A culture that promotes diversity celebrates differences, and ultimately leads to conflict and death; the antidote is Catholic culture which is universal. It celebrates the uniqueness of every person and what is common to each of us, so binding us in love.

Every society's culture is a reflection of its core beliefs and values. At the heart of this therefore is man's attitude to God and the most powerful factor in influencing this is worship.

This principle was articulated by the Church Fathers with the phrase lex orandi, lex credendi - rule of prayer, rule of faith. What this phrase of the Fathers is saying, as I understand it, is that man is made to worship God and how he does it affects everything else he believes and, in turn, what he does. If we wish to achieve cultural reform, therefore it seems, we should look first at our participation in the liturgy and strive for the ideal that the Church asks of us.

To the degree that man does not worship in the manner proscribed by the Church, then he will worship in another, lesser way; or else very likely he will worship something else. At this point his worship has deviated from some objective norm and now reflects, as much as forms, the beliefs of the person. Even those who think of themselves of having no religion will submit to principles and ideals that at the deepest level are just assumed, accepted on faith so to speak; and this instinct for worship will manifests itself somehow with customs and practices developing in accordance with them. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI discusses this in his book, so often referred to in this blog, the Spirit of the Liturgy. To the degree that this instinct for worship is repressed or misdirected, then man is trying to negate something fundamental to him and the result is despair and a culture of disharmony and ugliness; and ultimately a culture of death.

If one had to name one idea that characterizes the formation of modern culture I think one of the first that would come to mind would be ‘diversity’. It is a word that, as it is often used, seems to encapsulate the relativism of the modern day. It is consistent with the personal philosophy of ‘I’ll let you do whatever you want to do...as long as it doesn’t interfere with me doing whatever I want to do’. In my experience, diversity is accepted as a good almost without question by many people. And true to this instinct of worship, those who swear by it talk of ‘celebrating' it.

What is celebrated (for example at art fairs in which showcase artists from many of the world’s traditional cultures), we are told, is the variety of different cultures across the globe. I used to enjoy attending these events until at some point it struck me that they are as much an exercise in appeasing the consciences of those who attend as they are about promoting craftsmanship or art. Judging from conversations, attendees were mostly secular Westerners and it struck me that their interest in these other cultures was only superficial. By this outward sign of tolerance and broadmindedness towards others, they got a warm fuzzy feeling inside and hoped to justify to themselves their refusal to submit to authority in their personal lives. Certainly this is what motivated me when I was a secular Westerner before my conversion to Catholicism. The more I exercised tolerance and ‘non-judgmentalism’ in regard to others, the more I felt justified in rejecting any external authority in regard to my own conduct. I had earned the right of tolerance and non-judgmentalism from others and so could now do just what I wanted. What I didn’t realize until later was that in the end it wasn’t the opinions of others that I needed to worry about, it was my own conscience and that was something I couldn’t escape. Deep down part of me knew that I was doing wrong. As I once heard someone say, low self-esteem is a modern psychological phrase for what used to be call ed a guilty conscience. It was this acknowledgement of the truth deep inside me, which took hold gradually, that moved me first to guilt, despair and then to God.

It may be that I am being overly cynical here and judging people people by my own standards - i am sure that it part some people genuinely want to see the end of conflict by promoting tolerance between different societies and see this as a way of doing it. However, it is interesting that for all the talk of tolerance and diversity, this does not seem to extend, in my experience, to an unhesitating inclusion of Chritianity and especially the Church. The standard accusation levelled at the Church are the great secular sins of intolerance and ‘ judgmentalism’ (especially against women and homosexuals).

In fact, given their position, their desire to attack the Church is rational. It does stand up firmly against what they espouse, but not for the usual reasons the give. It does claim authority in moral matters and so will shine an unwanted spotlight on the consciences of those who act against them. The truth of what the Church stands for is evidenced by the fact that it's teaching makes people so uncomfortable. People are seeking to blame the Church for what their own consciences tell them. And the Church does believe in justice and judgment. However, the judge is just judge, God; and this exrcise of justice is tempered of course, as its critics often neglect to point out, with love and mercy.

And in regard to culture, which is what we are considering here, it stands out squarely against the principle of diversity by asserting a principle of universality.

