The choice of music at Mass matters to me. It was hearing polyphony and chant done well that contributed to my conversion. It was hearing practically every other style of music in church that contributed to my not becoming a Christian until I did.

The choice of music at Mass matters to me. It was hearing polyphony and chant done well that contributed to my conversion. It was hearing practically every other style of music in church that contributed to my not becoming a Christian until I did.

I grew up hearing Methodist hymns in church, and today I can’t bear to sing them or any other “traditional” 19th century-style hymn, even if the words are written by Fr Faber. I hate Christmas carols and find them sentimental. I had grown tired of Silent Night and Ding Dong Merrily on High before I was 10 years old, and today always refuse to go caroling in the neighborhood on the grounds that I don’t want to chase any more people away from the Church.

I find the attempts to be musically current in church even more repellent. Whether it’s the Woodstock-throwback-with-added-sugar of the standard pew missalet, candied Cat Stevens presented by a cantor in a faux operatic or broadway-musical style, or the more recent equivalents, imitations of the pop music of the moment to “get the young people in,” it’s all the same to me. If ever there was an award that labels a musical artist as a legend in his own lunchtime, it’s “Christian album of the year.” Attempts at being Christian and cutting edge always seem outdated five minutes after they were composed, and most weren’t that great for the four minutes they were relevant.

Whenever I am in church and expected to sing along to such inventions, I shift uneasily and look down at the ground, hoping nobody notices I’m not joining in. (That’s assuming I can hit the pitch, which is usually too high for most men anyway.) It is an attempt to appeal to young people that feels to me like an imitation of the foolish parent who tries to hard to be liked by his adolescent children by adopting inappropriate teenage fashions; he inevitably misses the mark, and loses self respect and the respect of the younger generation in the process. To my mind, there’s nothing more embarrassing than a grown-up trying to be hip and groovy when the words “hip” and “groovy” haven’t been hip and groovy for a long, long time. I thought that when I was 13-year-old atheist and I still think it today.

And I’m not just talking about the music for the Novus Ordo or the Masses in the vernacular. I am amazed at how often I struggle at the choice of hymns and the sentimental Masses from the 19th or early 20th century that some choir masters seem manage to dig up when given the freedom to choose music for the Extraordinary Form. Where do they get them from?

All of this music drives me to distraction; and before I heard chant and polyphony and found out there was something different, it drove me to atheism too.

Am I am unusually narrow minded and intolerant in regard to music? Well, in the context of the liturgy. I am very likely spoiled by having had the benefits of the choirs of the London Oratory and Westminster Cathedral, or occasionally Anglican chant at Choral Evensong at one of the great Anglican cathedrals in England.

But I should point out that as long as I can remember, and long before I converted, my gut reaction told me that contemporary styles of Christian music were just the epitomy of “naffness,” to use the English colloquialism. Even when I was a schoolboy in Birkenhead, the bad musical taste of Christians gave me plenty of ammunition for deriding them for trying to be trendy when they “didn’t have a clue.”

Furthermore, I don’t think I am overly traditional or reactionary about music in other contexts. I don’t believe that it all went downhill after Bach, for example, or with Wagner (the Siegfried Idyll is one of my favourite pieces). I enjoy operas, swing, jazz, and pop music. I play Appalachian Old Time on my banjo (very badly, and if you’re interested, my favorite Old Time tune is called Waiting for Nancy.) I sing the pop songs from my past when I’m driving and think nobody is listening - Stephen Bishop’s sentimental love songs, Rory Gallagher’s Wayward Child, Betty Boo’s Where Are You Baby or Stereo MCs’ Connected. (I lost touch with the pop world after 1992).

But I have never thought that any of this was music for the liturgy.

For a long time after my conversion, if I couldn’t get to the Oratory, I would seek out a spoken, low Mass. If I visited a church for the first time, I picked an early morning Mass in the hope that the parish didn’t have the resources to put on any music that early. But even then I found that it’s not unusual for the 7:30 am to have a troop of local schoolchildren doing a hand-bell version of Immaculate Mary for the Offertory. I don’t think I am alone in this.

Although the others in attendance will probably not have exactly my taste in music, there will be many who are as strong in their likes and dislikes as I am, and will most probably dislike the music at Mass as much as me.

I would maintain that it is the music at Masses that has contributed as much to the the drop off in the numbers attending as any other factor. Putting aside those who attend the rare parishes that offer predominantly chant and classic polyphony, for the most part the only people left in the pews of most churches are the tone deaf, those who have sufficient faith to offer up the pain of listening to music they hate, or the very small number of people who actually like what they hear.

