Consider two musical notes. They can be played separately, but when heard simultaneously something profound happens. Without destroying the integrity of each individual note, a new third entity has been created – a chord. What is interesting about the chord is that is created out of nothing. Crucially, the result is beautiful.

What has this got to do with business? This little example is analogous to what happens in business when wealth is created. In his encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, Pope Benedict XVI describes how wealth is created out of nothing – he uses the phrase ‘superabundance’ to describe it.

Consider two musical notes. They can be played separately, but when heard simultaneously something profound happens. Without destroying the integrity of each individual note, a new third entity has been created – a chord. What is interesting about the chord is that is created out of nothing. Crucially, the result is beautiful.

What has this got to do with business? This little example is analogous to what happens in business when wealth is created. In his encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, Pope Benedict XVI describes how wealth is created out of nothing – he uses the phrase ‘superabundance’ to describe it.

It is out of nothing because nothing materially new has been created. Through a transaction two people have exchanged one thing for another which they value more highly (otherwise they wouldn’t have chosen to do it) and wealth has been generated.

The principle of superabundance is based upon the presence of God. When human relationships are founded upon love (ie mutual self-sacrifice) then God, who is Love, is present in a special way. When He is present, they are termed ‘covenantal’ relationships. Covenantal relationships are always fruitful – something new is created out of nothing. In the family, this fruitfulness of love is realised in the creation of children. Clearly not all human relationships are intended to be as profoundly loving as a marriage, but all of them, even those in business, can be ordered to love rather than selfishness and will be more productive for it. Relationships which, in the other hand, are based upon the alignment of self-interest, are termed ‘contractual’.

Pope Benedict describes covenantal relationships in the context of business as being imbued with the principle of ‘gratuitousness’. Gratuitousness exists when something is freely bestowed by one for the benefit of another. It relates as much to the how of the action as to the what. If, for example, the way we treat someone communicates that we genuinely trust and value that person then that is going beyond the simple contractual aspects of the relationship (which are in accordance with the demands justice). This he says is not just desirable, but necessary. He goes as far as to say that, ‘Without internal forms of solidarity and mutual trust, the market cannot completely fulfill its proper economic function.’ Note he says explicitly the economic function is fulfilled – he is not referring here to incidental social benefits. There is no exchange without some wo

Beauty, I would suggest, is a litmus test of love and so of the maximisation of superabundance. When it is present in our actions then it indicates that we are opening ourselves up to the source of inspiration for greatest creativity and productivity. The generation of ideas and seeing them through to fruition is the basis of entrepreneurial activity.

Beauty, I would suggest, is a litmus test of love and so of the maximisation of superabundance. When it is present in our actions then it indicates that we are opening ourselves up to the source of inspiration for greatest creativity and productivity. The generation of ideas and seeing them through to fruition is the basis of entrepreneurial activity.

To the extent that what we do is beautiful, it will be in harmony with the common good also. This means that in serving the aims of the business, there can be no conflict with society or God’s creation. If this is true then we might have found the route to genuinely ‘green’ business activity: one in which the more profitable and productive it is, the better it will be for the environment. This is something much more profoundly ‘green’ that many green activists envisage. The assumption behind the secular worldview appears to be that man is necessarily in conflict with the environment and so their solution is damage limitation in one form or another. This usually boils down to reducing the amount of human activity (which in turn usually equates to reducing the number of human beings on the planet). In contrast, the idea of superabundance offers the vision of a transformed human activity that improves upon the natural world. It is better than an activity that is neutral ie does not destroy the wilderness; it actually improves and perfects it. Nature is meant to flourish under man’s influence, and with God’s grace it is possible. When what we do is in harmony with nature, then in contrast to what we described before, the more active man, is the better it is for nature; and accordingly the more people there are doing it, the better.

How can we combine consideration of what is beautiful with the other considerations of running a business? Profit has to be the driving consideration and this doesn’t change that. Provided that moral law is not contravened the motive of profit will dictate what decisions are made. But an education in beauty (as described in more detail here) will naturally stimulate ideas that are simultaneously good for business (in the sense of profitable) and in harmony with the common good.

