I recently read

The Liturgical Altar by Geoffrey Webb. Originally written in 1936 and republished just last year, this has been referred to a number of times by New Liturgical Movement writers. I was reading it, as one might expect, to try to find out more about the design of altars, but a short section at the end where he discusses general principles caught my eye.

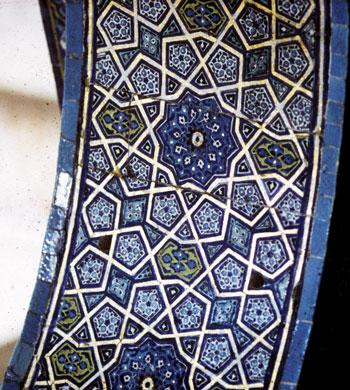

He wrote: ‘Anyone familiar with what remains of the forms of liturgical art in England before the break in religion in the sixteenth century must be impressed with one characteristic feature in it. Its beauty appears to share with the wild flowers, and with all the natural order, that absence of toil and effort to which Our Lord Himself drew attention in the lilies of the field. Beauty is an essential attribute of God; and some visible reflection of it would seem to be an inevitable accompaniment of any true worship of God, whenever the spirit of the Liturgy is allowed to give a form to the arts. At certain periods in the Church’s history this visible beauty overflows into all the arts of everyday life. This is the case when the Church can so permeate a whole civilization that she is free to distribute other benefits over and above the one essential blessing of Faith. At such times, education, in the sense of formation of good taste and sound judgment, becomes the common property of the whole community; and the common things of daily use seem to share in the unself-conscious beauty of nature…Beauty, unless ruled by the Cross, generates the seeds of its own destruction.’

Geoffrey Webb is describing a time when the culture of faith and the wider culture reflect common values. This wider culture might be thought of as the everyday practices of living that reflect, and in turn reinforce, the values, priorities and beliefs of a society. He mentions the 12thcentury, but the same could be said of all of the period up to the end of the gothic and then after the High Renaissance in the baroque period. The culture that came out of the Church’s counter-Reformation, the 17th century baroque, was so powerful that it was adopted by the protestant countries of Europe as well.

If the link between the culture of faith and the wider culture is broken so that it reflects values other than those of the faith, you have an unstable situation. The two cannot sit side by side and without affecting each other. A Catholic social ghetto is not the answer, for even the most cloistered monk cannot help but be affected by the society in which he lives. In time cross-fertilisation will occur and the stronger will dominate and eventually overcome the weaker. Either faith will affect the culture and evangelise it; or the wider culture will infect culture of faith and then destroy faith itself.

The need to to repair the bridge between the wider culture and culture of faith in order to evangelize the culture, was impressed upon me just last year by visiting lecturer at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, Fr. Rob Johansen (of the diocese of Kalamazoo, and currently working on his Licentiate in Liturgy at the Liturgical Institute at Munderlein.) He spoke eloquently of how the culture not only reflects, but also reinforces the 'values, priorities and beliefs' of society.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview.

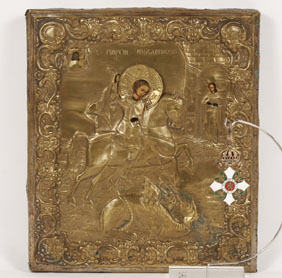

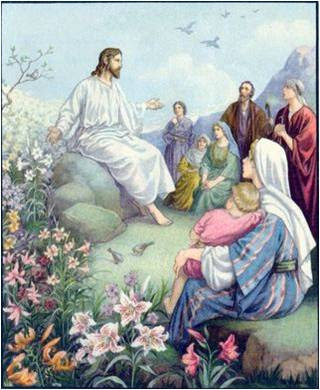

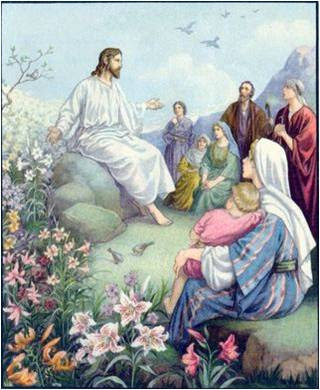

Inset into the text are examples of each. First a crucifixion from 1912 by Emile Nolde, which reflects the style of the mainstream art movement of the time. Second, left, we have a modern prayer card in which the artist, in my opinion, relies to heavily on sentiment. It is lacking an authentic Christian visual vocabulary that exists within, for example the baroque, and so is unable to communicate its message with vigour.

