‘Whatever experience comes your way, accept it as a blessing, in the certainty that nothing can happen without God’ Letter attributed to Barnabas, Ch 19

I am a convert. There are of course, many reasons that I became a Catholic, but an important one was the conviction that I would lead a happier life if I did. (I’m talking about this life, the here-and-now as much as the hereafter.)

‘Whatever experience comes your way, accept it as a blessing, in the certainty that nothing can happen without God’ Letter attributed to Barnabas, Ch 19

I am a convert. There are of course, many reasons that I became a Catholic, but an important one was the conviction that I would lead a happier life if I did. (I’m talking about this life, the here-and-now as much as the hereafter.)

One of the most influential figures in my conversion was a man called David who insisted that Christian joy comes as a result of the personal choices we make and is open to anyone. He taught me also how to cultivate Christian joy. David, incidentally, is the same person who gave me the vocational guidance that I have referred to before, here, and which rests so much on an assumption that God wants us to be happy. I was prepared to listen to him because he genuinely seemed a joyful person to me; and this was despite the fact that he had a heart condition that meant he could not walk without a stick and had to rest to catch his breath every 50 yards. The example of joy in adversity was powerful.

I have been reminded of David and his lessons of over 20 years ago now recently through readings from the liturgy of the hours. The things that he said to me about the joy of the Catholic life seem to me to be echoed in three readings I noticed this summer. This reinforces the for me just how powerful the liturgy is in educating and forming the person.

There are a number of aspects to cultivating joy of course, but one powerful contributor was a simple meditation called ‘counting my blessings’. Each day, he suggested, I should write down the good things that have happened that day – a ‘Gratitude List’ - and then as part of my daily prayers, thank God for these gifts. He was insistent that actually writing them down was important.

When I first met him I was miserable and not grateful for very much at all. He wrote out my first Gratitude List for me, which at this stage consisted of things I ought to be grateful for rather than things that I actually felt grateful for. I remember him starting with the basic necessities: he asked me first if I had eaten that day, then he wrote down ‘food’; then he looked at me and noted that I was clothed, and wrote ‘clothes’ on the list. ‘Do you have somewhere to sleep tonight?’ he asked me. When I answered yes he wrote to down, ‘Bed to sleep in’; and then he asked, is this outside or indoors? He wrote down ‘roof over my head’. Then he paused: ‘You have affirmed to me that each item on this list is true. So here you have written proof that this morning when you asked God to look after you today, he answered your prayer.’ He also told me that these things’ put me ahead’ of a significant proportion of the world’s population who didn’t know where their next meal was to come from. ‘Therefore,’ he said, ‘You really don’t have any good reason for complaining about your lot.’

When I first met him I was miserable and not grateful for very much at all. He wrote out my first Gratitude List for me, which at this stage consisted of things I ought to be grateful for rather than things that I actually felt grateful for. I remember him starting with the basic necessities: he asked me first if I had eaten that day, then he wrote down ‘food’; then he looked at me and noted that I was clothed, and wrote ‘clothes’ on the list. ‘Do you have somewhere to sleep tonight?’ he asked me. When I answered yes he wrote to down, ‘Bed to sleep in’; and then he asked, is this outside or indoors? He wrote down ‘roof over my head’. Then he paused: ‘You have affirmed to me that each item on this list is true. So here you have written proof that this morning when you asked God to look after you today, he answered your prayer.’ He also told me that these things’ put me ahead’ of a significant proportion of the world’s population who didn’t know where their next meal was to come from. ‘Therefore,’ he said, ‘You really don’t have any good reason for complaining about your lot.’

This was over 20 years ago and since then, pretty much daily, I have been writing a gratitude list. To this list of necessities, I always add half a dozen or so ‘luxuries’: the things that I have received that a more than what need. So any through this I thank God as well for any other positives in the day, major or minor. Pretty soon, perhaps after about a month or so, I noticed that I genuinely felt grateful for these things. But the benefits went further than that. The result for me has been to reinforce the faith in a loving God who is actively looking after me. There has never been a day when I haven’t been given all that I need.

