Can elevator music be elevating...or is it just superficial fluff peculiar to our age?

What makes easy listening at once so popular and yet so reviled by ever self-respecting and serious music fan? I thought about this recently when my wife, who is Venezuelan, put on a CD in the car by a Mexican artist called Rocio Durcal (you can hear her at the bottom of this article). I had never heard of her or the music before (she was a Mexican singer) but enjoyed it, and it struck me that at one time I would never have admitted it, for with its gushing strings and romantic themes this was definitely, dare I say it....easy listening.

Can elevator music be elevating...or is it just superficial fluff peculiar to our age?

What makes easy listening at once so popular and yet so reviled by ever self-respecting and serious music fan? I thought about this recently when my wife, who is Venezuelan, put on a CD in the car by a Mexican artist called Rocio Durcal (you can hear her at the bottom of this article). I had never heard of her or the music before (she was a Mexican singer) but enjoyed it, and it struck me that at one time I would never have admitted it, for with its gushing strings and romantic themes this was definitely, dare I say it....easy listening.

When I was 18 and took music seriously, and I mean really seriously, you defined the sort of person you were by the music you liked. This was in the days of large vinyl LPs with brightly coloured covers and so I always made sure that I would be seen carrying the socially acceptable record covers around the school campus. I was a serious 'progressive' rock fan branching out into jazz rock/fusion and used to love quoting band names that I thought you hadn't heard of such as Brand x (Phil Collins's part-time jazz rock band), Bruford (the former Yes drummer's jazz rock band) and Return to Forever featuring Chic Corea on keyboards, Stanley Clarke on bass and Al Dimeola on guitar.

I had long hair (or as long as I could have it without getting into trouble at school), flared jeans and embroidered motifs of my favorite band on my denim jacket. If you had no clue who the people I referred to were, or had never heard the music, that was great. Half the attraction was that they didn't have mass appeal - or only appealed to the right sort of person. We were teenage musical gnostics with elite sensibilities and eclectic tastes that we though only the adolescent cogniscienti would understand.

If any artist was too popular or popular with anyone other than the right sort, I would like them less. I remember taking delight in the BBC using instrumental sections from Genesis's The Musical Box as background music for a news magazine feature on Pope John Paul II's visit to Ireland in 1979. What made it perfect for me was that while the BBC producers obviously knew this music, very few watching the TV program would know what they were listening to. Here was validation of my tastes from the culturati of the country.

For the curious, here's And So to F... by Brand X featuring Phil Collins on drums. He is playing some obscure rhythm...the comments in YouTube tell me nine beats in a bar. Collins played with this band while with Genesis, but before he made it as a solo star:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tOLmTsZ0YSw

At my high school, an all boys school, we were divided into two musical camps. I was with those who liked the sort of rock music that had pretensions to being the classical music of its day. The other followed the newly arrived punk scene which claimed to signify rebellion and anarchy which, so it was said, was 'what rock'n'roll was meant to do'. I remember one dissenter, Bill Bland, who used to listen to soul, jazz and reggae - Isaac Hayes, Miles Davis and Steel Pulse (UB40 were too mainstream!). Rest of us didn't know what to make of him.

For the fact that we argued about the merits of the Sex Pistols and Stranglers, both camps were clear on one thing, easy listening was the lowest of the low. Saying you liked Andrew Lloyd Webber or Julio Iglesias was just about social suicide in anybody's book. The greatest put downs for any music were to brand it as Easy Listening and, even worse, West Coast (Californians who thought they were cool and knew how to rock but didn't really know their stuff).

Sometime in the early 1980s I heard an interview with Phil Collins. He was saying that one of his favourite artists was a singer called Stephen Bishop. I had never heard of him and immediately ran out to buy an album. I bought Careless. The cover was a little off-putting - a fuzzy focus photo pretty man with a bouffant hair style. On listening to it, I just couldn't believe it. It was a load of soppy sentimental love songs. I felt betrayed. Here was a serious rock musician, a virtuoso drummer like Phil Collins who could play jazz and fusion recommending something that, dare I say it, my mum might even listen to. What was worse, he was from San Diego, so he was both Easy Listening and West Coast.

