Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one, here) I am not an expert in this at all, but I thought that my experiences of trying (and often failing) to learn the technique and practice it, might be a starting point for others who wish to make a beginning also. Also I would encourage any of you who have experience to offer any helpful thoughts for the benefit of the readership…

Before I even began my investigation of lectio divina, the point was made to me that it is good to go to someone who can structure my spiritual life so that all of these things have a unity that allow them to nourish and support my ordinary daily activities. The danger is that I just tack one more devotion onto the daily list of personal obligations without proper understanding of how it relates to the other things that I do and the whole thing becomes a burden, in which I feel guilty if don’t tick all the boxes that day.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one, here) I am not an expert in this at all, but I thought that my experiences of trying (and often failing) to learn the technique and practice it, might be a starting point for others who wish to make a beginning also. Also I would encourage any of you who have experience to offer any helpful thoughts for the benefit of the readership…

Before I even began my investigation of lectio divina, the point was made to me that it is good to go to someone who can structure my spiritual life so that all of these things have a unity that allow them to nourish and support my ordinary daily activities. The danger is that I just tack one more devotion onto the daily list of personal obligations without proper understanding of how it relates to the other things that I do and the whole thing becomes a burden, in which I feel guilty if don’t tick all the boxes that day.

Now for lectio divina itself: the first part is lectio. This just means reading. The first thing I have to do is select a passage to read. I was told to start with the gospels. If I aim to do it regularly, it was suggested that I try to go through the bible systematically, even if this means that it will take years to go through it once. One person told me another systematic approach to begin with is to pick the readings, or just the gospel reading, for Mass that day. If you don’t have a Missal to hand, www.universalis.com has the readings each day.

So having selected the passage I say a short prayer, that I might be receptive to whatever God wants to say to me through the passage I read. And then I read away. As phrases catch my attention I re-read. If nothing catches my attention, I just re-read the whole allotted passage a number of times. One helpful piece of advice given to me was that God will speak to me at the level I am at. So I shouldn’t worry that I am not a scripture scholar who isn’t instantly aware, for example, of the parallels between Old and New Testaments or the allegory that it contains, and so on.

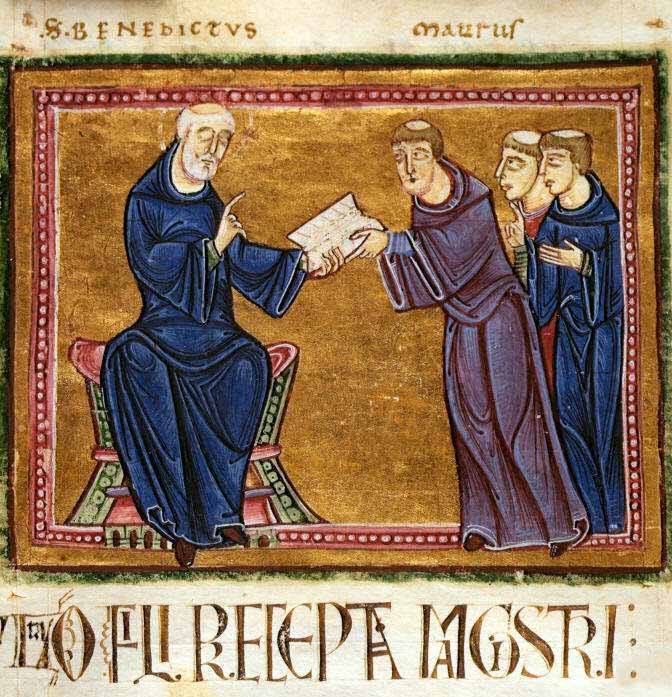

However, it is a good idea, I was told to support this lectio, if I have time, with reading of commentaries on scripture, that my understanding might increase in time. I was told to be careful with modern commentaries as many (including some by Catholic writers) do not adopt a starting postion of faith that this is the inspired Word, and so a skepticism creeps into their work. I play safe and go for the Church Fathers and even here I let the Church guide me through her liturgy. The Office of Readings has a passage every day by a Church Father and very often this is a commentary on scripture. So I let the Church educate me as I worship God the Father in the Liturgy. Here is this dynamic, described yesterday, of Liturgy illuminating Scripture and Scripture intensifying my participation in the Liturgy. Again, the Universalis website is a great source for the Office of Readings each day.

However, it is a good idea, I was told to support this lectio, if I have time, with reading of commentaries on scripture, that my understanding might increase in time. I was told to be careful with modern commentaries as many (including some by Catholic writers) do not adopt a starting postion of faith that this is the inspired Word, and so a skepticism creeps into their work. I play safe and go for the Church Fathers and even here I let the Church guide me through her liturgy. The Office of Readings has a passage every day by a Church Father and very often this is a commentary on scripture. So I let the Church educate me as I worship God the Father in the Liturgy. Here is this dynamic, described yesterday, of Liturgy illuminating Scripture and Scripture intensifying my participation in the Liturgy. Again, the Universalis website is a great source for the Office of Readings each day.