There are occasions when I can imagine the principle of beauty being considered consciously: for example when there are number of options available that seem equally valid by other criteria. At that point one might ask which is the most beautiful option? Even then I don’t imagine it will always be an easy criterion to use, we may be trying to apply it in situations in which beauty is not normally associated. In some situations it will be obvious though: if price is set by the perception of the value of an object, and if we make objects for sale more attractive then people will pay more. This is the idea that pitches the more expensive yet visually appealing and user-friendly Apple against the cheaper PC. But we are talking of something deeper as well. Beauty is a guide (along with morality) to the right exercise of our free will. Whereas morality restricts options, beauty multiplies them.

There is another aspect to this. The more we take the principle of beauty into account, the more our actions will be covenantal. We will giving of ourselves and going beyond the limited demands of justice. This gift of self, says the Pope, ‘by its nature goes beyond merit, its rule is that of superabundance.’ Business has its place in the fulfilment of the common good and to that end must be seen as something that is good in itself and business done beautifully is going to be closer to the fulfilment of that ideal.

It is important to note that we are living in a fallen world, and so seeking to institute a covenantal model of operation does not preclude contracts. The market is regulated by law in accordance with the principles of justice (or at least it ought to be), and contracts reflect this. While contracts are necessary, they are never enough. Contracts alone cannot generate the trust and goodwill that oil the wheels of commerce. It is the covenantal behaviour that permeates this legalistic structure that does this and so must be there too. I know of one person who has successfully developed and applied a systematic method of identifying and developing naturally occurring covenantal relationships. John Carlson of System Change, Inc. looks for those revenue generating covenantal relationships in the companies that he works with. They permeate through and sit alongside the formal management structures in any company (and extend out into the client base). Once identified, he uses these as a basis for sustainable growth in accordance with a covenantal business model.