Here is a tune by Bishop, called Looking for the Right One see what you think:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=croQAwuEhnU

After initially rejecting him, I caught myself humming the tunes one day. So I played it more and more and though I wasn't telling anyone at this stage, gradually I collected every record he had ever released. When Phil Collins started to sell his solo records, I was initially disdainful, and then realised that there was much of Stephen Bishop in what he was doing. He even appeared on later Bishop albums, from which the following is taken:

Stephen Bishop, Parked Cars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hF82ya4b924&feature=kp

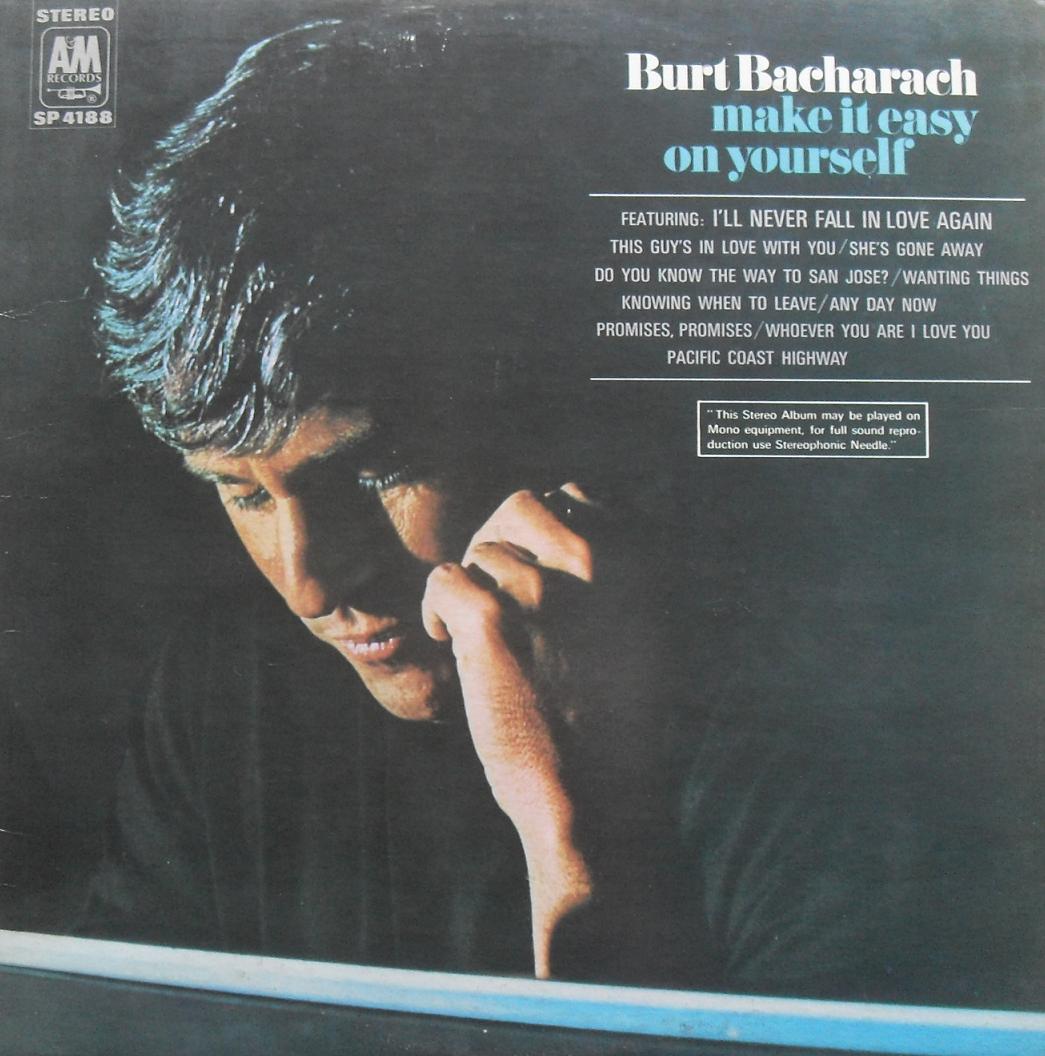

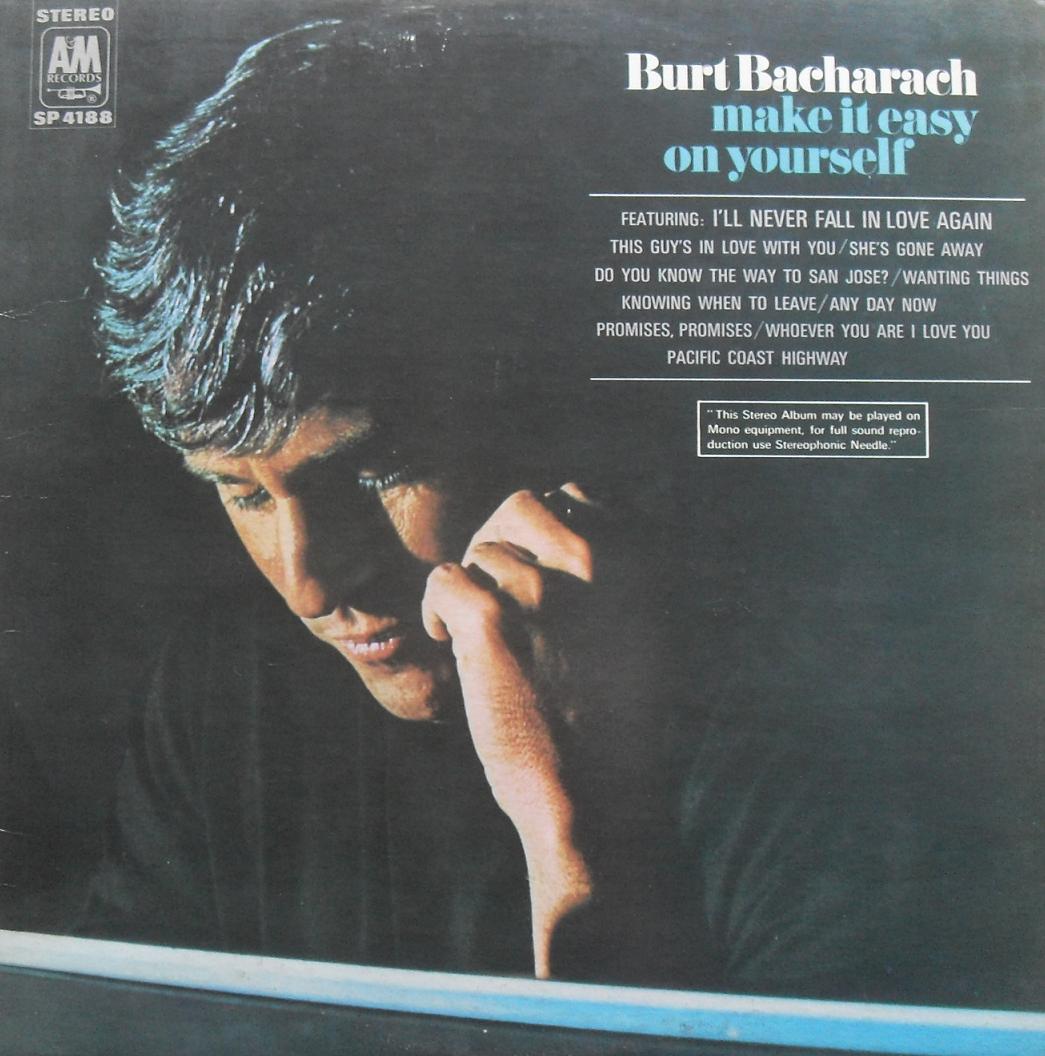

Furthermore, later once I had overcome that barrier of pride and could acknowledge that I liked it, I found myself buying and listening to others, Burt Bacharach and Herb Alpert are two examples given here below.

