Going Local for Global Change.

How About a Chant Cafe with Real Coffee ..and Real Chant?

Going Local for Global Change.

How About a Chant Cafe with Real Coffee ..and Real Chant?

There is a British comedienne who in her routine adopted an onstage persona of a lady who couldn't get a boyfriend and was very bitter about it (although in fact as she became a TV personality beyond the comedy routines, she revealed herself as a naturally engaging and warm character who was in fact happily married with a child). Jo Brand is her name and she used to tell a joke in which she said: 'I'm told that a way to a man's heart is through his stomach. I know that's nonsense - guys will take all the food you give them but it doesn't make them love you. In fact I'll tell you the only certain way to man's heart...through the rib cage with a bread knife.' Well wry humour aside, I think that in fact there is more truth to the old adage than Jo Brand would have acknowledged (on stage at least). Perhaps we can touch people's hearts in the best way through food and drink, and in particular coffee.

There is a coffee shop in Nashua NH where I live called Bonhoeffer's. It is the perfect place for conversation. They have designed it so that people like to sit and hang out - pleasing decor, free wifi, and different sitting arrangements, from pairs of cozy arm chairs to highbacked chairs around tables. The staff are personable and it is roomy enough that they can place clusters of chairs and sofas that are far enough apart so that you don't feel that you are eavesdropping on your neighbors' conversation; and close enough together that you feel part of a general buzz of conversation around you. There is not an extensive food menu but what they have is good and goes nicely with the image it conveys of coffee and relaxed conversation - pastries, a slice of quiche or crepes for example. It has successfully made itself a meeting place in the town because of this.

This is all very well and good, if not particularly remarkable. But, you wouldn't know unless you recognized the face of the German protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer in the cafe logo and started to ask questions, or noticed and took the time to read the display close the door as you are on your way out, that it is run by the protestant church next door, Grace Fellowship Church. Furthermore a proportion of turnover goes towards supporting locally based charities around the world - they list as examples projects in the Ukraine, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Haiti and Jamaica on their website. Talks and events linked to their faith are organised and there are pleasant well equipped meeting rooms available for hire. I include the logo and website to illustrate my points, but also in the hope that if Bonhoeffer's see this they might push an occasional free coffee in my direction...come on guys!

Well, it was worth a try. Anyway, back to more serious things...the presentation of their mission does not even dominate the cafe website which talks more about things such as the beans they use in their coffee, prices and opening times and the food menu. The most eye-catching aspect when I was nosing around is the announcement of the new crepes menu! There is one tab that has the heading Hope and Life Kids and when you click it it takes you through to a dedicated website of that name, here , which talks about the charity work that is done.

I went into Bonhoeffer's recently with Dr William Fahey, the President of Thomas More College, just for cup of coffee and a chat, of course, and he remarked to me as we sat down that this is the sort of the thing that protestants seem to be able to organize; and how we wished he saw more Catholics doing the same thing.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

