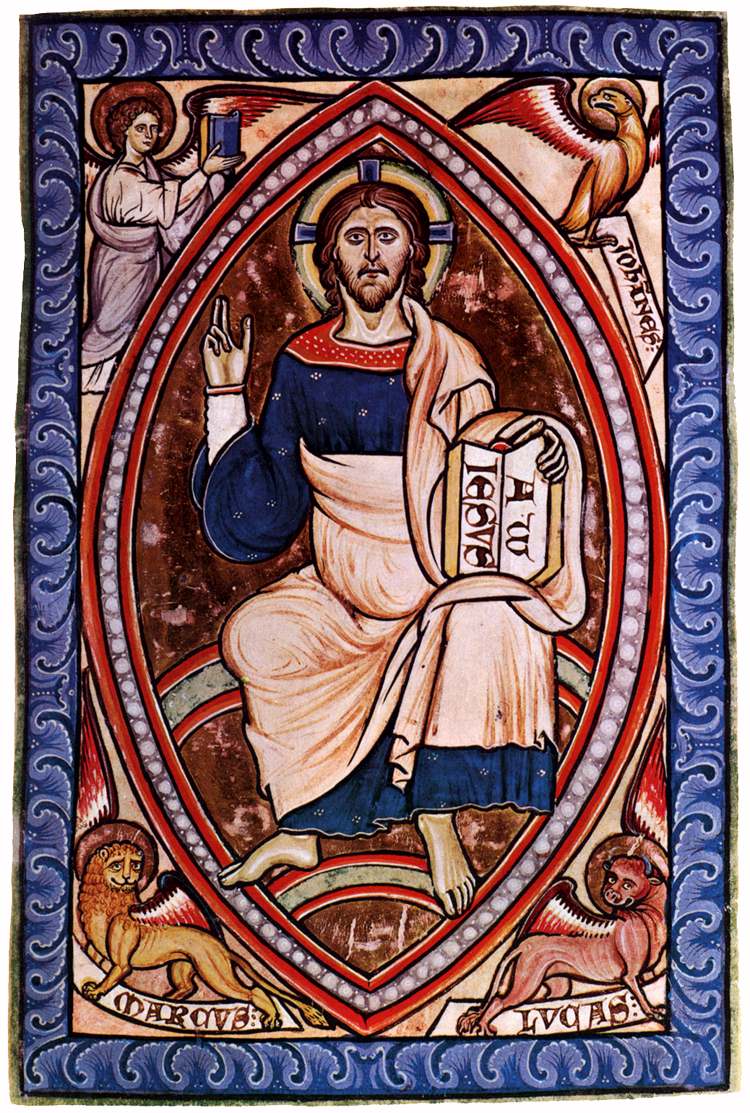

Over the summer, I read the Hymns on Paradise written by St Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem is a 4th century saint who lived in modern day Turkey and wrote in Syriac. Although much of what he wrote is liturgical - in the form of hymns, it is theologically rich. There were two reasons why I read this. The first was at the suggestion of Dr William Fahey, who told me that Ephrem described the visual appearance of Adam and Eve both before and after the Fall. This was of interest to me because in his Theology of the Body, John Paul II asked artists to portray man in the manner of Adam and Eve prior to the Fall - 'naked without shame' - in order to reveal human sexuality as gift, that is, an ordered picture of human sexuality. In order to be able to do this, I wanted to do some reasearch to see what the Church Fathers had to say on what Original Man (ie man before the Fall) looked like. In the Christian tradition, we have iconographic art which portrays mankind redeemed and in heaven (Eschatological Man), and the baroque, which shows fallen man (Historical Man) but we have no fully formed tradition in which the form and theology are integrated to portray Original Man and so no visual vocabulary to draw on in order to paint him.

The desire to read him was reinforced recently on my trip to Spain, when I read Pope Benedict's Wednesday address on St Ephrem, a Doctor of the Church, as part of my own personal 'Office of Readings' in the morning (I have written about this here). In this Benedict tells us that St Ephrem is 'still absolutely timely for the life of the various Christian churches...a theologian who reflects poetically on the basis of Holy Scripture, on the mystery of man's redemption brought about by Christ, the Word of God incarnate'.

