There have been a number of articles published recently, following a show in Moscow, of carved icons of a Russian couple Rashid and Inessa Azbuhanov (their website is here and h/t Deacon Paul Iacono of the Fra Angelico Institute for bring these to my attention). These are exquisite works and are of interest to me particularly because I have to admit I have never seen anything quite like them. I am told that they are re-establishing the tradition of carved icons. These portray form through a combination of color and relief and in this sense are a halfway house between pure relief carving, which uses shadow to describe form; and the painted icon that we are used to.

This presentation of course would be easily used for Western styles and I can see it very quickly adapted gothic style imagery and for the Western variants of the iconographic tradition, such as the Celtic. I would love to see some Catholic artists somewhere taking up the idea.

This does raise the question in my mind (playing devils advocate here, as to why they bother? Is there any need for such a medium? I don't think that we should do something just for the sake of being different; but on the other hand should there be a compelling reason for in order to justify it? Isn't this just gilding the lily, so to speak?

I think that the answer is that provided the image is beautiful and works within the limits that define the tradition, then the greater the variety the better. Each tradition must contain within it the principles that allow the creation of new works, even new variants on the style, so that artists speak afresh to each new generation. Any tradition that relies only on reworking or reproduction of the past will dies. It seems to me that it would be like asking why, given the idea that we have trees in the natural world, did God create so many varieties? For me, it is the fact that so many varieties, beyond counting, can exist and participate in unique ways the same order that makes all things beautiful and direct us to the Creator. If this is so, then it does mean that we should be open to new materials and media as much as a variety of traditional ones, so that would include, for example artificial pigments as much as natural ones (other things being equal). This latter point, incidentally, is not a new one in his book on architecture from the 1st century AD the Roman architect Vitruvius has a section devoted to a comparison of the relative merits of natural and artificial pigments!

So here are some images: St Michael the Archangel, Kazan Mother of God, St John the Forerunner (the Baptist).

There have been a number of articles published recently, following a show in Moscow, of carved icons of a Russian couple Rashid and Inessa Azbuhanov (their website is here and h/t Deacon Paul Iacono of the Fra Angelico Institute for bring these to my attention). These are exquisite works and are of interest to me particularly because I have to admit I have never seen anything quite like them. I am told that they are re-establishing the tradition of carved icons. These portray form through a combination of color and relief and in this sense are a halfway house between pure relief carving, which uses shadow to describe form; and the painted icon that we are used to.

This presentation of course would be easily used for Western styles and I can see it very quickly adapted gothic style imagery and for the Western variants of the iconographic tradition, such as the Celtic. I would love to see some Catholic artists somewhere taking up the idea.

This does raise the question in my mind (playing devils advocate here, as to why they bother? Is there any need for such a medium? I don't think that we should do something just for the sake of being different; but on the other hand should there be a compelling reason for in order to justify it? Isn't this just gilding the lily, so to speak?

I think that the answer is that provided the image is beautiful and works within the limits that define the tradition, then the greater the variety the better. Each tradition must contain within it the principles that allow the creation of new works, even new variants on the style, so that artists speak afresh to each new generation. Any tradition that relies only on reworking or reproduction of the past will dies. It seems to me that it would be like asking why, given the idea that we have trees in the natural world, did God create so many varieties? For me, it is the fact that so many varieties, beyond counting, can exist and participate in unique ways the same order that makes all things beautiful and direct us to the Creator. If this is so, then it does mean that we should be open to new materials and media as much as a variety of traditional ones, so that would include, for example artificial pigments as much as natural ones (other things being equal). This latter point, incidentally, is not a new one in his book on architecture from the 1st century AD the Roman architect Vitruvius has a section devoted to a comparison of the relative merits of natural and artificial pigments!

So here are some images: St Michael the Archangel, Kazan Mother of God, St John the Forerunner (the Baptist).

Icon. Kazan Mother of God

Icon. John the Baptist

.jpg)

City parks and gardens derive their beauty as much from the public art as they do from the plants grown. Public art, of course has a greater impact also in those areas where there is no cultivation and Trafalgar Square in London is made by the Lions and Nelson's column as well as the beauty of the buildings on it. There is a plinth on in the corner of Trafalgar Square and that is always given to a piece of contemporary art which changes regularly. The latest fiasco to occupy this spot is time a giant purple cockerel that looks as though its made out of resin. What an absurdity! The scale of a piece of art speaks of its importance - the huge size of this, and its garish unnatural colour make it dominate the whole square, clashing with the otherwise harmonious arrangement of the other works in the square and working contrary to the natural hierarchy, in which cockerels come below man.