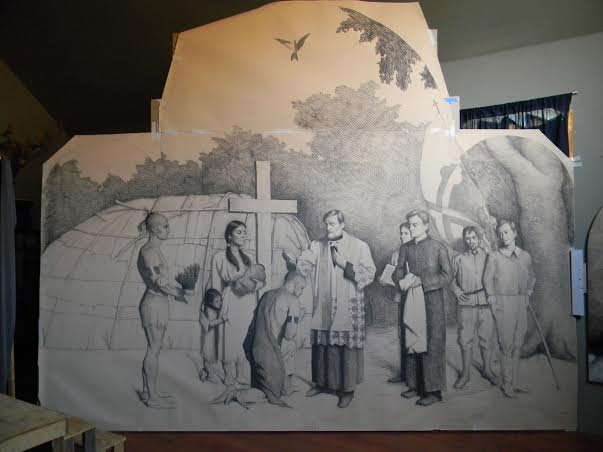

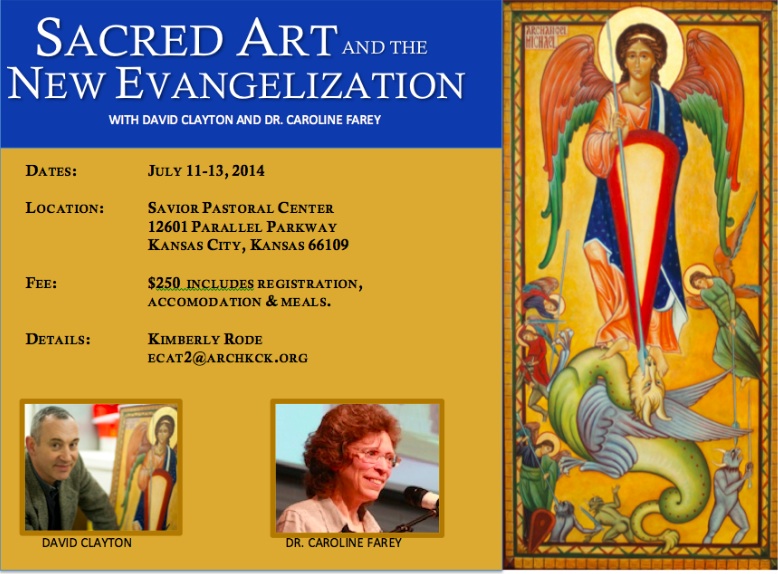

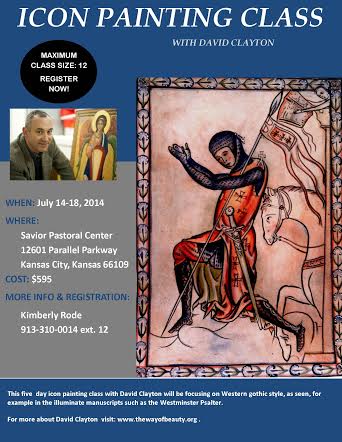

I don't know how to run coffee shops, so I would be happy with a first step that copied precisely theirs - the establishment of coffee shop that competes with all others in doing what coffee shops are meant to do, sell coffee. Then I would offer through this interface talks and classes that transmit the Way of Beauty, many of which are likely to have an appeal to many more than Catholics (especially those with a 'new-age spiritual' bent). There are a number that come to mind that attract non-Christians and can be presented without compromising on truth - icon painting classes; or 'Cosmic Beauty' a course in traditional proportion in harmony based upon the observation of the cosmos; or praying with the cosmos - a chant class that teaches people to chant the psalms and explains how the traditional pattern of prayer conforms to cosmic beauty.

A yoga class that has the word yoga but is simply a adoption of the physical aspects would attract people who are open to spirituality. Yoga is very successful in turning people with no previous inclination to the spiritual to Eastern spirituality - so why not offer Christian mediation/contemplative prayer and incorporate this into the instruction. I once had discussions with a Dominican about the known prayer postures of St Dominic. He showed me some stick figure diagrams he had drawn to represent them. He thought that these could be the basis for a Christian yoga that engages people spiritually through a focus on the physical. I don't know if he was right, but something on these lines would be good.

Another way of engaging people who are then going to be open to mediation, chant and retreats is to have 12-step fellowship groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous meeting closeby. I am aware of several priests who go to AA and also many converts to Catholicism who were first given a faith in God through such groups. The 12 steps are a systematic application of Christian principles (without reference to the Church). The non-demoninational character of the groups does mean that people can be misdirected towards other faiths in their search, but if we were present to provide an attractive picture of the Faith, it would attract interest I am sure.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern 'universalist' approach to religion in which they saw each great 'spiritual tradition' as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously - this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity - although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern 'universalist' approach to religion in which they saw each great 'spiritual tradition' as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously - this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity - although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly 'TLO meetings' would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly 'TLO meetings' would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

We could perhaps sell art by making it visible on the walls or have a permanent, small gallery space adjacent to the sitting area (provided it was good enough of course - better nothing at all than mediocre art!). All would available in print form online as well of course, just as talks could be made available much more widely and broadcasted out across the net if there was interest. This is how the local becomes global.

