Thomas More College Adds Academic Drawing to its Way of Beauty Program I am delighted to announce new developments in the Way of Beauty program for undergraduates at The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts’ in New Hampshire. It is partnering with the internationally renowned Ingbretson Studio to expand the Way of Beauty Program to include a series of weekly classes in the academic method of naturalistic drawing, which has its roots in the baroque and the High Renaissance, including the known methods of Leonardo da Vinci. This is a significant addition to its college courses and summer programs in sacred art.

Thomas More College Adds Academic Drawing to its Way of Beauty Program I am delighted to announce new developments in the Way of Beauty program for undergraduates at The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts’ in New Hampshire. It is partnering with the internationally renowned Ingbretson Studio to expand the Way of Beauty Program to include a series of weekly classes in the academic method of naturalistic drawing, which has its roots in the baroque and the High Renaissance, including the known methods of Leonardo da Vinci. This is a significant addition to its college courses and summer programs in sacred art.

This new initiative directly challenges modern art theories and seeks to renew in aspiring artists an appreciation for Catholic principles in sacred and secular art.

Students participating in the program will spend one day each week at Ingbretson Studio in Manchester, NH—a fifteen minute drive from Thomas More College’s campus. In addition to the practical method, they will study the philosophy behind academic drawing and painting.

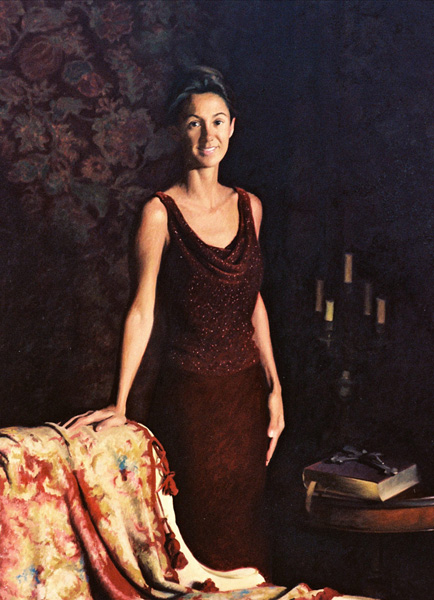

Paul Ingbretson is himself a modern master of the Boston School Tradition, which seeks to combine the truth of impressionist color with good draughtsmanship, sound composition, and skillful paint handling. His studio is known internationally and has trained some of the best known artists painting today, including Catholic portrait painter Henry Wingate, who teaches at the Way of Beauty Atelier summer program.

Ingbretson was taught in Boston in the 1970s by R. Ives Gammell, who is the teacher, writer, and painter who almost single-handedly kept alive the traditional atelier method of painting instruction.

Through Gammel, Ingbretson can trace a line through the Boston School, to the Parisateliers of the 19th century, and to the 17th century baroque. His students tread a path taken by such masters as the great American artist John Singer Sargent and the Spanish 17th Master, Velazquez.