This does seem to leave gaps though. It’s one thing to appreciate the good things, but another to accept the bad things and still be happy. I have had to deal with many of the setbacks and disappointments that one would expect in an ordinary life. They way I deal with these is to remember something else that David told me. That if we assume that a loving God is working in my life and wants me to be happy, then I should remember that all that happens is either willed by God directly, or if it is bad, is permitted by God for good reason. (God, who is all goodness cannot be the author of something that is bad.) This means that if I could see the bigger picture then I would be able to see what this greater good was but because I am not able to I can have faith that there is a greater good nevertheless. Perhaps it is a lesson learnt for the good of my soul, or it is directing me down a path that will reap greater rewards later. In order to help cultivate gratitude for these bad things, David used to put them on his gratitude list too and praise God for them, on the grounds that even these must be permitted by a God who had his best interests at heart. I have adopted his habit and have found this powerful in helping to intensify a faith in a loving God.

This last point was reinforced by two quotations in the Liturgy recently.

From Office of Readings, Wednesday Week 18 of the Year, Letter attributed to Barnabus, Ch 19: ‘Whatever experience comes your way, accept it as a blessing, in the certainty that nothing can happen without God.’

From Office of Readings, Wednesday Week 18 of the Year, Letter attributed to Barnabus, Ch 19: ‘Whatever experience comes your way, accept it as a blessing, in the certainty that nothing can happen without God.’

From Lauds, Wed, Week II, Romans 8:35, 37: 'Nothing can come between us and the love of Christ, even if we are troubled or worried, or being persecuted, or lacking food or clothes, or being threatened or even attacked. These are the trials through which we triumph, by the power of him who loved us.'

Despite the success of this tool in my own life, it still doesn’t go far enough, I think. In many ways I have led a privileged life and haven’t had to face extreme suffering. This little technique might be good for the everyday ups and downs of everyday life, but does this idea apply to those who suffer torture, or who went through the Nazi concentration camps. This is where the study of the lives of the saints paid dividends for me. I studied the writing of saints who had been through such things and was struck by the joy they talk about even in such adversity. It seems that God’s grace really can overcome anything. I should state at the same time, I am very far from ready to volunteer for such suffering. However, the more I read passages such as the one that follows, the more it reinforces the idea that whatever the situation there is sufficient grace, if I cooperate, for me to overcome it.

From Office of Readings, June 22nd, a letter written by St Thomas More to his daughter Margaret from prison: 'Although I know well, Margaret, that because of my past wickedness I deserve to be abandoned by God, I cannot but trust in his merciful goodness. His grace has strengthened me until now and made me content to lose goods, land, and life as well, rather than to swear against my conscience. God’s grace has given the king a gracious frame of mind toward me, so that as yet he has taken from me nothing but my liberty. In doing this His Majesty has done me such great good with respect to spiritual profit that I trust that among all the great benefits he has heaped so abundantly upon me I count my imprisonment the very greatest. I cannot, therefore, mistrust the grace of God. Either he shall keep the king in that gracious frame of mind to continue to do me no harm, or else, if it be his pleasure that for my other sins I suffer in this case as I shall not deserve, then his grace shall give me the strength to bear it patiently, and perhaps even gladly.

From Office of Readings, June 22nd, a letter written by St Thomas More to his daughter Margaret from prison: 'Although I know well, Margaret, that because of my past wickedness I deserve to be abandoned by God, I cannot but trust in his merciful goodness. His grace has strengthened me until now and made me content to lose goods, land, and life as well, rather than to swear against my conscience. God’s grace has given the king a gracious frame of mind toward me, so that as yet he has taken from me nothing but my liberty. In doing this His Majesty has done me such great good with respect to spiritual profit that I trust that among all the great benefits he has heaped so abundantly upon me I count my imprisonment the very greatest. I cannot, therefore, mistrust the grace of God. Either he shall keep the king in that gracious frame of mind to continue to do me no harm, or else, if it be his pleasure that for my other sins I suffer in this case as I shall not deserve, then his grace shall give me the strength to bear it patiently, and perhaps even gladly.

By the merits of his bitter passion joined to mine and far surpassing in merit for me all that I can suffer myself, his bounteous goodness shall release me from the pains of purgatory and shall increase my reward in heaven besides.