Writing in 1936, Geoffrey Webb says that his ideal of divine beauty is absent in both secular and liturgical art. Liturgical art has, he says, ‘lost the spontaneous and creative spirit, and that feeling for the beauty of nature which is so characteristic of the Psalms.’ In other words, the culture of faith has been infected by the wider culture. Contrast this with the power and vigour of the third painting inset into the text, Anthony Van Dyck's St Peter, from the baroque period, the 17th century.

What is the answer, how can we establish a vibrant culture of faith that engages with the wider secular culture without compromise and evangelises it? The answer, I believe, comes down to the way that each of us lives our daily lives. If our day-to-day activities reflect a Catholic culture then it will be stronger and more attractive than anything the secular world has to offer. This is the via pulchritudinis – The Way of Beauty - referred to recently by Pope Benedict and when we march ahead confidently on this path, we can all be the ambassadors of cultural renewal and the New Evangelisation. It is to ourselves we must look first.

What can we do so that our daily actions reflect that ‘unconscious beauty of nature’ governed by ‘the cross’ to quote Webb? The first step is the creation of an authentic culture of faith plus an education in beauty. The most powerful means of achieving both is the same. The most important educator in these respects is the liturgy. Cultural reform stems from liturgical reform.

What can we do so that our daily actions reflect that ‘unconscious beauty of nature’ governed by ‘the cross’ to quote Webb? The first step is the creation of an authentic culture of faith plus an education in beauty. The most powerful means of achieving both is the same. The most important educator in these respects is the liturgy. Cultural reform stems from liturgical reform.

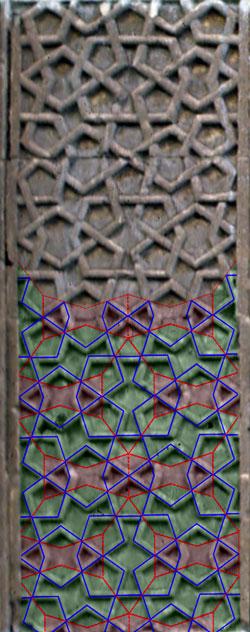

The beauty that Webb is describing is the beauty of the cosmos. The rhythms and patterns of the cosmos reveal those of the heavenly liturgy, and the earthly liturgy, which mirrors it too, is a supernatural step into this place of heavenly beauty. In developing our intuitive sense of this, the Liturgy of the Hours is so important. The Mass is a jewel in its setting, which is the Liturgy of the Hours. The Liturgy as a whole is a jewel in its setting which is the cosmos. Man’s work is an adornment to the cosmos, which can, through God’s grace, raise it up to something greater. The Liturgy of the Hours is the connecting door that both reveals more fully the beauty of the cosmos so that our work can conform to it (it ‘sanctifies our work’); and deepens for us our active participation in the sacrifice of the Mass and the Trinitarian dynamic of love that is worship of the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit.

And as Webb points out, the psalms which are at the core of the Divine Office contain this cosmic beauty. They describe it and conform to it at every level. They even describe for us the context into which they should be placed when praying them by telling us how many times a day we should pray them (seven times and once at night). When we do this, we place the psalms in an external setting that conforms to that heavenly beauty which is the pattern of the liturgical days, weeks, seasons and year; and ordering our lives to this pattern impresses upon our hearts the essence of the beauty of the cosmos which reveals to us ‘the Glory of the Lord’. I have written a number of articles that explore in greater depth the connection between liturgy, proportion, number and beauty, here.

The Liturgical Altar by Geoffrey Webb, originally published in 1936, republished by Romanitas Press, Kansans City, MO, 2010

Above, first a baroque church, of St Paul's Antwerp and second, the Banqueting House in London. An example of how the form of the Catholic Counter-Reformation became that of the wider culture, even in protestant England. Below: the opposite case, the wider culture has influenced the culture of faith in this Catholic church built in the 1950s (pre Vatican II!).