Whenever I bring this up with priests, their concern is for those who currently go to Mass. The priest will tell me that for “pastoral” reasons, he has to be careful about changing things, as he doesn’t want to offend people and drive them away. This is an understandable reaction, but my thought when I hear this is that for every person who is enjoying the music in Mass, there are a ninety-nine more who don’t like it, and most of these 99 people don’t come to church at all, and won’t as long as the music stays as it is. I always want to ask the question: when are we going to start being pastoral to the 99% outside the church and stop pandering to the 1% (if I can borrow a slogan from elsewhere!)

But even if there is a desire to create attractive music? What music should we choose?

Perhaps we could just cut out all modern forms and stick exclusively to chant and polyphony? Unlike all the other styles mentioned above, we can say objectively, regardless of personal taste, that according to the tradition of the Church these styles are appropriate for the liturgy.

I think therefore a switch to chant and polyphony across parishes would help and attendance at Mass would increase a little bit, after an initial drop. Some people will respond to it immediately, and others will grow to like it. But I don’t think this measure alone would be enough. Not everyone will persist in developing that taste unless there is other music that can be accessible to them, and lead them into an appreciation of the canon of great works.

This has been pointed out by popes in the past. While asserting the centrality of chant and polyphony, Popes such as Pius X and Pius XII have also acknowledged the need for new compositions in the liturgy. For example in Mediator Dei, Pius XII wrote:

'It cannot be said that modem music and singing should be entirely excluded from Catholic worship. For, if they are not profane nor unbecoming to the sacredness of the place and function, and do not spring from a desire of achieving extraordinary and unusual effects, then our churches must admit them since they can contribute in no small way to the splendor of the sacred ceremonies, can lift the mind to higher things and foster true devotion of soul.'

The necessity of accessible contemporary forms as well as the canon of traditional works is the message of Benedict XVI’s book, A New Song for the Lord; Faith and Christ and Liturgy Today. And he places the responsibility for making it happen on the artist or composer, telling us that it is the mark of true creativity that an artist or composer can “break out of the esoteric circle” – i.e., the circle of their friends at dinner parties – and connect with “the many.”

This grave responsibility is one that thus far, it seems to me, the vast majority of Christian artists in almost every creative discipline have not been able to take on. That is not to say, however, that the task facing creative artists today is easy. Indeed, it may be so hard than it needs an inspired genius in any particular field to show us the way before it can happen.

One thing is clear to me: we need a fresh approach. And contrary to what many seem to think, most music in churches today is not broadly popular. It is strongly disliked.

Dr Peter Kwasniewski recently wrote a very good piece for the blog OnePeterFive, highlighting the difficulties in adapting modern forms of Western music to music appropriate to the liturgy. He and I both think that what has been done in the last 50 years particularly has been largely disastrous. He doubted that it could ever be done because of the special nature of modern culture. I agree that it is difficult, but for all that the style of modern music speaks of the secular world, I am a little more optimistic than him. The task is difficult certainly, but I hold out hope and argue that just because it has been done badly up until now, it doesn’t mean that it can’t be done well in the future.

Here is one particular difficulty that composers are going to have to overcome if they are to engage with modern culture successfully (and prove me right!). This arises from the fragmented nature of modern culture.

Contrary to what I have heard many say, I don’t believe the general population today is musically ignorant and uncultured. Modern society is highly musical and has sophisticated taste. More people enjoy music and have access to a greater range of styles from all periods than ever before, and they are choosing what appeals most. Most people are not ignorant, for example, of what classical music is, even if they have only heard it in a film score. The problem is that this sophistication is one that fragments rather than unifies. People today know what they like and dislike, and they are sensitive to even subtle changes in style, and will react strongly to them. Within any genre, there are myriad sub-genres that are discernible to devotees and who discriminate between them. And even within the same sub-genre, people will strongly favor one artist, but react strongly against another; hence the cliché that those who like the Beatles hate the Stones. (I am a Beatles person, by the way). This sophisticated level of discrimination exists in every genre of popular music up to the present day. Furthermore, the scene changes rapidly. What was popular with teenagers a few months ago is now forgotten. And at any moment, what is popular with teenagers is not liked generally by the rest of the population.

As a result, there is no form of secular music that I know of, classical or contemporary, that currently exists and will appeal to all people. This is why choir directors should not blamed so much for introducing music that is so disliked. Given the compositions available to them, it is almost inevitable that their choices will be disliked by most people. (Where criticism is fair, I think, is where the choice of these modern forms supplants, rather sits alongside, traditional chant and polyphony.)