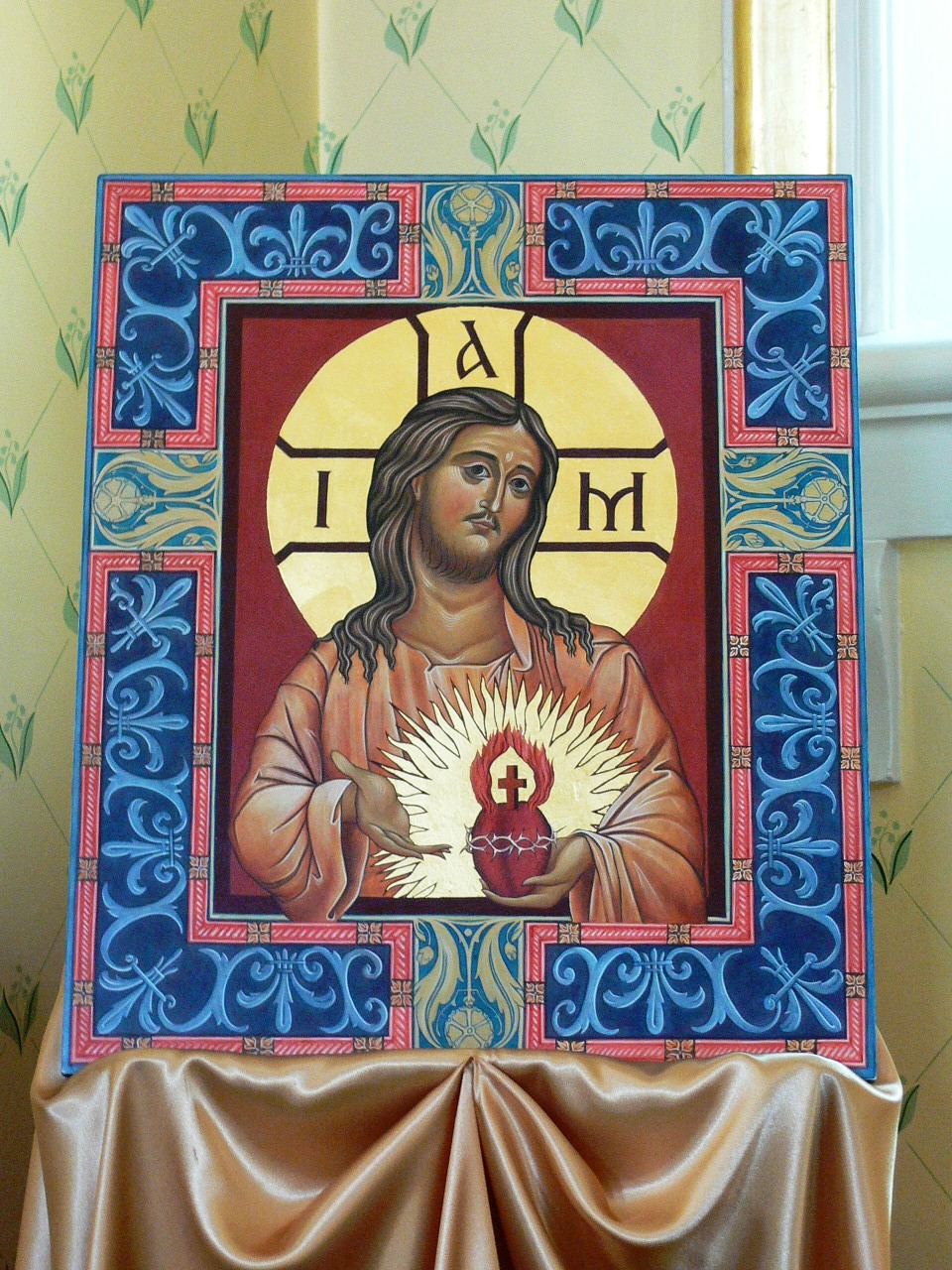

This partnership with Ingbretson Studio helps the College achieve one of the primary objectives of the Way of Beauty Program—to form a new generation of professional artists that produce art that lifts the soul to God.

This partnership with Ingbretson Studio helps the College achieve one of the primary objectives of the Way of Beauty Program—to form a new generation of professional artists that produce art that lifts the soul to God.

It is imperative that aspiring Catholic artists obtain, as well as the skills, a firm understanding of the Western tradition, which Thomas More College provides through its curriculum. It is further imperative that aspiring Catholic artists receive firm spiritual formation from which they can derive inspiration, which again, is available at the college.

During their four years at TMC students will attend a series of courses in Catholic art and architecture; experience art first-hand during our semester in Rome; produce an icon of their own through our St. Luke Sacred Art Guild, assist me in producing sacred art for our chapel; and further hone their skills through opportunities like the one now available through Ingbretson Studios.

The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts provides a four-year undergraduate education which develops young people intellectually, ethically, and spiritually in the Catholic tradition and in faithfulness to the Magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church. Thomas More College introduces its students to the central questions of Western Civilization—and to the Church’s response. It teaches students how to reason, engage in academic discourse, and to write. Students from Thomas More College are shaped into becoming faithful leaders who will be able to pursue the individual vocations which God has given each of them.

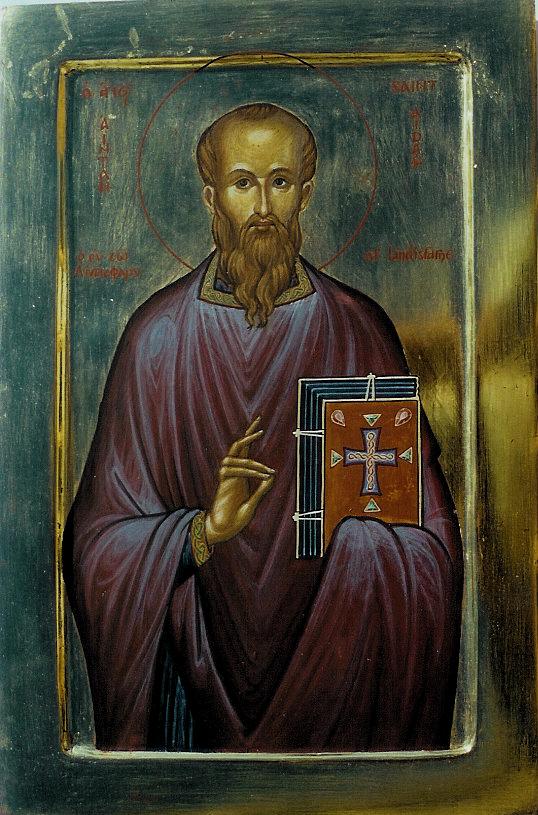

All the artwork shown is the product an academic training. The charcoal drawing above is my own work; the painting of the two children is by John Singer Sargent; the portrait below is by Henry Wingate. The paintings below that are by the 19th century master of the Boston school, Joseph DeCamp