City parks and gardens derive their beauty as much from the public art as they do from the plants grown. Public art, of course has a greater impact also in those areas where there is no cultivation and Trafalgar Square in London is made by the Lions and Nelson's column as well as the beauty of the buildings on it. There is a plinth on in the corner of Trafalgar Square and that is always given to a piece of contemporary art which changes regularly. The latest fiasco to occupy this spot is time a giant purple cockerel that looks as though its made out of resin. What an absurdity! The scale of a piece of art speaks of its importance - the huge size of this, and its garish unnatural colour make it dominate the whole square, clashing with the otherwise harmonious arrangement of the other works in the square and working contrary to the natural hierarchy, in which cockerels come below man. If is commonly held that working conditions in 19th century cities were much worse than those who lived and worked in the countryside at the time or earlier; similarly you will regularly hear that the creation of factories split up families because the father had to go to work for so many hours every day whereas previously they had seen much more of him. When I questioned the basis of this once with some, the answer I got was that 'Charles Dickens proved it'. This was not a satisfactory answer to me - even if his picture portrayed in his novels is accurate it represents at best anecdotal evidence. It would be foolish, I suggest, to draw any conclusions about the general situation at this period only by consideration of works of fiction written for popular consumption. It does not give us facts and figures that might indicate what living standards were actually like during the 19th century; how conditions in the cities compared to those in the country; and how those conditions compared to the those of the previous century.

For an alternative view i looked to Capitalism and the Historians. This is a series of essays by economic historians who conclude that under capitalism in the 19th century, despite long hours and other hardships of factory life, people were in fact better off financially, had more opportunities to better themselves financially, had better living conditions and lived a life more supportive of the family life than those who lived in the country.

If is commonly held that working conditions in 19th century cities were much worse than those who lived and worked in the countryside at the time or earlier; similarly you will regularly hear that the creation of factories split up families because the father had to go to work for so many hours every day whereas previously they had seen much more of him. When I questioned the basis of this once with some, the answer I got was that 'Charles Dickens proved it'. This was not a satisfactory answer to me - even if his picture portrayed in his novels is accurate it represents at best anecdotal evidence. It would be foolish, I suggest, to draw any conclusions about the general situation at this period only by consideration of works of fiction written for popular consumption. It does not give us facts and figures that might indicate what living standards were actually like during the 19th century; how conditions in the cities compared to those in the country; and how those conditions compared to the those of the previous century.

For an alternative view i looked to Capitalism and the Historians. This is a series of essays by economic historians who conclude that under capitalism in the 19th century, despite long hours and other hardships of factory life, people were in fact better off financially, had more opportunities to better themselves financially, had better living conditions and lived a life more supportive of the family life than those who lived in the country. Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is

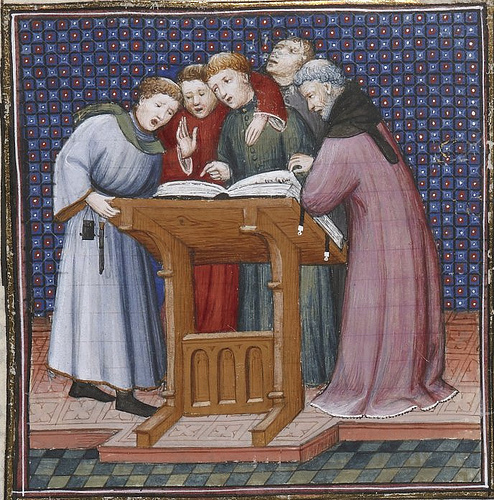

Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is

This summer we held a painting course in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. I taught it and it was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. This one is a St Christopher painted by a master of the school called Matthew Paris.

The students, Paul Jentz and his mother Christi (who kindly took and sent me the photographs) worked from the image shown top left. They constructed a grid as a help but drew the design by hand. While giving them guidance, I gave each freedom to vary the border and the colour schemes. I think you'll agree that they did a good job.

This summer we held a painting course in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. I taught it and it was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. This one is a St Christopher painted by a master of the school called Matthew Paris.

The students, Paul Jentz and his mother Christi (who kindly took and sent me the photographs) worked from the image shown top left. They constructed a grid as a help but drew the design by hand. While giving them guidance, I gave each freedom to vary the border and the colour schemes. I think you'll agree that they did a good job. .

.