So what is the place in a culture of beauty for such music. In the context of pop music it is musically sophisticated and created skillfully to appeal to have an immediate impact on a broad range of people with little effort on the part of the listener...hence the name. It is melodic, well crafted and well performed and I can't help liking it.

I still play it and sing along when I'm on my own in the car. But is it bad for me? Has Stephen Bishop beguiled me and corrupted my sensibilities? Is it detrimental to the soul? Am I, to quote the title of a song by Australian rock band AC/DC, on a 'highway to hell' as I sit behind the steering wheel of my Toyota Corolla singing along to what my ishuffle feeds the audio system?

I suggest that musically, while not the most complex or profound and even at its best it is unlikely ever to cause a dramatic conversion to the Faith. This is a genre that is not intrinsically bad. Having said that, if this was the sum total of my listening, then it might be problematic, but having an occasional sing-along in the car is fun every now and again. The light-hearted and romantic have their place provided that they sit happily within a broad range of music. I have a feeling that this will horrify the every-went-downhill-after-Bach school of musical appreciation, but I don't think I can spend the whole time on just chant and polyphone, even though I would support the idea strongly that this is the highest form of music.

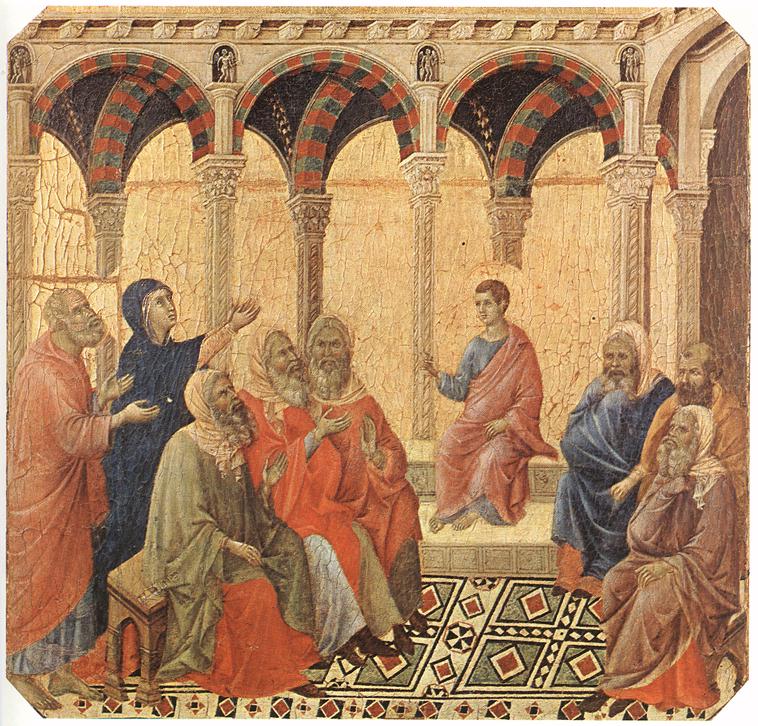

As with all popular forms of music, I think that the Christian must look at it and think about what makes it popular. At its root it must be something good. No matter how noble and accessible the music of the liturgy or serious classical music or whatever its High Culture equivalent of the time, there will always be a place, I suggest, in the mass culture for something that is less demanding. In the middle ages there was folk music and the romantic, sometimes more serious, chivalric poetry, the songs of the jongleurs and the troubadors. Some of this was high culture, but not all. If we don't create good easy listening, then bad easy listening will dominate

As for anything that is so enduringly popular, the question is not one of replacing something we deem to be less than perfect, but rather one of asking how we can add to it - modifying and improving, even enobling. Yes the superficial can be noble. It can be the form that stimulates gently the desire for the good and leads us to something greater. It may only be skin deep, but the perfect body has perfect skin too!

The sentiments expressed in the words of our modern form are not always morally sound and I would prefer that it was better in this respect (this was true of the medieval counterparts also, I understand). The poetry of the lyrics could be improved but let this be a challenge to Christian song writers. Musically, the form should be considered too - does it open the door to higher musical forms or distract from them? I can envisage the day when a new Barry Manilow attracts adoring housewives and men who listen but won't admit it publicly (like me) to the world of Beauty, Truth and Goodness.