I was recently asked a question about the fact that many icons of the Annunciation portray our lady holding a scarlet or purple thread. This reflects a detail that comes from one of the apocryphal gospels the Protevangelium of James. The Catholic Encyclopedia describes it as follows: “It purports to have been written by ‘James the brother of the Lord’, i.e. the Apostle James the Less. It is based on the canonical Gospels which it expands with legendary and imaginative elements, which are sometimes puerile or fantastic. The birth, education and marriage of the Blessed Virgin are described in the first eleven chapters and these are the source of various traditions current among the faithful. They are of value in indicating the veneration paid to Mary at a very early age. For instance it is the "Protoevangelium" which first tells that Mary was the miraculous offspring of Joachim and Anna, previously childless; that when three years old the child was taken to the Temple and dedicated to its service, in fulfilment of her parents’ vow. When Mary was twelve Joseph is chosen by the high-priest as her spouse in obedience to a miraculous sign — a dove coming out of his rod and resting on his head.”

In regard to this particular detail, according to the Protevangelion when Gabriel entered Mary’s house to announce the joyous news of the Incarnation of the Logos, she was spinning purple and scarlet thread to make a veil for the temple. She was chosen because she was a virgin. Mary with this detail therefore to emphasize her virginity. If purple is shown, it signifies also her descent from the royal house of David. If Mary is shown holding scarlet thread, the colour of blood, then this signifies the fact that the Saviour took flesh and blood from her flesh and blood.

I was recently asked a question about the fact that many icons of the Annunciation portray our lady holding a scarlet or purple thread. This reflects a detail that comes from one of the apocryphal gospels the Protevangelium of James. The Catholic Encyclopedia describes it as follows: “It purports to have been written by ‘James the brother of the Lord’, i.e. the Apostle James the Less. It is based on the canonical Gospels which it expands with legendary and imaginative elements, which are sometimes puerile or fantastic. The birth, education and marriage of the Blessed Virgin are described in the first eleven chapters and these are the source of various traditions current among the faithful. They are of value in indicating the veneration paid to Mary at a very early age. For instance it is the "Protoevangelium" which first tells that Mary was the miraculous offspring of Joachim and Anna, previously childless; that when three years old the child was taken to the Temple and dedicated to its service, in fulfilment of her parents’ vow. When Mary was twelve Joseph is chosen by the high-priest as her spouse in obedience to a miraculous sign — a dove coming out of his rod and resting on his head.”

In regard to this particular detail, according to the Protevangelion when Gabriel entered Mary’s house to announce the joyous news of the Incarnation of the Logos, she was spinning purple and scarlet thread to make a veil for the temple. She was chosen because she was a virgin. Mary with this detail therefore to emphasize her virginity. If purple is shown, it signifies also her descent from the royal house of David. If Mary is shown holding scarlet thread, the colour of blood, then this signifies the fact that the Saviour took flesh and blood from her flesh and blood. The portrayal of Mary weaving began to occur about the fifth century onwards with basket and bobbin of thread. From about the ninth century onwards, the basket seems to have been omitted. The portrayal of the Annunciation in the West, seems to be less consistent in including this. I have shown a Spanish Romanesque painting that has Our Lady with thread, but not scarlet or purple. El Greco and de Champagne, in quite different styles, show a basket of cloth, but containing white material. The final image by Guido Reni has no illusion to the making of the temple veil at all that I can see.

The portrayal of Mary weaving began to occur about the fifth century onwards with basket and bobbin of thread. From about the ninth century onwards, the basket seems to have been omitted. The portrayal of the Annunciation in the West, seems to be less consistent in including this. I have shown a Spanish Romanesque painting that has Our Lady with thread, but not scarlet or purple. El Greco and de Champagne, in quite different styles, show a basket of cloth, but containing white material. The final image by Guido Reni has no illusion to the making of the temple veil at all that I can see.

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism.