To my mind, the flaw in the idea of diversity is that it focuses on differences. Rather than bringing us together (which is the stated intention), this separates us from each other and leads to conflict. We see this in Britain where there are immigrant communities which so strongly preserve the culture of their original country that there are ghettos in which the assimilation into British culture has barely taken place. Successive generations do not appear to be integrating with British culture. Rather they are more separate from it and less inclined to assimilate than the generation of their parents who came here. In extreme cases and very sadly, some feel so alienated from the culture of Britain and so hostile to it that they have tried to bomb their host country out of existence.

The antidote to this is love, which recognizes the uniqueness of every person, and without compromising personal freedom binds us together in harmony. Accordingly, in the context of cultures what is important is not what differentiates us but what binds us together. These are the elements that are common to all of us. Or put another way, what is 'universal'.

As we know, the word 'catholic' means 'universal'. Just as Church teaching is appropriate for every person; so is Catholic culture. This will not suppress individuality, but encourage it to flourish properly in harmony with all others. A Catholic culture is the only culture that is truly universal. Others are in some way a reflection of a lesser account of the truth. Catholic culture, because it is universal, cuts out no one and appeals to everyone at a personal level. It accomodates the uniqueness of each person, but binds us together with what is common.

The problems of modern socitey are cultural. The antidote, to the culture of death (whether we think of abortion, contraception or exploding bombs) therefore is not political, but cultural. How do we change it. The long term answer to the the culture of death is a culture of life. I have discussed this more in an article 'Universality, Noble Accessibility and Pop Culture that Will Save the World'.

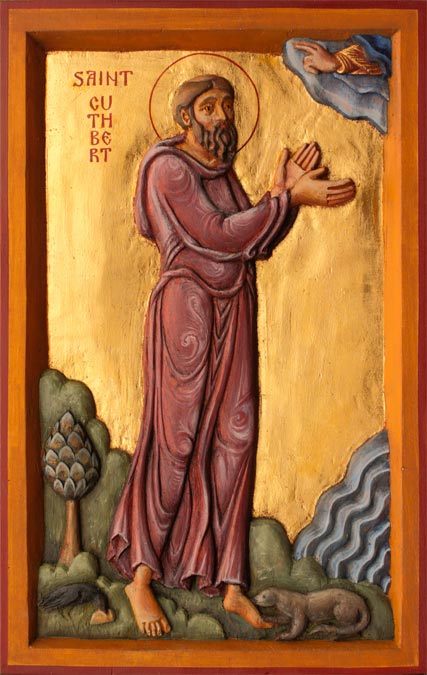

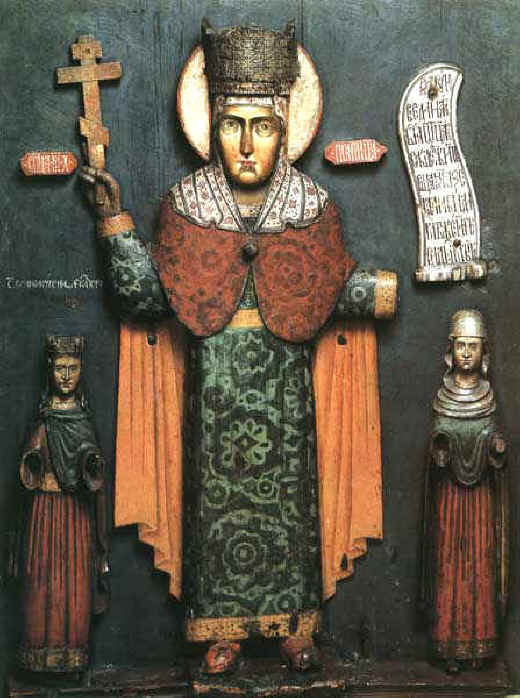

Universality is not the same as uniformity. A culture of uniformity obliterates the personal and demands a sterile conformity. In the universality of the Catholic culture, the general is always expressed through the particular but when it is an expression of what is universal in us, we can always recognize it and are attracted to it, even when it is not our own culture. This is its evangelising power. It is expressed perfectly in the traditions of Gregorian chant and the artistic traditions of the Church, for example iconographic sacred art (as the oldest and best established form of liturgical art of the Church). Although there is great diversity within each tradition, much of it particular to times and places, the universal principles that define it are never compromised. If the culture of faith is rooted in these living liturgical forms of art and music then it will feed the wider culture in the same way and affect the way we live our ordinary lives. Then we will have something that speaks to others.

