I would like to bring to readers' attention a society that has been established, inspired by Pope Benedict XVI's call to artists to be 'custodians of beauty'. The Society of Catholic Artists, web site here, describes it's aims as fraternal, spiritual and intellectual. So it puts artist (and media professionals) in touch with each other; it promotes the idea that the work of the artist is founded upon his spiritual life and that artists develop intellectually so that they understand the tradition and their place within it. There is a strong emphasis on the liturgy and the events they have organised, each time in New York City, are talks and recollections organised in conjunction with Mass and, very encouragingly, the Divine Office. Two of the figures involved are very strongly interested in this connection between liturgy and culture: Fr George Rutler is based in New York and is well known as a speaker and broadcaster and is soon to be speaking in Boston Thomas More College's symposium entitled the Language of the Liturgy, Does it Matter? at the President's Council event on Saturday December 3rd at the Harvard Club (more details here). The is Fr Uwe Michael Lang who I remember from my time of attending the London Oratory, that beacon of beautiful liturgy in London. Fr Lang is a published author on the liturgy and his book Turning Towards the Lord had a preface from the then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

I would like to bring to readers' attention a society that has been established, inspired by Pope Benedict XVI's call to artists to be 'custodians of beauty'. The Society of Catholic Artists, web site here, describes it's aims as fraternal, spiritual and intellectual. So it puts artist (and media professionals) in touch with each other; it promotes the idea that the work of the artist is founded upon his spiritual life and that artists develop intellectually so that they understand the tradition and their place within it. There is a strong emphasis on the liturgy and the events they have organised, each time in New York City, are talks and recollections organised in conjunction with Mass and, very encouragingly, the Divine Office. Two of the figures involved are very strongly interested in this connection between liturgy and culture: Fr George Rutler is based in New York and is well known as a speaker and broadcaster and is soon to be speaking in Boston Thomas More College's symposium entitled the Language of the Liturgy, Does it Matter? at the President's Council event on Saturday December 3rd at the Harvard Club (more details here). The is Fr Uwe Michael Lang who I remember from my time of attending the London Oratory, that beacon of beautiful liturgy in London. Fr Lang is a published author on the liturgy and his book Turning Towards the Lord had a preface from the then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

One thing that the society has avoided is endeavouring to promote contemporary art and artists. This seems to me to be a good decision. It is a difficult balance to strike. On the one hand we want to be encouraging to those people who respond to the Pope's call and are prepared take the risk and try to be those custodians of beauty in service of the Church. But on the other, how do we decide who has been successful? Inevitably personal choice has to play a part. Choice by committee, especially if that committee contains artists, always seems to move towards mediocrity. Artist's tend not to want to openly criticise each other, because they know that it then gives others assent to be brutally frank about their own work. Also, if competitions or exhibitions are held, then in order to have sufficient paintings to show, the organisers of any such exhibition must compromise standards. This immediately undermines the idea that they are trying to encourage the highest standards and undermines the credibility of their message, which in all other respects might be very good.

Behind the idea of having exhibitions and competitions to promote artists is the assumption that the top quality artists are out there, it's just that we don't where they are. In in the naturalistic forms I do not think this is correct. There are very few artists that match up the highest standard and we already know who the best ones are. As someone who paints, my belief is that at this stage our work is one of the training and education of artists and re-establishing the principle of tradition. Perhaps the next generation of artists will emerge as capable of emulating or even surpassing the glorious work of the past by building on what some us hand on to them. Many of friends who are artists, and some of them are in my opinion the very best of those around today, happily admit that they do not compare with the greats of the past, but hope to contribute to the training and formation of the next generation in service to the Church.

So bereft are we at the moment of genuinely high quality artists, that those of genuine ability stand out in the crowd and do not need to be promoted by a non-for-profit organisation. There are already enough channels of communication to get their work out there - today more than ever. Their work speaks for itself and looking at this, my instincts tell me that market forces are the best mechanism for distribution. Those who are paying, choose what they want. It's not perfect, but I can't think of anything better.

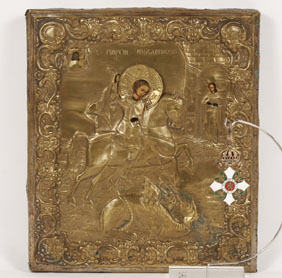

This does seem to be what happened in the field of iconography, where the reestablishment of the tradition began earlier (in the early/mid 20th century). We are now several generations of artists into this renewal of this tradition and we are seeing steadily more top quality artists who are getting commissions. On the whole, it is their work is their greatest advertisement. The lesson for all artists here is very clear in my opinion (and I acknowledge very happily that this applies to me): if patrons are not hammering at my door to commission work, then the one thing that I can try to change is the quality of my work. I must become a better artist if I want to sell more paintings.

For all this, and strange as it may seem, I am not pessimistic about the future. I do think that things are moving the right direction. We see signs of cultural renewal, in the wake of liturgical renewal (which forms arists and patrons alike). We should be realistic about where we are, but at the same time strive to encourage artists to continue to improve. It seems that the Society of Catholic Artists recognises this and aims to help them to do so.

The images are from the top: St Luke (patron saint of artists) by El Greco, in which he points to the famous icon of Our Lady and Our Lord, the 'hodegetria', that he painted; the ox is the symbol of St Luke the Evangelist and below an icon by an unknown Russian iconographer of St Luke painting his icon.

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism.