What I am doing here is taking the business model of the cafe and combining it with the business model of the Institute of Catholic Culture which is based in Arlington Diocese in Virginia. I wrote about the great work of Deacon Sabatino and his team at the ICC in Virginia in an article here called An Organisational Model for the New Evangelization - How To Make it At Once Personal and Local, and have International Recognition. His work is focussed on Catholic audiences, and is aimed predominently at forming the evangelists, rather than reaching those who have not faith (although I imagine some will come along to their talks). By having an excellent program and by taking care to ensure that his volunteers feel involved and are appreciated and part of a community (even organising special picnics for them) Deacon Sabatino has managed to get hundreds volunteering regularly.

Another group that does this just well is the Fra Angelico Institute for Sacred Arts in Rhode Island run by Deacon Paul Iacono. I have written about his great work here. The addition of a coffee shop give it a permanent base and interface with non-Catholics and even the non-churched.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past 'post-Christian' that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your 'higher self' and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don't know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn't arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past 'post-Christian' that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your 'higher self' and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don't know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn't arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

Here's the additional element that holds it all together. As well as the workshops or classes I have mentioned I would have the Liturgy of the Hours prayed in a small but beautiful chapel adjacent to and accessible from the cafe on a regular basis, ideally with the full Office sung. The idea is for people in the cafe to be aware that this is happening, but not to feel bound to go or guilty for not doing so. I thought perhaps a bell and announcement: 'Lauds will be chanted beginning in five minutes in the chapel for any who are interested.' Those who wish to could go to the chapel and pray, either listening or chanting with them. The prayer would not be audible in the cafe. So those who were not interested might pause momentarily and then resume their conversations.

From the people who attend the TLO meetings I would recruit a team of volunteers might volunteer to sing in one or more extra Offices during the week if they could. If you have two people together, meeting in the name of Jesus, they can sing an Office for all. The aim is to have the Office sung on the premises give good and worthy praise to God for the benefit of the customers, the neighbourhood, society and the families and groups that each participates in aside from this and for the Church.

When the point is reached that the Office is oversubscribed, we might encourage groups to pray on behalf of others also in different locations by, for example singing Vespers regularly in local hospitals or nursing homes. I describe the practice of doing this in an appendix in The Little Oratory and in a blog post here: Send Out the L-Team, Making a Sacrifice of Praise for American Veterans.

As this grows, the temptation would be to create a larger and larger organization. This would be a great error I think. The preservation of a local community as a driving force is crucial to giving this its appeal as people walk through the door. There is a limit to how big you can get and still feel like a community. Like Oxford colleges, when it gets to big, you don't grow into a giant single institution, but limit the growth and found a new college. So each neighborhood could have its own chant cafe independently run. There might be, perhaps a central organization that offers franchises in The Way of Beauty Cafes so that the materials and knowledge needed to make it a success in your neighborhood are available to others if they want it.

I have made the point before that eating and drinking are quasi-liturgical activities by which we echo the consuming of Christ Himself in the Eucharist (it is not the other way around - the Eucharist comes first in the hierarchy). So it should be no surprise to us that food and drink offered with loving care and attention open up the possibilities of directing people to the love of God. If the layout and decor are made appropriate to that of a beautiful coffee shop and subtly and incorporating traditional ideas of harmony and proportion, and colour harmony then it will be another aspect of the wider culture that will stimulate the liturgical instincts of those who attend. (I have described how that can be done in the context of a retail outlet in an appendix of The Little Oratory.) We should bare in mind Pope Benedict's words from Sacramentum Caritatis (71):

'Christianity's new worship includes and transfigures every aspect of life: "Whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God." (1Cor 10:13) Here the instrinsically eucharistic nature of Christian life begins to take shape. The Eucharist, since it embraces the concrete, everyday existence of the believer, makes possible, day by day, the progressive transfiguration of all those called by grace to reflect the image of the Son of God (cf Rom 8:29ff). There is nothing authentically human - our thoughts and affections, our words and deeds - that does not find in the sacrament of the Eucharist the form it needs to be lived in the full.'