The second part is meditatio. This means ‘I think’. This was always a source of confusion for me. In this age of post-Beatles, Maharishi Yogi pop culture, I thought that meditating on a phrase meant repeating it like a mantra in Eastern meditation. And that the goal was one of the elimination of thought; or at the very least it was a passive process of just letting my mind drift in the ethereal breeze and see what thoughts might crop up, but without reacting to them. I couldn’t work out what I was supposed to be doing here – it seemed to be contradictory to the idea of trying to understand the passage, which involved the application of reason to what was being read. My predicament wasn’t help by many of the books that I first read about Lectio Divina. Some (perhaps influenced by pop culture too) read as though they had been written by a beatnik writer who described it as an invitation for me to indulge in my emotions through undirected random or stream-of-consciousness style thought, on the assumption that because I had just read a bit of the bible, this was God at work in my mental processes. I was suspicious of this undirected approach.

The way out of this changed when I was told something about the distinction between Christian and Eastern, non Christian, ideas of meditation. Meditate, in the Christian tradition means more ‘meditate upon’, the same as ‘think’. So while in meditatio I do pause and allow for the prompting of the Spirit in the form of occurring thoughts and ideas; when they do occur I react to them by mulling over them, perhaps asking myself: what does this mean? Is there something that applies to me directly? How can I act on this in the rest of the day? And so on.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

I find that once I start reading, I can move gently from one to the other, reading, thinking, saying a short prayer and then reading again.

The fourth part is contemplatio. This is contemplative prayer. As you can imagine, this originally caused me confusion too. I thought contemplation and meditation meant pretty much the same thing. And given the fact that I didn’t initially understand what meditation was, the inclusion of contemplation just compounded it even further. So I needed another explanation: in contrast to mediatio , this part is passive. It is passive in the sense that it is a state of mind that is given to us as a gift from God and actively pursuing it cannot guarantee its occurance. If I have understood the descriptions properly, it is a state of stillness of mind; one of just being with God and it sounds something like the descriptions of the beatific vision when we are in full union with God in heaven. However, as it is a gift from God, I should be careful in interpreting anything from about it or concluding anything about my spiritual development, or about how well I have done the first three stages. God either gives it to me or he doesn’t. Contemplation, therefore, is not a reward or goal of the first three stages, in that sense, it is just something that might happen, or it might not over which we have very little control. For myself, all I can say is that if it happened to me, I didn’t notice (which I’m guessing probably means that is hasn’t happened!).

The reason I do this is the reason that I am driven to do any of these things. I believe that ultimately and generally, I will be the happier for doing so, rather than any immediate reward of a pleasant emotion or feeling during the process.

At this point, I was going to include another passage from the Office of Readings at the end of this, but given the length of this piece so far, so I’ve decide d to tack on a Part Three, which will appear tomorrow. It is by the 3rd century Father, Ephraim the Syrian.

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow)

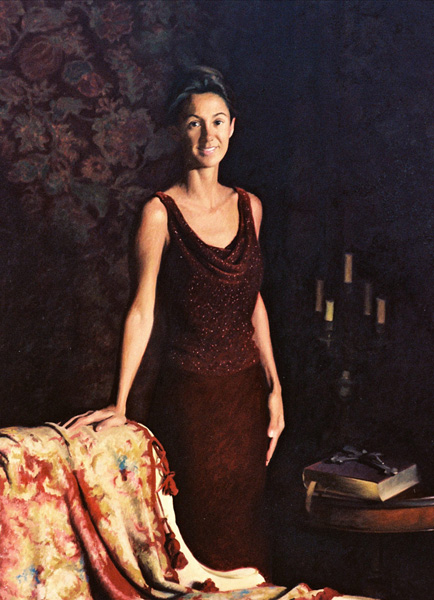

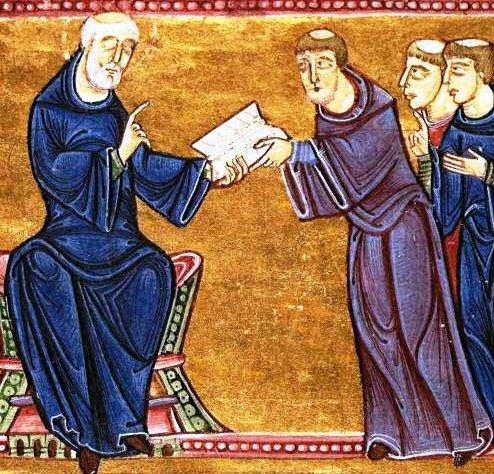

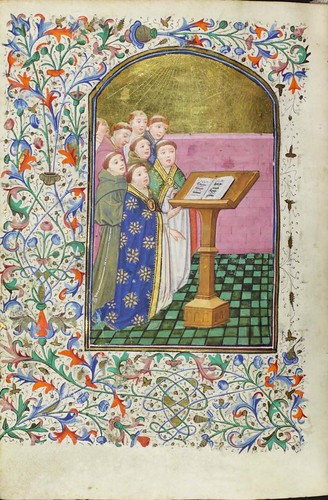

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow) Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

The tradition of the Eastern Church

The tradition of the Eastern Church