigured’). So when he refers to liturgical art, he is equating it in his mind with iconographic art. Catholic liturgical art includes the iconographic tradition and so in principle, we can accept what Aidan has said about it here. However, Catholic liturgical art is not restricted to iconography. In his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy Benedict XVI states this and adds the two great Western traditions of the gothic and the baroque as authentic Western liturgical forms. These aim to reveal different aspects of the mankind and so are complementary to the iconographic form (as a recent article discusses).

------------------------------------------------------------

"When faced with the craze for novelty in contemporary art it is too easy to stress the unchanging nature of the icon tradition. We even read in some books that the icon painter must paint according to strict canons, as though he or she were expected to paint by numbers. Where does the truth lie between freedom and conformity for the way icons are painted? Or any liturgical art is created?

The answer is found not in the style but in the subject and the recipients. At Pentecost the one Gospel was preached in many languages because the truth couldn't be bounded by any one culture. And people needed to receive the truth in a form that they could comprehend.

It is a fact that the icon tradition in all its healthiest periods - both East and West - has great variety within an identity of spirit and purpose. This is attested by the fact that we can usually date an icon to within thirty years by its style alone, and give its provenance with reasonable accuracy. Great diversity in unity is a fact in icon history rather than a proposition. Romanesque, Russian, Byzantine, Georgian, and early Roman art - to take just some examples - all manifest the same vision but using their distinct dialects.

It is a fact that the icon tradition in all its healthiest periods - both East and West - has great variety within an identity of spirit and purpose. This is attested by the fact that we can usually date an icon to within thirty years by its style alone, and give its provenance with reasonable accuracy. Great diversity in unity is a fact in icon history rather than a proposition. Romanesque, Russian, Byzantine, Georgian, and early Roman art - to take just some examples - all manifest the same vision but using their distinct dialects.

But where does the mean lie between unspiritual innovation on the one hand and mere duplication on the other? Genuine variety in liturgical art occurs when the iconographer unites spiritual vision with artistic ability - energized with courage and the blessing of God. Vision without artistic ability produces pious daubs. Not every saint can paint icons. Although icons are more than art, but they are not less than art.

Ability without spiritual vision can produce one of two results.

If the iconographer limits him or herself to copying, then their works will certainly function liturgically but will lack spirit and authority. Such icons will be a painting of a painting of the saint rather than a painting of the saint. They will be the equivalent of a portrait made from photographs rather than from live sittings. The Evangelist Matthew records that Jesus taught the people "as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Matthew 9:29). It was because He knew the Father that Christ spoke with authority. Likewise the apostles. "We declare to you what we have seen and heard," wrote John (1 John 1:3). When iconographers paint from experience their works possess naturalness, freshness and boldness.

If on the other hand the painter is of a more adventurous bent and experiments but without spiritual vision, then their works will tell us more about themselves than the holy subject. Their paintings might be admirable for their daring but be more art than icon.

If on the other hand the painter is of a more adventurous bent and experiments but without spiritual vision, then their works will tell us more about themselves than the holy subject. Their paintings might be admirable for their daring but be more art than icon.

When an icon painter has vision plus ability but does not have the courage to do more than simply copy, it is to my mind a sad thing and it misrepresents God's nature. It is like the person in the parable who buried their talent. It was because they believed that the giver was " a hard man" that they were "afraid and went and hid the talent in the earth" (Matthew 25:24,25). Such fearfulness suggests that God has made us machines rather than mysterious beings of great depth and variety, made in His image. Monotony of style in liturgical art also suggests that God Himself is somewhat finite, able to be expressed in just one style. It is a form of spiritual meanness.

Vision, ability and courage in equal abundance is a rare trinity. This being the case, perhaps devout and careful copying of masterpieces in the spirit of humility rather than fear is the best compromise. But this copying is just a stop gap. It should not be accepted as the definition and apogee of tradition, any more than the recitation of patristic texts can be asserted as the zenith of teaching ability.

Why discuss the style of religious art at all, we might ask? Surely it is the icon's holy subject matter that makes it a holy image rather than its style? This is true to some extent: "The honour given to the image passes over to the prototype" wrote St Basil the Great (On the Holy Spirit 18.45).

Why discuss the style of religious art at all, we might ask? Surely it is the icon's holy subject matter that makes it a holy image rather than its style? This is true to some extent: "The honour given to the image passes over to the prototype" wrote St Basil the Great (On the Holy Spirit 18.45).

But it is also true that the way a subject is depicted has great impact on the way we see the subject. There is a profane way of depicting sacred things, and a sacred way of depicting mundane things.

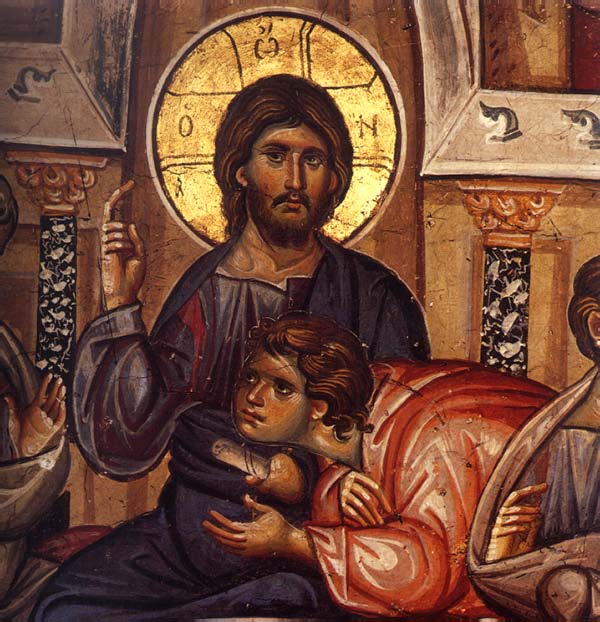

In the Orthodox Church, liturgical art aims to manifest the world and saints transfigured by the indwelling Holy Spirit, like Moses' bush that burned without being consumed [see introductory note, DC].

By its means as well as its subject matter, liturgical art can help us see the world with the eye of the spirit, and not merely with the physical senses. What St Paul wrote of his preaching can also be the aspiration of all liturgical artists:

"Now we have received not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit which is from God, that we might understand the gifts bestowed on us by God. And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths to those who possess the Spirit" (1 Corinthians 2:12,13)." "

The images are all of the Annunciation. From top: by Aidan Hart; 12th century Russian; 12th century English from the St Albans Psalter; contemporary Neo-Coptic; early 14th century Byzantine; 12th century, Mt Sinai.

I am ashamed to admit it, but when I arrived here in the US, I knew relatively little about the founding fathers of the country. Most of what I knew came from the HBO series John Adams, which focussed on the life of the second president of the United States. As it turned out, I now realise, this wasn't a bad introduction to the subject.

I am ashamed to admit it, but when I arrived here in the US, I knew relatively little about the founding fathers of the country. Most of what I knew came from the HBO series John Adams, which focussed on the life of the second president of the United States. As it turned out, I now realise, this wasn't a bad introduction to the subject.

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics

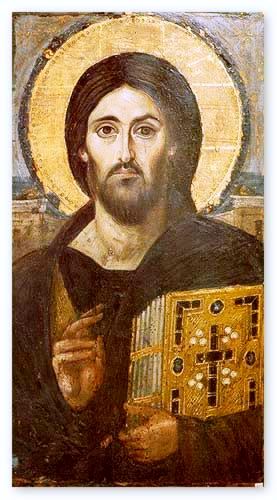

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics  There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.