Over the summer, I read the Hymns on Paradise written by St Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem is a 4th century saint who lived in modern day Turkey and wrote in Syriac. Although much of what he wrote is liturgical - in the form of hymns, it is theologically rich. There were two reasons why I read this. The first was at the suggestion of Dr William Fahey, who told me that Ephrem described the visual appearance of Adam and Eve both before and after the Fall. This was of interest to me because in his Theology of the Body, John Paul II asked artists to portray man in the manner of Adam and Eve prior to the Fall - 'naked without shame' - in order to reveal human sexuality as gift, that is, an ordered picture of human sexuality. In order to be able to do this, I wanted to do some reasearch to see what the Church Fathers had to say on what Original Man (ie man before the Fall) looked like. In the Christian tradition, we have iconographic art which portrays mankind redeemed and in heaven (Eschatological Man), and the baroque, which shows fallen man (Historical Man) but we have no fully formed tradition in which the form and theology are integrated to portray Original Man and so no visual vocabulary to draw on in order to paint him.

The desire to read him was reinforced recently on my trip to Spain, when I read Pope Benedict's Wednesday address on St Ephrem, a Doctor of the Church, as part of my own personal 'Office of Readings' in the morning (I have written about this here). In this Benedict tells us that St Ephrem is 'still absolutely timely for the life of the various Christian churches...a theologian who reflects poetically on the basis of Holy Scripture, on the mystery of man's redemption brought about by Christ, the Word of God incarnate'.

As Dr Fahey had indicated, there is much useful material written by St Ephrem on Original Man and I am in the process of pulling this together for a longer article. So in this respect, St Ephrem is certainly timely.

I'm sure the style of the translation had a lot to do with this as well (by Sebastian Brock), but I found him pleasurable as well as interesting reading. He was a prolific writer and so there's plenty more to look at in the future!

My reason for bringing all of this up here is that St Ephrem wrote something that caught my eye for another reason in the 9th of his Hymns to Paradise:

Far more glorious than the body is the soul, and more glorious still than the soul is the spirit, but more hidden than the spirit is the Godhead.

At the end, the body will put on the beauty of the soul, the soul will put on that of the spirit, while the spirit shall put on the very likeness of God's majesty.

For bodies shall be raised to the level of souls, and the soul to that of the spirit, while the spirit shall be raised to height of God's majesty.