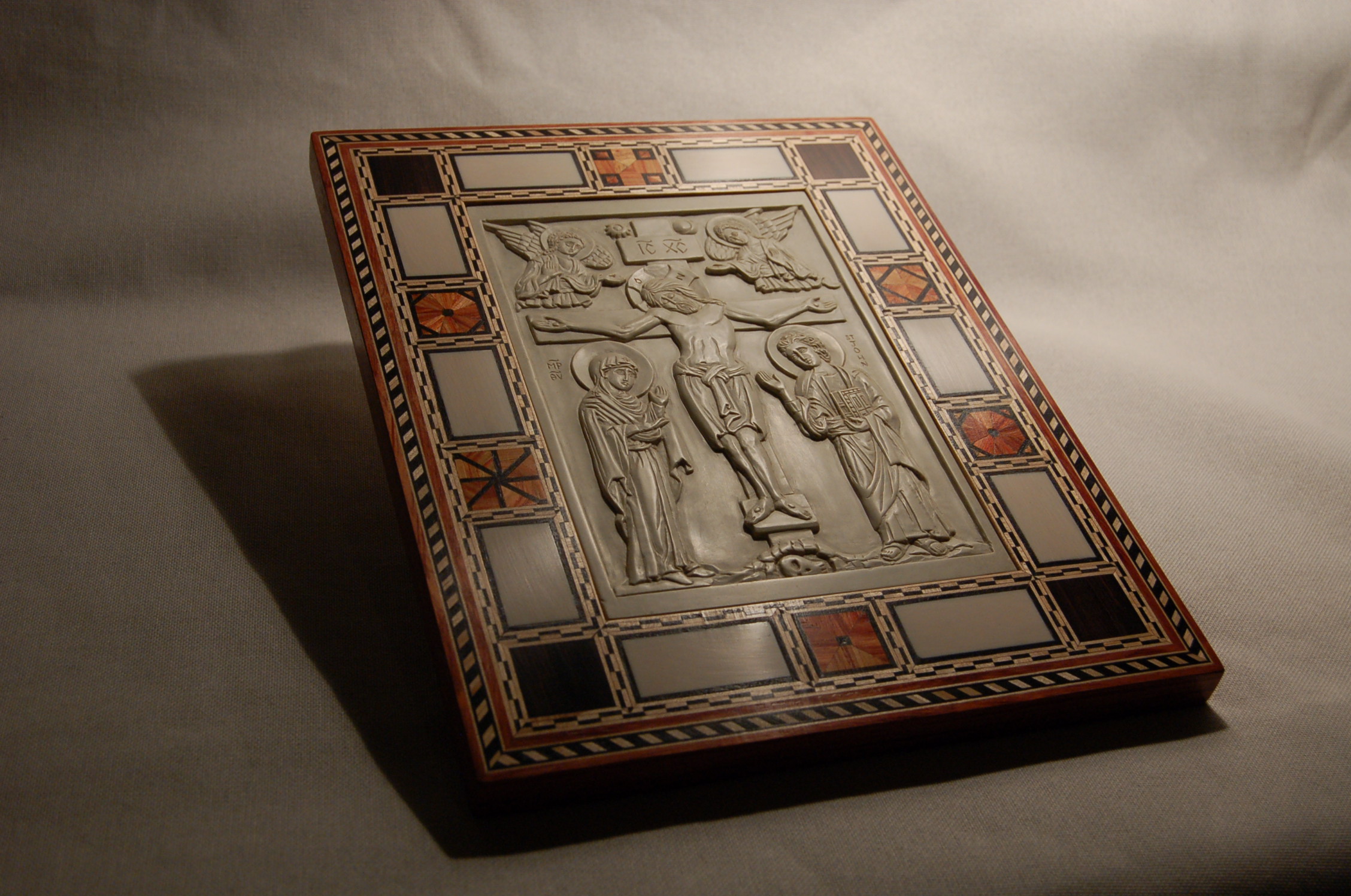

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism. Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church.

Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church. When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview. Inset into the text are examples of each. First a crucifixion from 1912 by Emile Nolde, which reflects the style of the mainstream art movement of the time. Second, left, we have a modern prayer card in which the artist, in my opinion, relies to heavily on sentiment. It is lacking an authentic Christian visual vocabulary that exists within, for example the baroque, and so is unable to communicate its message with vigour.

Inset into the text are examples of each. First a crucifixion from 1912 by Emile Nolde, which reflects the style of the mainstream art movement of the time. Second, left, we have a modern prayer card in which the artist, in my opinion, relies to heavily on sentiment. It is lacking an authentic Christian visual vocabulary that exists within, for example the baroque, and so is unable to communicate its message with vigour.