This creates another litmus text for the establishment of a true Christian culture. We aim for the time when even the elevator music is elevating.

Burt Bacharach, Dionne Warwick, Walk on By

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0wCuwUneSM

Herb Alpert and his Tijuana Brass epitomises the Latin easy listening style for me. I was shocked to discover recently that he is ethnically Ukrainian, not Hispanic. In fact none of his band were hispanic.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_KDPUTyDyQ

And here's the tune that started the whole reflection, Rocio Durcal sings Amor Eterno:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBWaxCIwz_M

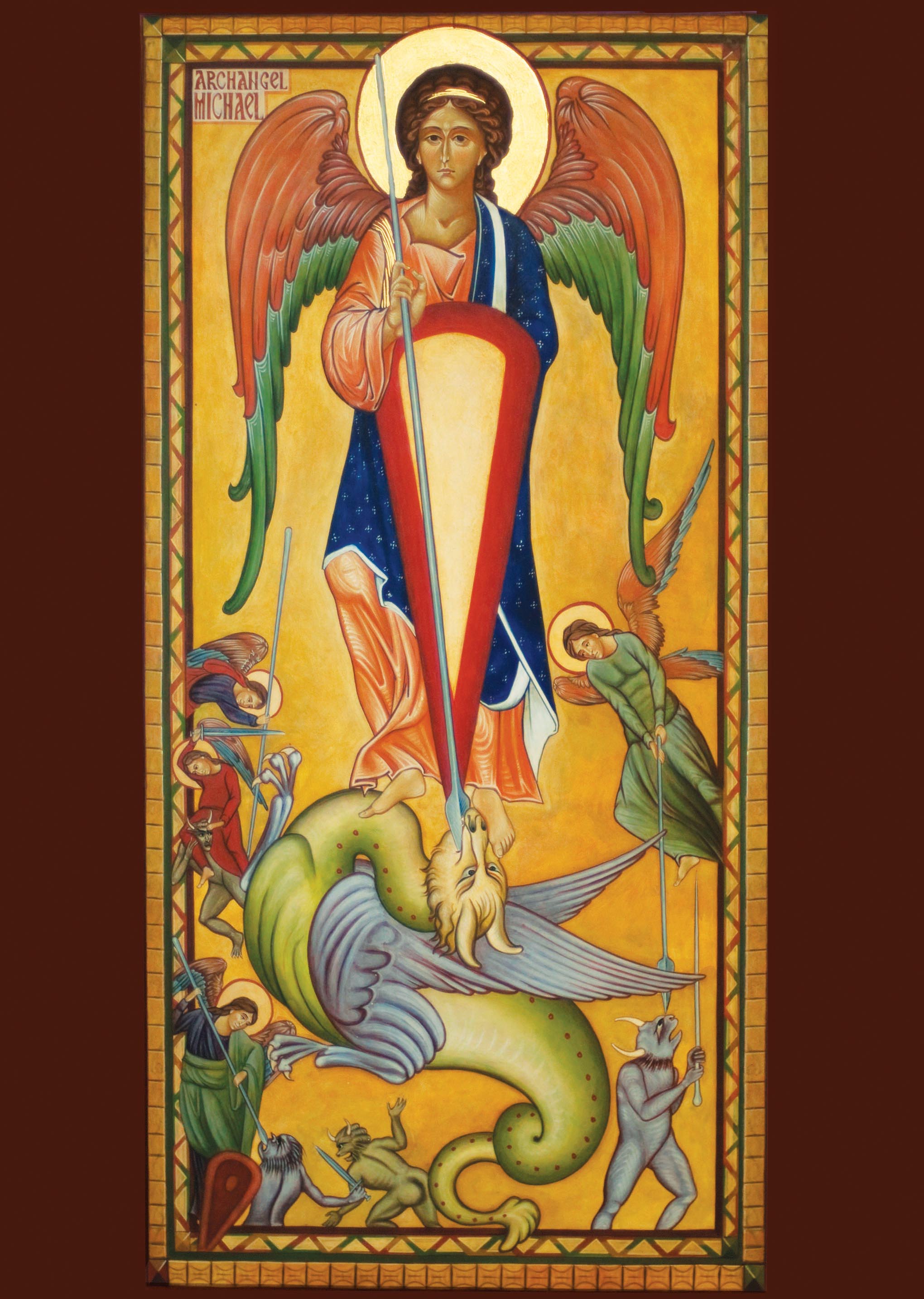

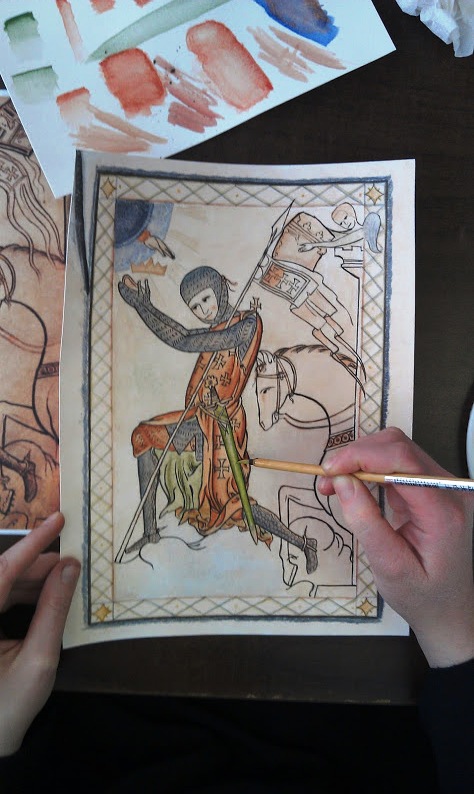

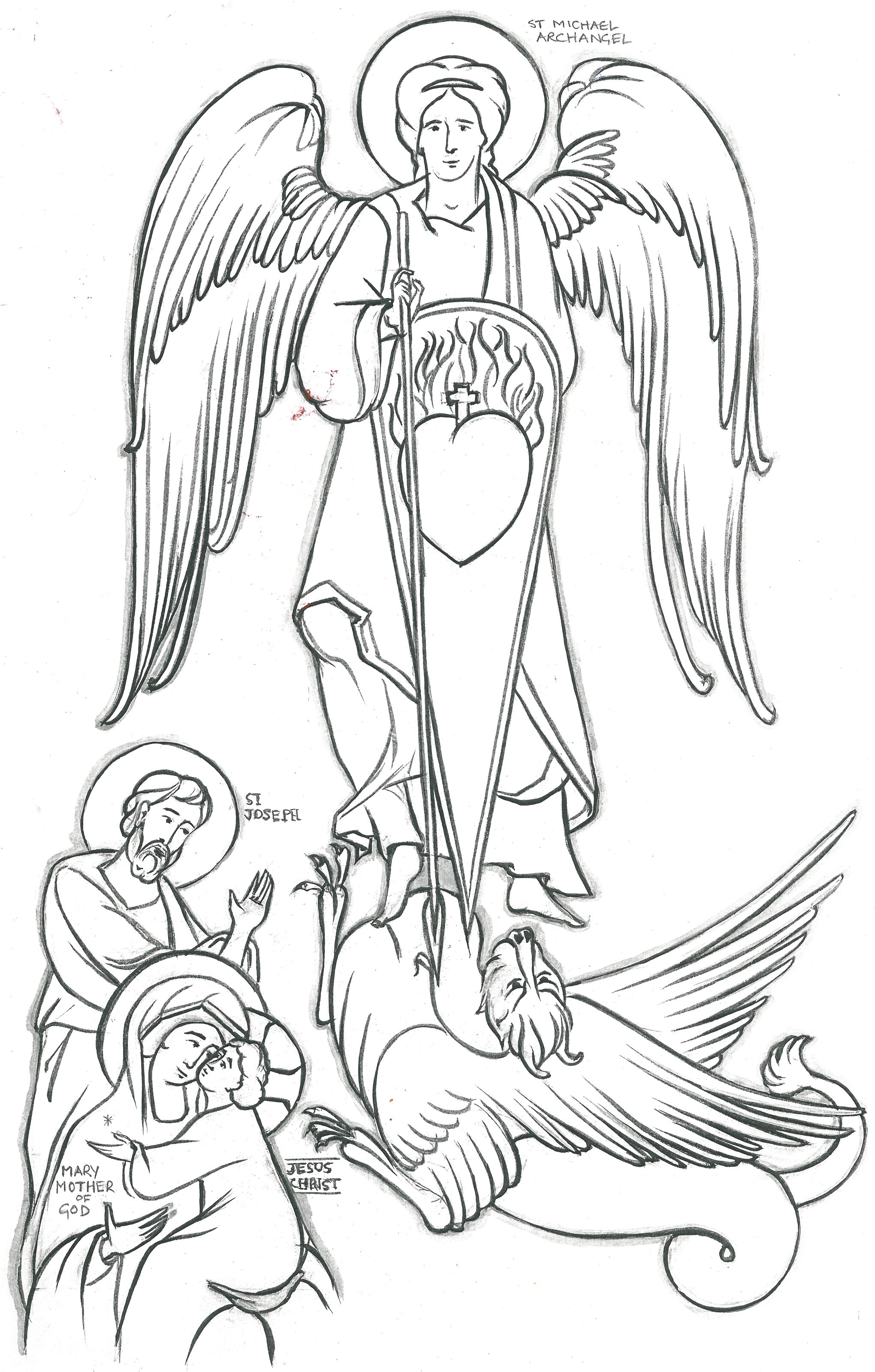

Colouring pages from the Sophia Institute Press website. There are two styles: iconographic and 13th century English gothic from the School of St Albans.

I am often asked by parents and teachers of young children how we can develop their artistic sensibilities. I always suggest that part of it is exposing the to traditional styles of art as early as