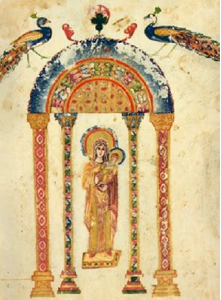

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

I think that the answer is that some symbols are worth persevering with, and some should be abandoned. First, it is part of our nature to ‘read’ invisible truths through what is visible. This does not only apply to painting. The whole of Creation is made by God as an outward ‘sign’ that points to something beyond itself to Him, the Creator. Blessed John Henry Newman put it in his sermon Nature and Supernature as follows: "The visible world is the instrument, yet the veil, of the world invisible – the veil, yet still partially the symbol and index; so that all that exists or happens visibly, conceals and yet suggests, and above all subserves, a system of persons, facts, and events beyond itself.” It is important to both to make use of this faculty that exists in us for just this purpose; and to develop it, increasing our instincts for reading the book of nature and in turn, our faith.

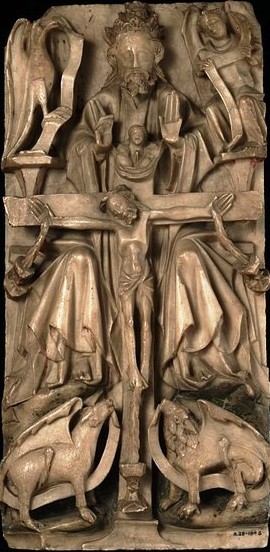

However, coming back to the context of art again, some discernment should be used, I suggest. I would not be in favour of creating an arbitrarily self-consistent symbolism. The symbol must be rooted in truth. The symbolism in the iconographic tradition is very good at following this principle. This is best illustrated by considering the example of the halo. This is very well known as the symbol of sanctity in sacred art. There are very good reasons for this. The golden disc is a stylized representation of a glow of uncreated, divine light, shining out of the person. Even if this were not already a widely known symbol, it would be worth educating people about the meaning of it, because in doing so something more is revealed. When however, the representation of a halo develops into a disc floating above the head of the saint, as in Cosme Tura’s St Jerome, or even a hoop, as in Annibale Caracci’s Dead Christ Mourned, (both shown) then it seems to me that the symbol has become detached from its root. Neither could be seen as a representation of uncreated light. These latter two forms, therefore, should be discouraged.

Similarly, those symbols that are rooted in the gospels or in the actual lives of the saints should be encouraged and the effort should be made, I think, to preserve or, if necessary, reestablish them. The tongs and coal of the prophet Isaias relate to the biblical accounts of his life. The inclusion of these, will generate a healthy curiosity in those who don’t know it, and so might direct them to investigate scripture. The picture shown below, incidentally, is one that I did as a demonstration piece for our recent summer school at Thomas More College in New Hampshire.

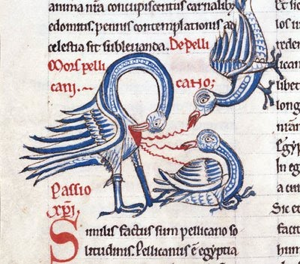

In contrast consider the peacock and the pelican. The peacock, as already mentioned, does not, we now know, have incorruptible flesh. The pelican is a symbol of the Eucharist based upon the erroneous belief in former times that pelicans feed their young with their own flesh. The immediate reaction is that these should not be used (I am not aware of any biblical reference to these two creatures that would justify it). However, I am torn by the fact that both of these are beautiful and striking images, even if based in myth.

Also, it might be argued, and this is particularly true for the pelican, that to use it is not resurrecting an obscure medieval symbol. It is an ancient symbol certainly - and St Thomas Aquinas's hymn to the Eucharist, Adore te devote called Christ the 'pelican of mercy'. But it lasted well beyond that. It was very widely understood even 50 years ago. Awareness of it is still common nowadays amongst those who are interested in liturgy and sacred art. Perhaps an argument could be made that even when the reason for the use of symbol is based in myth, if that is known and understood, and when that symbol recognition is still widespread enough to be considered part of the tradition, it should be retained. We should also remember that modern science is not infallible, and we moderns could be those who are mistaken about the pelican! My Googling research (admittedly even less reliable than modern science) revealed that the coat of arms of Cardinal George Pell has the image of the pelican. If this is so, I imagine he would have something to say about the issue also!

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

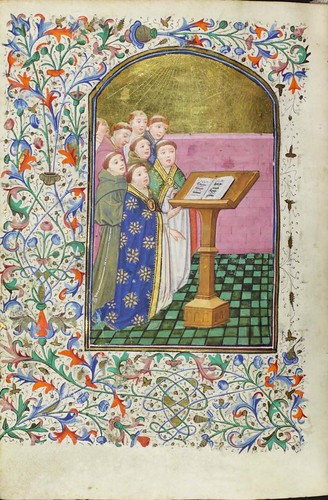

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,  If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation. Chant:

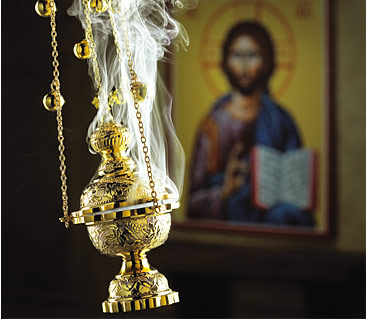

Chant: Incorporating the sense of smell

Incorporating the sense of smell

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 ( If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy. Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us? Mark the Hours