So Jo Brand, we'll put away the bread knife and offer the bread instead!

Step one seems to be...first get your coffee shop. Anyone who thinks they can help us here please get in touch and we'll make it happen!

My friend Stratford Caldecott died very recently of cancer. I heard the news at a time that I was was reading his newly published book, Not as the World Gives: the Way of Creative Justice.

Contained within the book, which focusses for a large part on Catholic social teaching, especially in the light of Pope Benedict's Caritas in Veritate, he has a chapter on the evangelization of the culture. Within this, in turn, he makes a call for a new chivalry (p145):

My friend Stratford Caldecott died very recently of cancer. I heard the news at a time that I was was reading his newly published book, Not as the World Gives: the Way of Creative Justice.

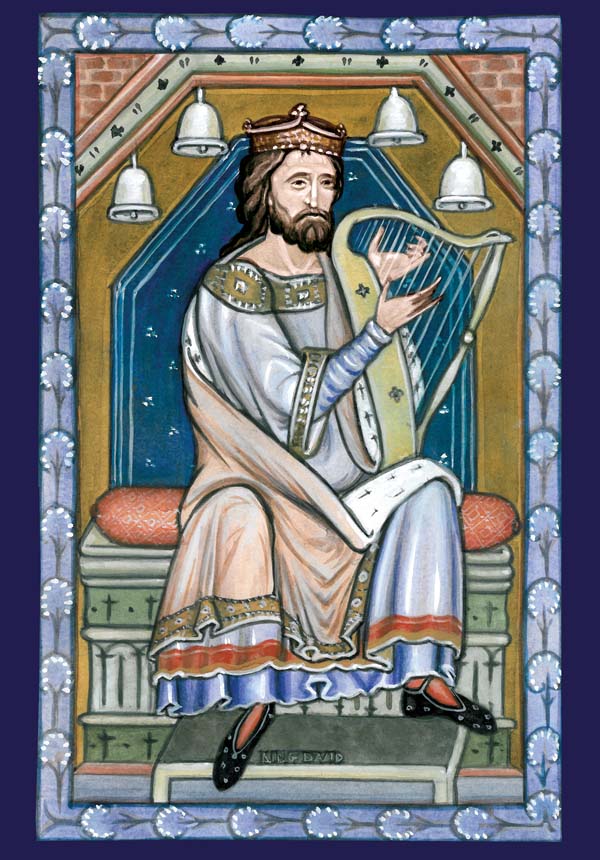

Contained within the book, which focusses for a large part on Catholic social teaching, especially in the light of Pope Benedict's Caritas in Veritate, he has a chapter on the evangelization of the culture. Within this, in turn, he makes a call for a new chivalry (p145): It was pure coincidence that this is the image that we were studying when I heard of Strat's death and then happened to read the above passage in his book.

It was pure coincidence that this is the image that we were studying when I heard of Strat's death and then happened to read the above passage in his book.

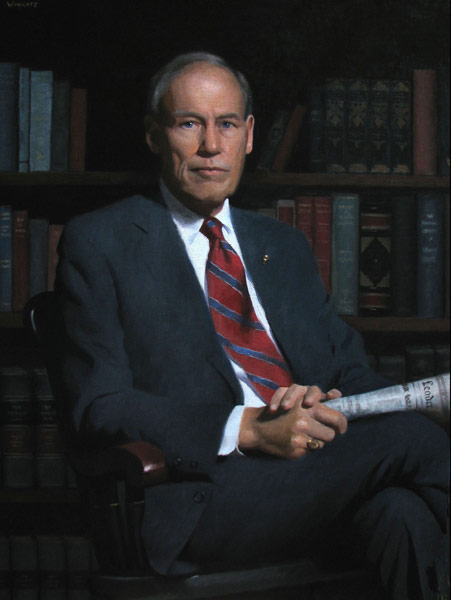

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)