possible. Unless you have ready access to big city art galleries, or are able to own your own originals, which most don't, the most simple way is for them to see good reproductions. The task then is to make them interesting. So any book that I buy for my little daughter, I try as far as possible not only to buy books with beautiful illustrations, but also those done in traditional styles. Clearly you can't get obsessive about this...I just do it where I can.

Colouring pages from the Sophia Institute Press website. There are two styles: iconographic and 13th century English gothic from the School of St Albans.

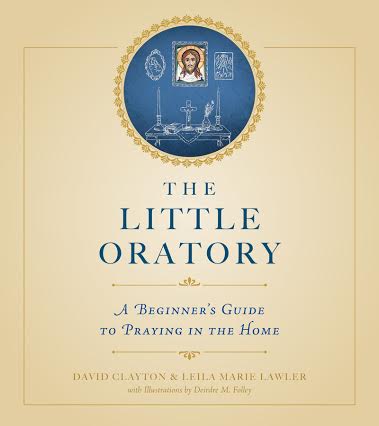

I am often asked by parents and teachers of young children how we can develop their artistic sensibilities. I always suggest that part of it is exposing the to traditional styles of art as early as possible. Unless you have ready access to big city art galleries, or are able to own your own originals, which most don't, the most simple way is for them to see good reproductions. The task then is to make them interesting. So any book that I buy for my little daughter, I try as far as possible not only to buy books with beautiful illustrations, but also those done in traditional styles. Clearly you can't get obsessive about this...I just do it where I can. The new book, The Little Oratory: The Beginner's Guide to Family Prayer contains lots of icons in colour, which can be removed and used to create an icon corner; and also every chapter opens with a facing page that is a line drawing of an icon and pertains to the chapter in question. The intention was that, as well as elucidating the points discussed in the chapter, that leads to greater understand of both text and image, this could be photocopied and used as a teaching resource for children.

The new book, The Little Oratory: The Beginner's Guide to Family Prayer contains lots of icons in colour, which can be removed and used to create an icon corner; and also every chapter opens with a facing page that is a line drawing of an icon and pertains to the chapter in question. The intention was that, as well as elucidating the points discussed in the chapter, that leads to greater understand of both text and image, this could be photocopied and used as a teaching resource for children.