I will not mistrust him, Meg, though I shall feel myself weakening and on the verge of being overcome with fear. I shall remember how Saint Peter at a blast of wind began to sink because of his lack of faith, and I shall do as he did: call upon Christ and pray to him for help. And then I trust he shall place his holy hand on me and in the stormy seas hold me up from drowning.

And if he permits me to play Saint Peter further and to fall to the ground and to swear and forswear, may God our Lord in his tender mercy keep me from this, and let me lose if it so happen, and never win thereby! Still, if this should happen, afterward I trust that in his goodness he will look on me with pity as he did upon Saint Peter, and make me stand up again and confess the truth of my conscience afresh and endure here the shame and harm of my own fault.

And finally, Margaret, I know this well: that without my fault he will not let me be lost. I shall, therefore, with good hope commit myself wholly to him. And if he permits me to perish for my faults, then I shall serve as praise for his justice. But in good faith, Meg, I trust that his tender pity shall keep my poor soul safe and make me commend his mercy.

And, therefore, my own good daughter, do not let your mind be troubled over anything that shall happen to me in this world. Nothing can come but what God wills. And I am very sure that whatever that be, however bad it may seem, it shall indeed be the best.'

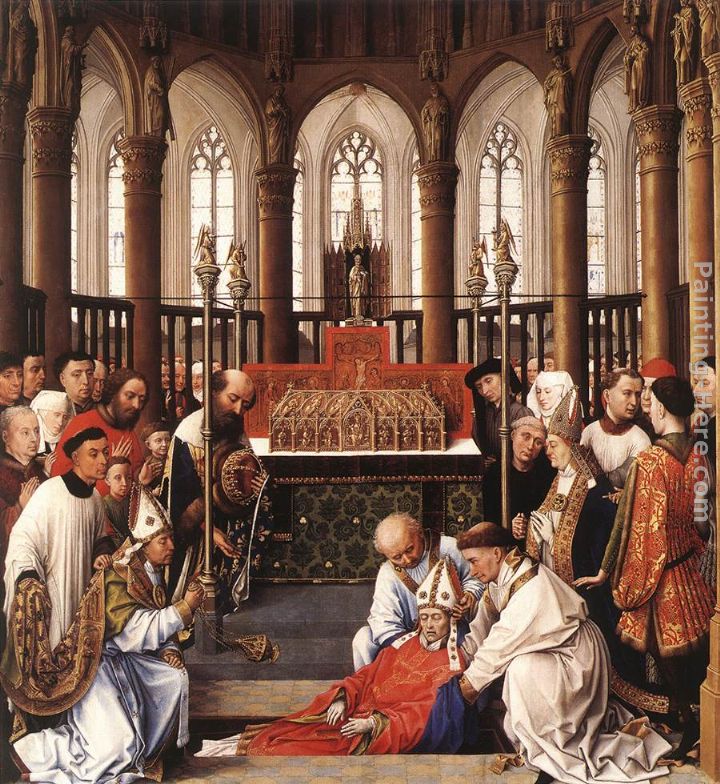

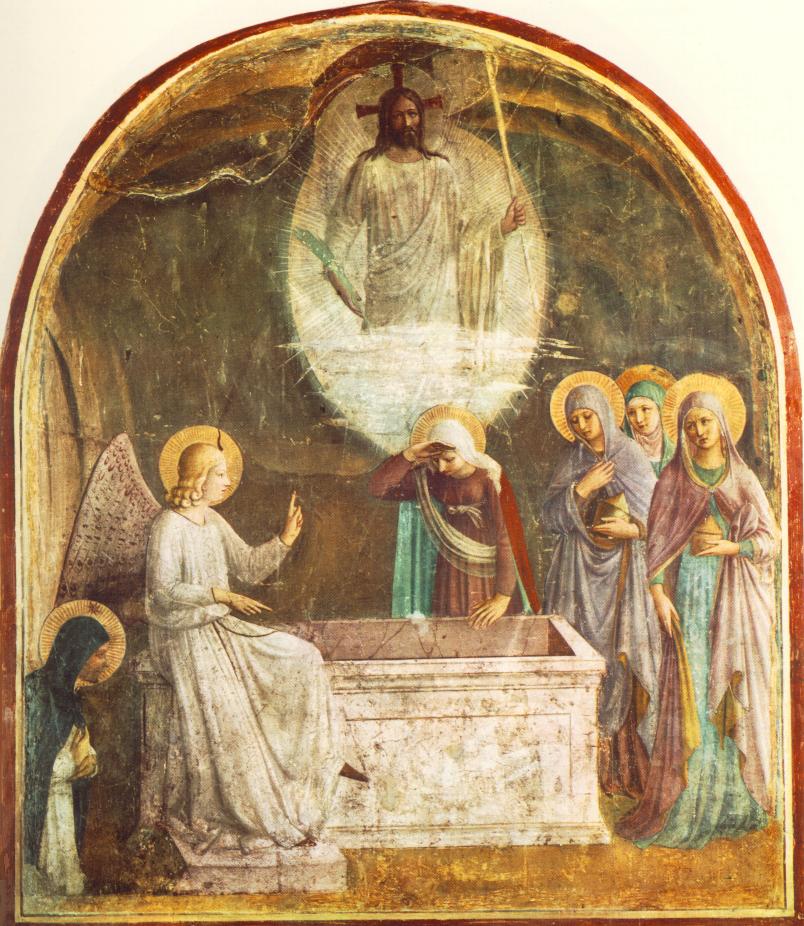

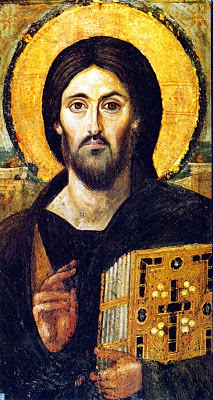

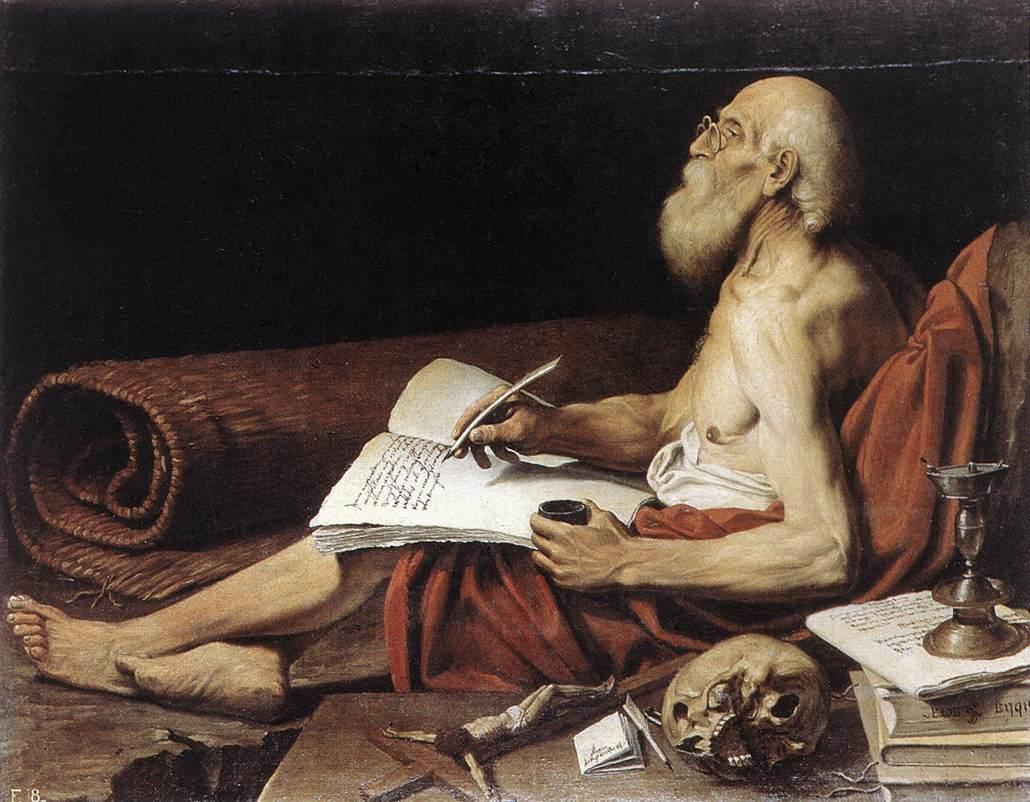

Images: Nicolaes Berchem, St Paul and St Barnabas Preaching at Lystra, 17th century. St Paul, ancient wall painting; St Barnabus, Rembrandt, 17th century; St Thomas More, polychrome statue at St Thomas More parish, Pottsdown, Pennsylvania. Below: Hans Holbein' drawing of the More