So, although virtually nobody will share my tastes in music, there will be very many people, I suggest, who are like me in having a strong sense of what they like and dislike, and because they are used to being able to choose the music they listen to, very little tolerance for what they don’t like, however unrefined that taste may seem to others. This is why, as one newly appointed choir director described to me, a parishioner approached him and told him that he was worried that the music at the church would change because he was “very traditional.” “Oh, that’s good,” said the choir director, “I’m pretty traditional too.” “I’m so glad,” said the parishioner, with obvious relief, “so we’ll still have the music we’ve always had, especially my favorite traditional tune, On Eagles Wings.”

So we can see why, in my opinion, any musical form composed for the liturgy that is obviously derived from any contemporary music style or past style that has not transcended its own time (and I would put all the commonly sung hymns into this category) will almost certainly be disliked by the majority.

Therefore, we need a fresh approach. This, I suggest, will be radically different from the superficial analysis that has produced “contemporary” Christian music. Musicologists will have to get deeper into the embedded code that unites the forms of modern music together, build on what is good, reject what is bad, and incorporate these into the essential patterns of interrelated harmonies and intervals in a form that also satisfies the essential and universal criteria of liturgical music. If these are played in church alongside chant and polyphony, the appropriateness of such music will become apparent even to many who do not consider themselves music experts. To the degree that a composer is successful, the new compositions will not only connect with people today, but will transcend their own time, with the best examples being added to cannon of great works.

If I am wrong, and however penetratingly we search for it, this common code of modernity that is essentially good does not exist, then Peter is right! There is a reason for my optimism, however, for I do see some modern compositions that do seem to me to be accessible to more people, and which are appropriate for the liturgy.

Some of the very best of these examples (although not all by all means) seem to occur in works composed for the vernacular. It seems that seeking the principles that connect music to language at the most basic level, forces composers into that territory where they are beginning, at least, to access a common code for the culture, which today springs from the vernacular. Those that do so in such a way that they respect also what is essential to chant and polyphony, create the beginnings of this crossover music. I have noticed also that modern composers look with some success to Anglican and Eastern forms of chant for inspiration. The result is successful when it seems both of our time, and of all time. Some of the people who come to mind immediately who are doing this are Adam Bartlett, with his material available through Illuminare Publications, Fr Dawid Kusz OP at the Dominican Liturgical Center in Krakow (who composes for the Polish language), Paul Jernberg, Roman Hurko, Adam Wood, Frank LaRocca and our own Peter K. There are more I am sure. What is interesting to me is that the successes in the vernacular can then feed back into composition for Latin. Paul Jernberg composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the English Novus Ordo. It was so admired by one patron that he commissioned Paul to write a setting for Ecce Panis Angelorum and he has also composed for the Latin Ordinary - appropriate of course for both OF and EF.

I do not know for certain if all, or indeed any of these composers are the trailblazers to whom the future will look back, as we today look back to Palestrina. Only time will tell. But I do feel sure that theirs is the type of approach that we should be aiming for, and is the one that will succeed in the end.

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

The nature of the dividing line between sanctuary and nave in a church has been a hot topic over the years. I raise the subject today not to spill yet more ink in complaining about the removal of altar rails in churches over the last 50 years or so, although it is something I do feel strongly about. Rather, I am interested in trying to establish how, with due regard for tradition, we might encourage in the Roman Rite a renewed engagement with art in the liturgy, in the such a way that it deepens our participation, rather than distracts from it.

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

The nature of the dividing line between sanctuary and nave in a church has been a hot topic over the years. I raise the subject today not to spill yet more ink in complaining about the removal of altar rails in churches over the last 50 years or so, although it is something I do feel strongly about. Rather, I am interested in trying to establish how, with due regard for tradition, we might encourage in the Roman Rite a renewed engagement with art in the liturgy, in the such a way that it deepens our participation, rather than distracts from it.