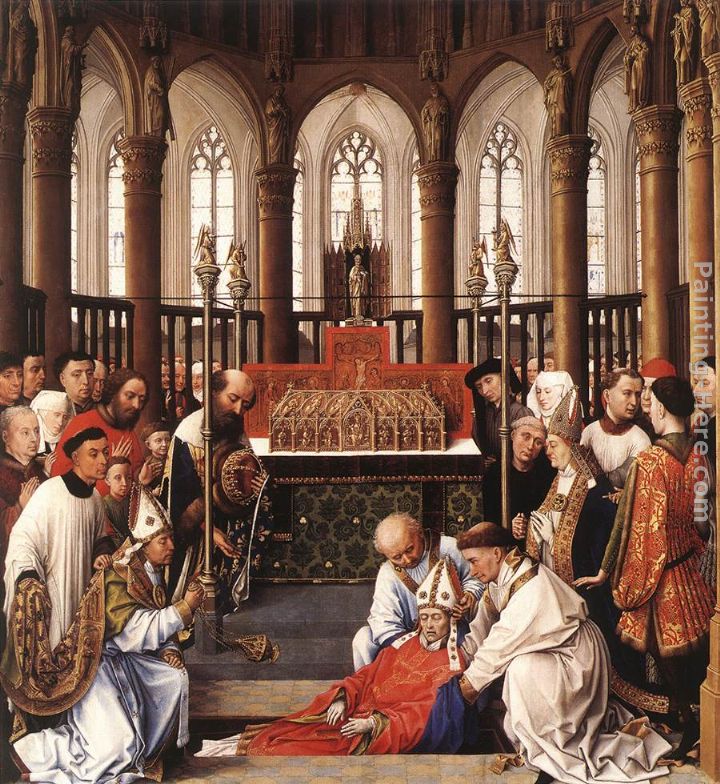

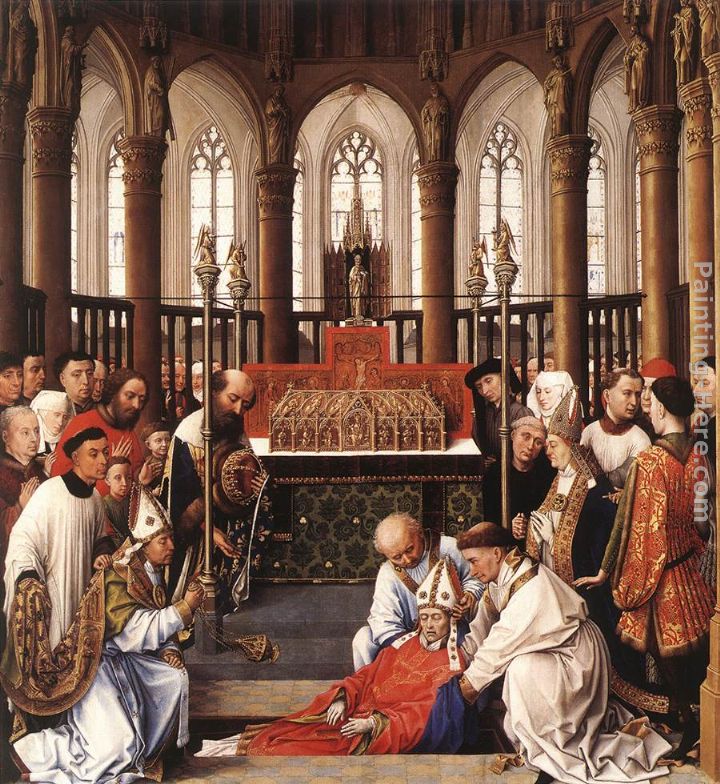

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism. Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church.

Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church. When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview.

After the Englightenment, Pope Benedict tells us in the Spirit of the Liturgy, such a dislocation occurred and this break has remained ever since. The wider culture stepped away from the culture of faith. It became one that reflected and reinforced the values, priorities and beliefs of an Enlightenment influenced worldview. There were two responses he says: one was to try to create Catholic social ghettoes that shut out mainstream culture and both were inadequate. This created an attitude of ‘historicism’ which was an unthinking and sterile attempt to recreate an idealized past. Inevitably, this approach is doomed to failure because the culture of faith is not seeking to engage and overcome the wider culture, but to escape from it. The wider culture will hammer away at the church door until it finds a weakness in the defenses and floods in. This is precisely what happened, it seems to me, after Vatican II. The intention was to open the doors and the let the Faith out to evangelise the world, but in the end the opposite happened. To blame were the improper implementation of the Council (covered may times in this site); and the other tendency described by Pope Benedict in response to the dislocation of culture: that of attempting to compromise the culture of faith with the secular culture. Secular culture is strong in reflecting the practices, beliefs and values of what is bad (eg the Enlightenment). Trying to use this to promote what is good, just results in an impotence. In the context of art, trying to portray something good with the visual vocabulary of despair either creates, in my judgement, inappropriately ugly Christian art; or else in trying to remove the ugliness, leaves the artist with a visual tool set robbed of any power at all, which produces a weak, sentimentalism – kitsch. Neither does anything to stop the erosion of the values of the Faith and the progress of the secular worldview. Inset into the text are examples of each. First a crucifixion from 1912 by Emile Nolde, which reflects the style of the mainstream art movement of the time. Second, left, we have a modern prayer card in which the artist, in my opinion, relies to heavily on sentiment. It is lacking an authentic Christian visual vocabulary that exists within, for example the baroque, and so is unable to communicate its message with vigour.

Inset into the text are examples of each. First a crucifixion from 1912 by Emile Nolde, which reflects the style of the mainstream art movement of the time. Second, left, we have a modern prayer card in which the artist, in my opinion, relies to heavily on sentiment. It is lacking an authentic Christian visual vocabulary that exists within, for example the baroque, and so is unable to communicate its message with vigour.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.