Featuring Peter Kreeft, Fr Peter Stravinskas and Dr William Fahey of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. The Anglican Use Congregation of St. Athanasius and the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston will be sponsoring a symposium on the feast of Blessed John Henry Newman on Sunday, October 9, 2011 at 3 p.m. at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. There will be a series of well known speakers in the afternoon Peter Kreeft, Philip Crotty, Fr Peter Stravinskas and President of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, William Fahey.

There will be a reception and then Choral Evensong at 5pm. Choral Evensong is especially to be recommended for any who wish to see a model of beautiful and dignified liturgy in the vernacular.

Featuring Peter Kreeft, Fr Peter Stravinskas and Dr William Fahey of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. The Anglican Use Congregation of St. Athanasius and the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston will be sponsoring a symposium on the feast of Blessed John Henry Newman on Sunday, October 9, 2011 at 3 p.m. at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. There will be a series of well known speakers in the afternoon Peter Kreeft, Philip Crotty, Fr Peter Stravinskas and President of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, William Fahey.

There will be a reception and then Choral Evensong at 5pm. Choral Evensong is especially to be recommended for any who wish to see a model of beautiful and dignified liturgy in the vernacular.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.

Similarly, the artist must try to consider the wider context into which it is to be placed. Works look different when placed on dark or light backgrounds, or when there are other paintings around. Also and most importantly, the position relative to the liturgy must be considered.

Where had the inspiration for this come from, I asked? I expected to be told that this was part of the American neo-gothic inspired first by figures such as Pugin in England. To my surprise I was told that the inspiration came from American quilt patterns. I had been told before (though hadn’t really bothered to investigate further) that what I was looking at was similar to many traditional quilt patterns. I don’t know much about the history of these quilt patterns, but it has occurred to me that just as with Islam, a protestant society that has iconoclastic instincts is going develops its artistic expression in geometric non-fugurative areas. So perhaps we have here another source inspiration for us in trying to reestablish geometric patterned art as part of the Catholic tradition. As with all these things, it should be done (with discernment - I wouldn't always retain the colour schemes used!) but there do seem to me to be possibilities here.

Where had the inspiration for this come from, I asked? I expected to be told that this was part of the American neo-gothic inspired first by figures such as Pugin in England. To my surprise I was told that the inspiration came from American quilt patterns. I had been told before (though hadn’t really bothered to investigate further) that what I was looking at was similar to many traditional quilt patterns. I don’t know much about the history of these quilt patterns, but it has occurred to me that just as with Islam, a protestant society that has iconoclastic instincts is going develops its artistic expression in geometric non-fugurative areas. So perhaps we have here another source inspiration for us in trying to reestablish geometric patterned art as part of the Catholic tradition. As with all these things, it should be done (with discernment - I wouldn't always retain the colour schemes used!) but there do seem to me to be possibilities here.

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at

Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is pleased to announce that once again that undergraduates, the college's Guild of St Luke will be able to attend a weekly, day-long course in academic drawing at

By Fr Michael Fones OP

By Fr Michael Fones OP  charism by trying to teach someone *something* – like chemistry, or how to kick a soccer ball, for example. How did I feel while I was teaching? Did the individual learn? What kind of feedback did I receive?

charism by trying to teach someone *something* – like chemistry, or how to kick a soccer ball, for example. How did I feel while I was teaching? Did the individual learn? What kind of feedback did I receive?

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...

The Way of Beauty Atelier has completed the two-week workshops in both naturalistic drawing and icon painting

The Way of Beauty Atelier has completed the two-week workshops in both naturalistic drawing and icon painting