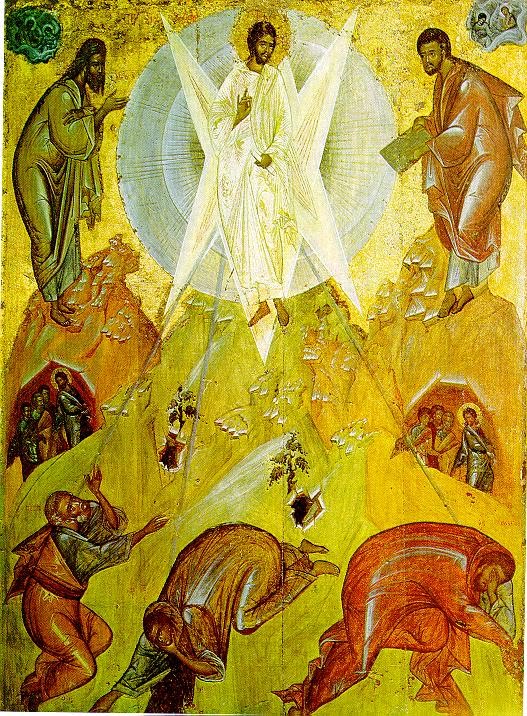

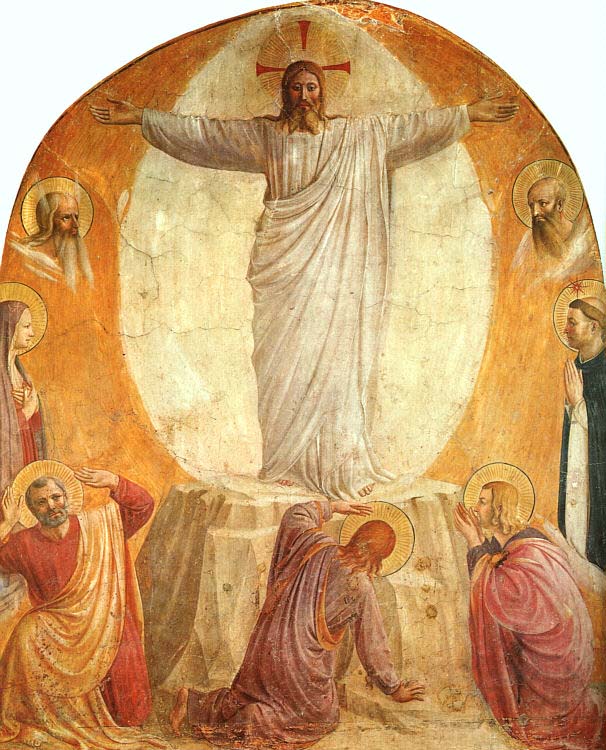

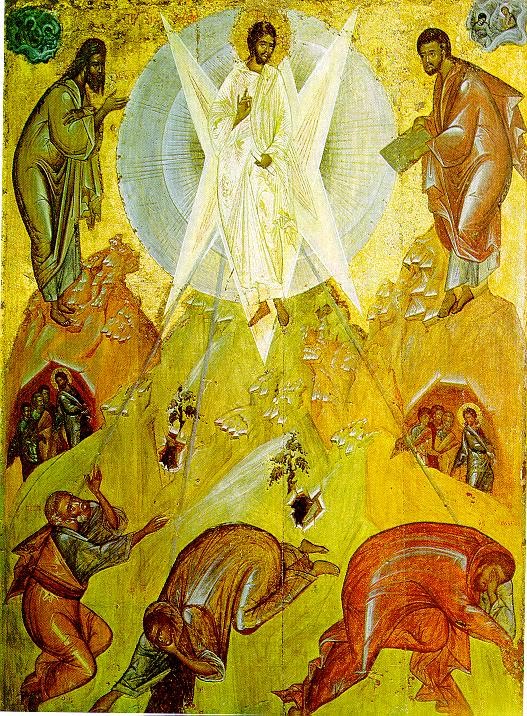

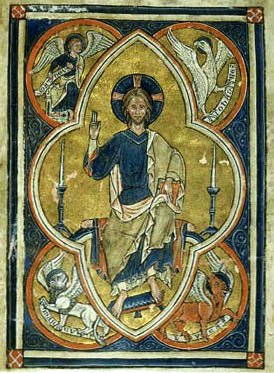

This describes so well what Jean Corbon described as the transformation that happens to us when we are full participants in the liturgy, as described here. The icon of the transfiguration is an icon of the liturgy, he says, for we participate in Christ's transfiguration when we participate in the liturgy. This passage from St Ephrem suggests that the spirit is a special place in us that is in primary contact with God's majesty that is itself raised to God's majesty and is transfigured. This indicates a special place therefore for the spirit in our participation in the liturgy, for the liturgy is the way in which we ascend, by degrees in this life, to union with God which is complete, as St Ephrem puts it 'at the end' in paradise. It also reinforces an idea that Stratford Caldecot described in his essay, Towards a Liturgical Anthropology. Strat suggests that a lack of full acknowledgement of the spirit as the higher part of the soul has lead, in part, to an incomplete participation in the liturgy since the 19th century at least, and in turn has lead to the Catholic cultural decline that we are all so well aware of.

In another papal address, on St Gregory of Nyssa, Pope Benedict XVI himself referred to this anthropolgy of body, soul and spirit as being part of the tradition of the Church.

To summarise how the spirit relates to the soul here's my understanding: the spirit is the highest part of the soul. It is that part of the soul which touches on God, a portal for the grace that pours out from God 'transfiguring' us into the image and the likeness of God. The divinely created order of the human person is the spirit, which is closest to God, rules the rest of the soul which in turn rules the body. All move together in union and communion with God.