Mark the Hours So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication  The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,  If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one  And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one,

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one,

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow)

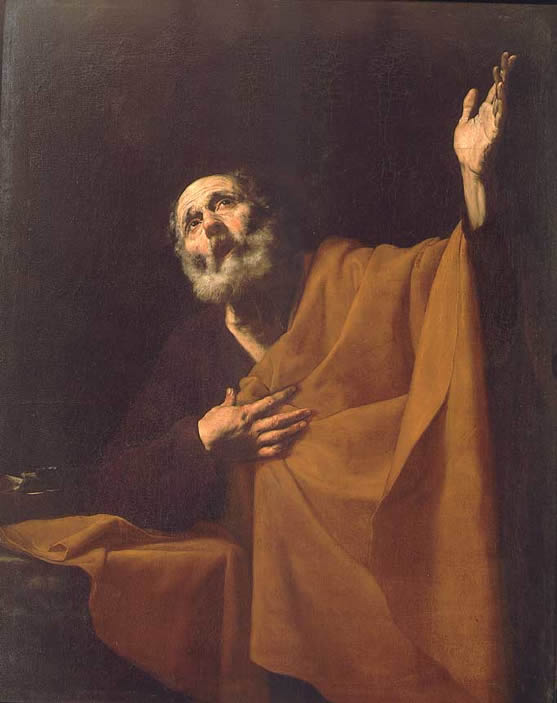

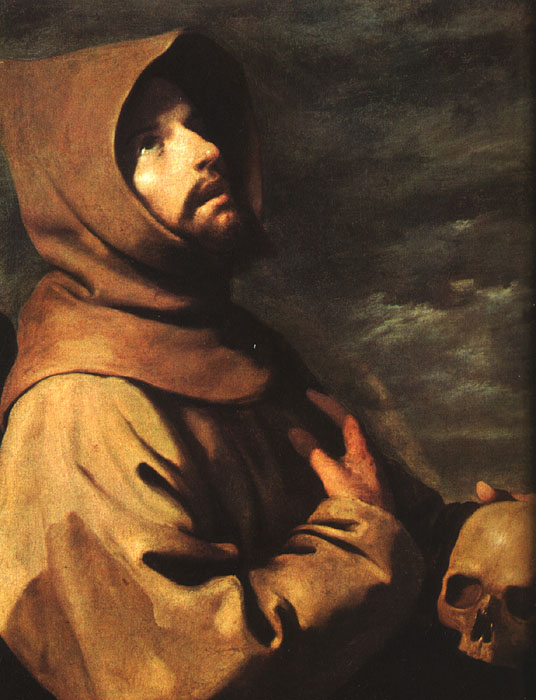

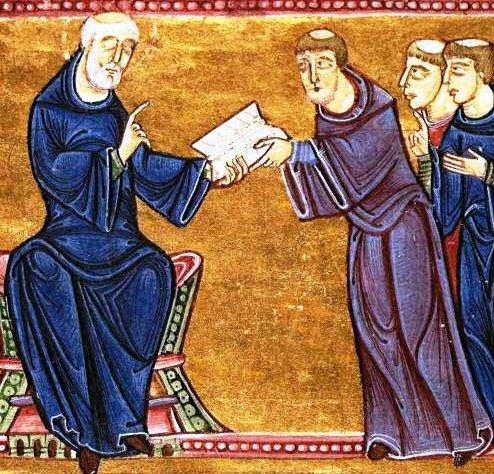

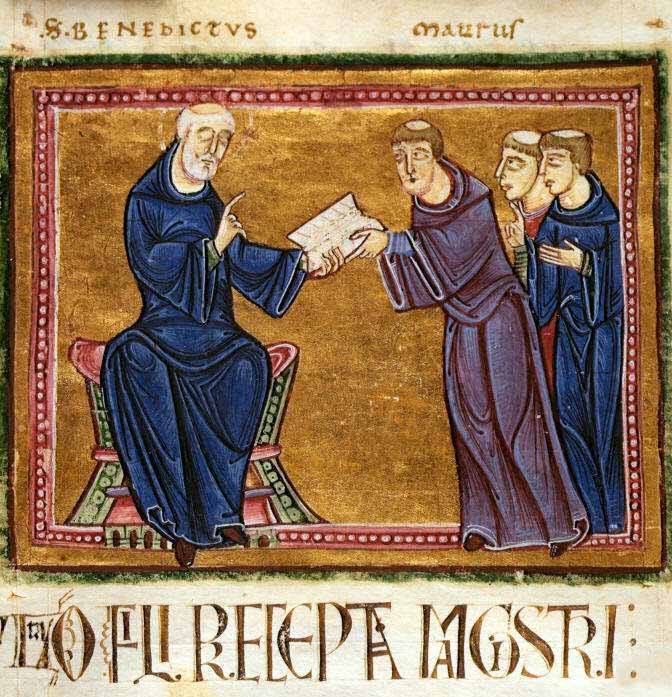

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow) Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year: