Demonstrating the contrast been portraiture and the baroque style of sacred art. I have written in the past about the different approaches to portraiture and sacred art in the Western naturalistic form of the baroque (in the article: Is Some Modern Sacred Art too Naturalistic?) . I this I discussed the fact that many examples of sacred art are painted as though they are portraits and end up looking like a staged tableau in which the boy or girl nextdoor is dressed up in old fashioned clothing. Consider the work of someone I met when I was studying the academic method in Florence, Matthew James Collins. I know of know one else who knows more about the art of the baroque and High Renaissance periods. Matt is an American who still lives and works in Italy. His portfolio ishere (look at his sculpture and landscapes of the Italian countryside too)

I was looking at this portfolio a few days ago and several paintings of faces caught my eye. First this portrait left. It has all the right elements: it is painted in some areas loosely, and in some with more detail and tighter control, but always with precision. The variation in focus and colour content reflect the Christian understanding of the human person: those areas that we look at most, especially the eyes and the mouth, and which reveal emotion and thought and aspects of the soul, are those we look at the most when we look at someone. These are the parts that contain the most detail and the most natural colouring.

Demonstrating the contrast been portraiture and the baroque style of sacred art. I have written in the past about the different approaches to portraiture and sacred art in the Western naturalistic form of the baroque (in the article: Is Some Modern Sacred Art too Naturalistic?) . I this I discussed the fact that many examples of sacred art are painted as though they are portraits and end up looking like a staged tableau in which the boy or girl nextdoor is dressed up in old fashioned clothing. Consider the work of someone I met when I was studying the academic method in Florence, Matthew James Collins. I know of know one else who knows more about the art of the baroque and High Renaissance periods. Matt is an American who still lives and works in Italy. His portfolio ishere (look at his sculpture and landscapes of the Italian countryside too)

I was looking at this portfolio a few days ago and several paintings of faces caught my eye. First this portrait left. It has all the right elements: it is painted in some areas loosely, and in some with more detail and tighter control, but always with precision. The variation in focus and colour content reflect the Christian understanding of the human person: those areas that we look at most, especially the eyes and the mouth, and which reveal emotion and thought and aspects of the soul, are those we look at the most when we look at someone. These are the parts that contain the most detail and the most natural colouring.

If you look at the right side of the face, the part that in this portrait is more distant than the other. To make this read properly, the artist must make everything on this side of the face slightly smaller than the left; and the right edge must be blurred enough to give a sense of a turning edge, but still sharp enough to retain the right sense of contrast with the background. This is terrifically difficult to get right - even Titian and Rembrandt (for the most part absolute Masters) got it wrong occasionally. In this portrait Matt has captured it. Notice how even the glint on each eye varies to reflect the slight perspective - the right eye is more distant and the glint is smaller and less bright. These tiny specks of white can make or break a portrait.

Part of the essence of the baroque style is a strong emphasis on tonal description and the reduction of natural colour in all but the main focal points of the painting. Even if you master this, which is hard enough, then there is very often a problem in that the shadow areas look flat and dull. Matt has introduced some energy into the shadow by using a different of colours in any one area that are, broadly speaking, tonally equivalent (ie if you took a black and white photo there would be very little contrast) but of slightly different colours. This gives life and variety to the composition.

Notice also how he varies the background tone in order to enhance local contrast, so next to some dark edges of the head the background is slightly lighter and the opposite for light edges. However, he does so while avoiding a distracting, exaggerated patchiness and maintaining a unified impression.

It is an exceptional portrait, in my opinion. But the focus on the individual that we see here and is necessary in portraits would not be appropriate for sacred art. And this is the difficulty for many artists today who are trained primarily as portrait painters.

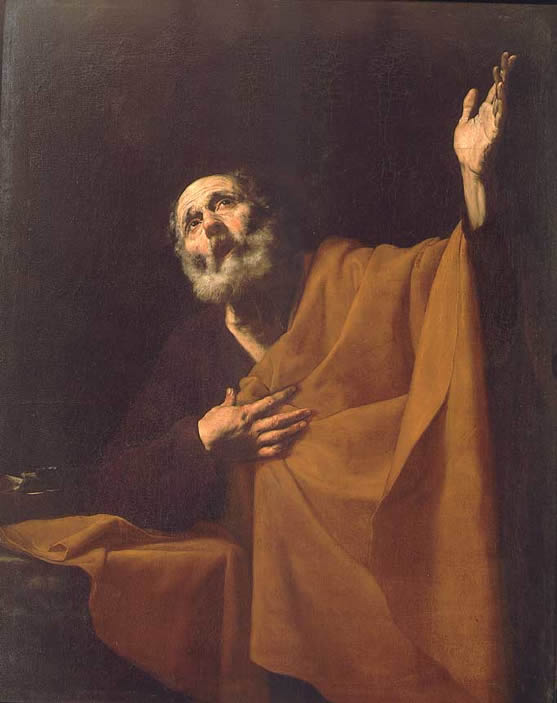

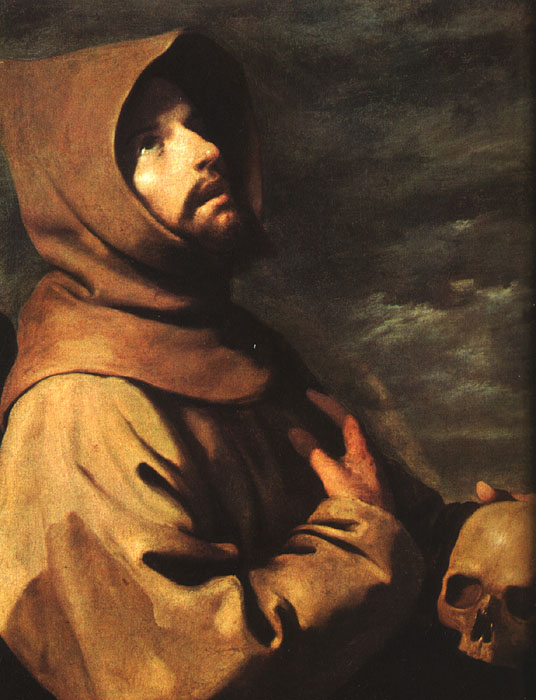

Contrast it with the first head study shown below. All the essentials elements are here too and handled just as well. However, this is not a portrait. It is one of a series of studies that Matt is doing to develop his skill in allegorical or explicitly sacred art. Matt has deliberately chosen to lessen the portrait elements of the face. This is the same device used by the baroque masters of the 17th century to paint the faces of saints. It causes to focus less on the individual, and more on those general characteristics that are common to all of us but are exemplified in an exceptional way in saints. Again this is difficult to do: it is a question of a shift of emphasis, rather than featuring one aspect to the exclusion of the other). Think of any of the paintings of St Francis of Assisi by the Spanish baroque painter Zurburan. The psychological aspects are communicated through posture and gesture as much as facial expressions but if this is overdone, the result is sentimentality, or even melodrama. This emphasis on the general can be seen, for example, one of the most famous pieces of sacred art produced in the 17th century, by Velazquez. The face of Christ is in shadow and is clearly very different from a portrait (I have put a detail of the face from this painting at the bottom.)

Matt does not have a large portfolio of sacred art to point to at the moment. He is a working artist with a young family portraiture and landscape are his staples. He mentioned to me ruefully, that even when people do commission sacred art, they want the 19th century style and so most of his sacred art has more of this negative aspect than he would choose to paint if he was not painting for sale.

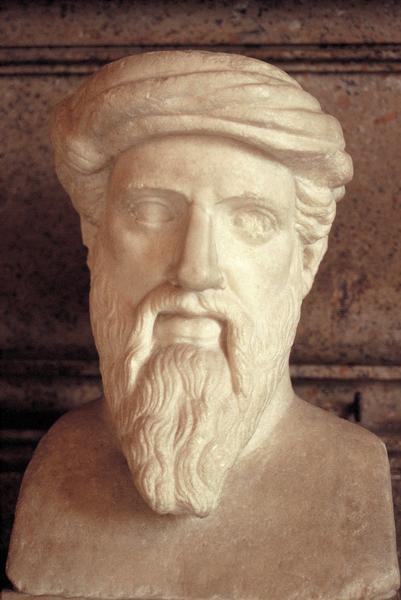

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work.

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work.

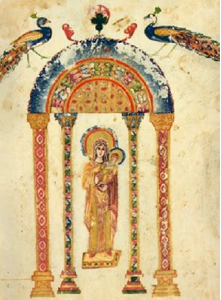

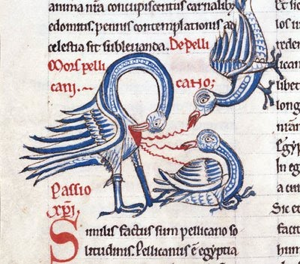

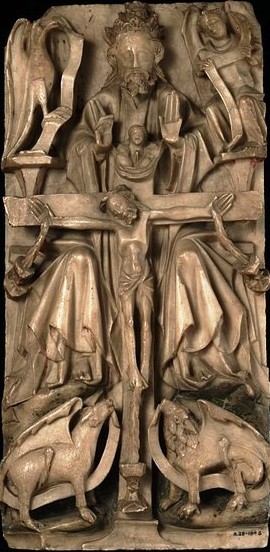

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

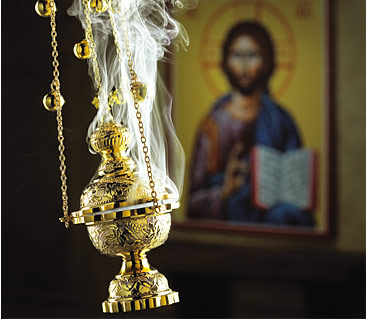

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

The Liturgy is the most powerful and effective form of prayer.

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III,  If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation. Chant:

Chant: Incorporating the sense of smell

Incorporating the sense of smell