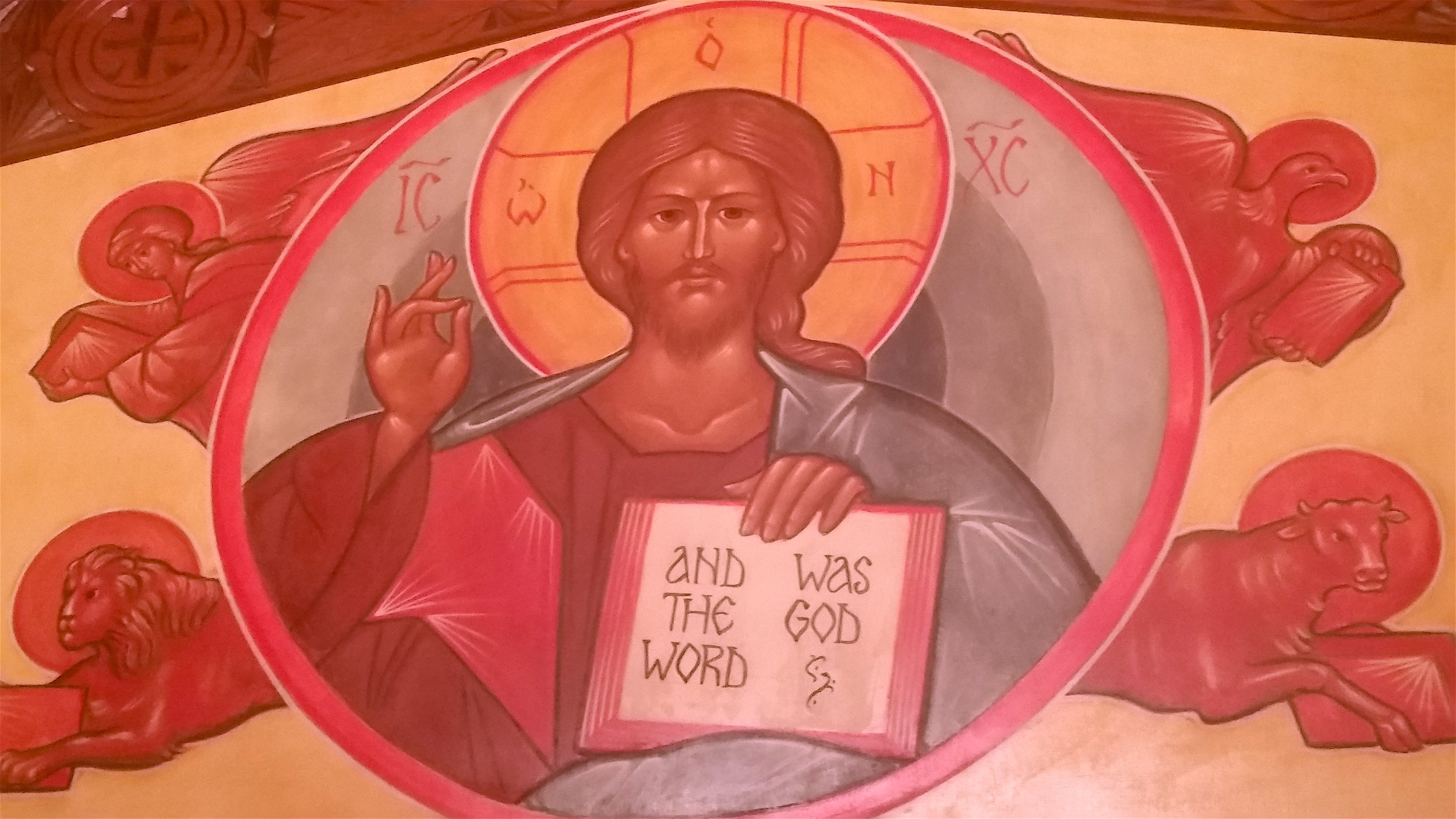

The Melkite Rite, which has its origins in the Middle East, is one of the Byzantine rites of the Catholic Church. The traditions of the Melkite Church reach back to Apostolic times, and bear eloquent witness to the harmonious interplay between Catholic liturgy and the culture of the region in which that liturgy developed.

The Melkite Rite, which has its origins in the Middle East, is one of the Byzantine rites of the Catholic Church. The traditions of the Melkite Church reach back to Apostolic times, and bear eloquent witness to the harmonious interplay between Catholic liturgy and the culture of the region in which that liturgy developed.

Here is an article by my friend, Keri, who is an icon painter and teacher. I am delighted that she will be teaching courses at Pontifex.University in the coming months. Keri writes:

Here is an article by my friend, Keri, who is an icon painter and teacher. I am delighted that she will be teaching courses at Pontifex.University in the coming months. Keri writes:

Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog,

Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog,

These seven liberal arts and the artists who most exemplify them are featured on the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral. (Geometry: Euclid, Rhetoric: Cicero, Dialectic: Aristotle, Arithmetic: Boethius, Astronomy: Ptolemy, Grammar: either Donatus or Priscian)

These seven liberal arts and the artists who most exemplify them are featured on the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral. (Geometry: Euclid, Rhetoric: Cicero, Dialectic: Aristotle, Arithmetic: Boethius, Astronomy: Ptolemy, Grammar: either Donatus or Priscian)