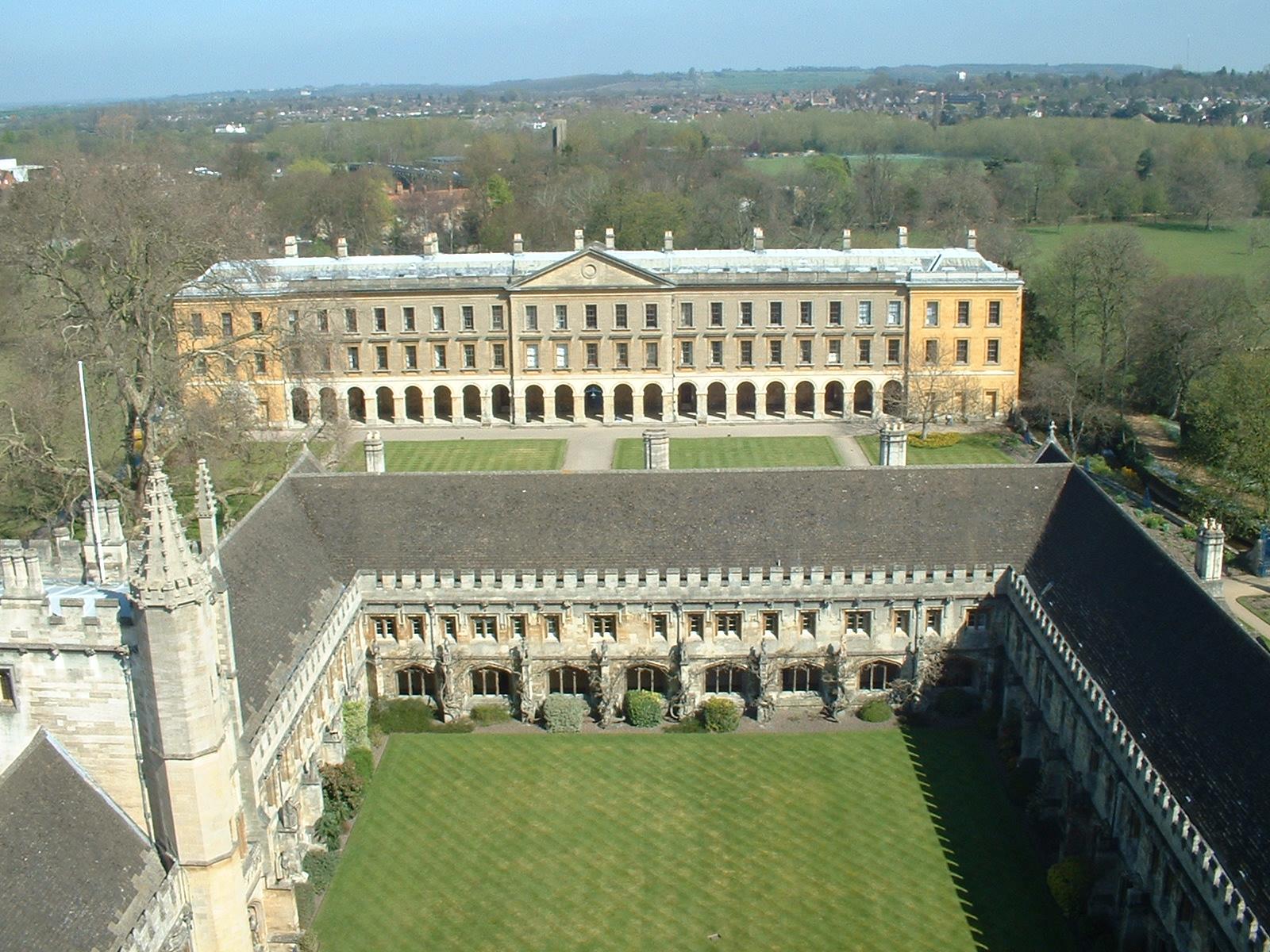

These considerations, I believe will hasten the business on to its proper end. The end of a good business is the steady creation of wealth in harmony with the common good; but take note, the right end of a bad business (if it doesn’t change) is failure! The indications are that the employment of these principles in the past (for example by the Benedictines) and by modern entrepreneurs works well for sustainable growth when understood in these terms.

For more detail on these principles see articles Sustainable Growth and Art, Grace, Education and the Beautiful Business, both at our sister site, www.thewayofbeauty.info.

PS There are two more blogs that have recently started that discuss these and similar matters: Andreas Widmar has started a blog Faith and Prosperity Nexus which is about 'sound business and strong faith in action' and knowing Andreas as I do, it'll be about enjoying the process too!

Fr Michael Sweeney's new blog, Re-Visioning Society discusses the common good and Catholic social teaching. He is an insightful and inspiring speaker if you ever get a chance to hear him.

http://thewayofbeauty.org/2012/04/the-green-green-grass-of-texas/

A Christmas tree farmer working for the common good The Fall is a beautiful season in New England, as every tourist brochure will tell you, and so I am out and about a lot at the moment. I was delighted on a recent walk near Henniker in New Hampshire to come across Forster's Christmas Tree Farm. The farm is situated on a hilltop and his shop has a deck where you can sit and enjoy a beautiful panoramic view of the surrounding area. Steve Forster the charming proprietor was in and so I immediately starting quizzing him about local walks on developed farmland. Regular readers will know why (otherwise the curious can go here , here and here for past articles outlining my thoughts on the subject). Steve immediately told me that he has opened up trails on his land and makes them available to local people. It's not the conventional farming landscape of cereal crops or pastureland, but nevertheless, here is the land being put to productive use and an landowner who is happy to make it available as a resource for those who will use the privilege responsibly.

A Christmas tree farmer working for the common good The Fall is a beautiful season in New England, as every tourist brochure will tell you, and so I am out and about a lot at the moment. I was delighted on a recent walk near Henniker in New Hampshire to come across Forster's Christmas Tree Farm. The farm is situated on a hilltop and his shop has a deck where you can sit and enjoy a beautiful panoramic view of the surrounding area. Steve Forster the charming proprietor was in and so I immediately starting quizzing him about local walks on developed farmland. Regular readers will know why (otherwise the curious can go here , here and here for past articles outlining my thoughts on the subject). Steve immediately told me that he has opened up trails on his land and makes them available to local people. It's not the conventional farming landscape of cereal crops or pastureland, but nevertheless, here is the land being put to productive use and an landowner who is happy to make it available as a resource for those who will use the privilege responsibly.