The way to avoid ghettos of the sort we see in the cities of Europe is to offer a Catholic culture, in the widest sense of the word, that attracts all. Without a culture of the Faith to offer to people, the alternative to diversity is uniformity, which is even less attractive. For uniformity stifles the spirit even more powerfully. When these immigrants looked at British culture, they were given the choice and they chose not to assimilate. They were not rejecting a Catholic culture, but a secular culture which was uniform, and ugly. In many respects it was less than what they already had. This is why every modern city, despite giving architects virtually a free range in choosing what they want to design, looks the same as every other. It is their very attempts to be different for what they manifest in following this impulse is disorder- there is no order outside God’s order, only disorder.

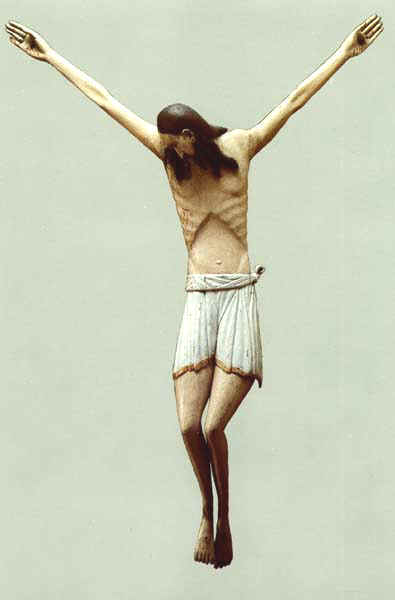

So what's the answer? I believe that in the long term it is cultural and not political. How do we achieve this. It starts at home. We must look to ourselves. The domestic church is the seat of culture. We focus on a piety that has the liturgy at its centre, and at home this means the liturgy of the hours. But at a personal level, which is the one over which I have most control, I can strive for a personal transformation by which in some small way I can participate in the transfigured light of Christ. Because each person is in relation with those around them, even the most cloistered monk, they will effect change not through PR campaigns, but through the transforming influence of our personal relationships. We should not underestimate the power of this - we are told we are told that no one is more than six handshakes away from any other member of society. I have written at great length about the principles at work here. (In the article linked, I had in mind economic and cultural change, but the principle is exactly the same)

Lex orandi, lex credendi...I'm off to pray the Divine Office!

Recently a reader contacted me with a question about Fra Angelico's fresco of the Last Supper. Is there a particular reason why some of the figures are kneeling and others not? And who is the female figure present? In answer to the first, I assumed that he was emphasising that the Last Supper is the Mass I don't know if there is any tradition that governs who knelt and who sat. (I find it interesting that Judas, with the black halo is kneeling in line.) I guessed that the lady present is Our Lady (or perhaps Mary Magdalene) but didn't really know. Ordinarily the names would be present (in accordance with the theology of Theodore the Studite from the 9th century). So this is an additional question: does anybody know who she is and also, do you know if Fra Angelico put the names of those portrayed somewhere as part of this painting? If not I would be interested to know why not as names are necessary to make an image worthy of veneration.

I posed these questions on the New Liturgical Movement blog also, so I am curious to see how the answers of the two readerships varies!

Recently a reader contacted me with a question about Fra Angelico's fresco of the Last Supper. Is there a particular reason why some of the figures are kneeling and others not? And who is the female figure present? In answer to the first, I assumed that he was emphasising that the Last Supper is the Mass I don't know if there is any tradition that governs who knelt and who sat. (I find it interesting that Judas, with the black halo is kneeling in line.) I guessed that the lady present is Our Lady (or perhaps Mary Magdalene) but didn't really know. Ordinarily the names would be present (in accordance with the theology of Theodore the Studite from the 9th century). So this is an additional question: does anybody know who she is and also, do you know if Fra Angelico put the names of those portrayed somewhere as part of this painting? If not I would be interested to know why not as names are necessary to make an image worthy of veneration.

I posed these questions on the New Liturgical Movement blog also, so I am curious to see how the answers of the two readerships varies!