Prayer of the Heart - How to Engage the Whole Person in Prayer. The Divine Office III

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III, part II here, part I here.

Engaging the Whole Person in Prayer Opens us up Further to Inspiration and Creativity - The Divine Office III, part II here, part I here.

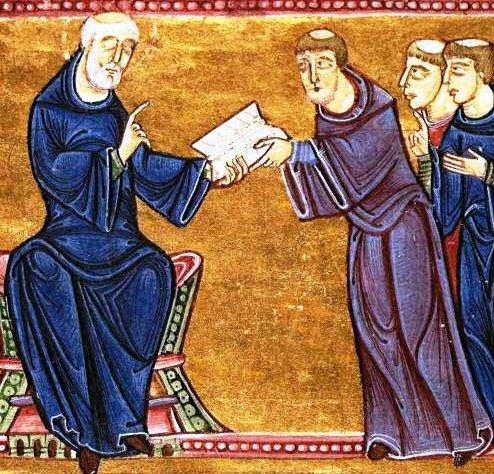

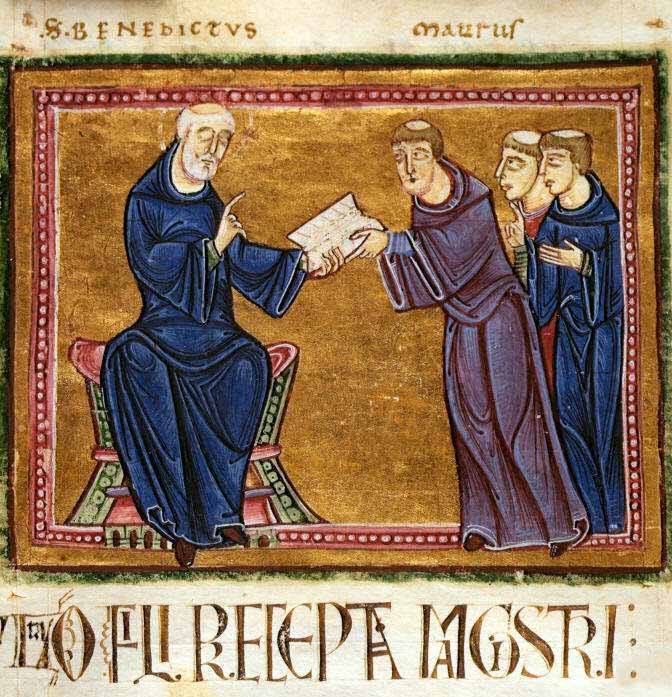

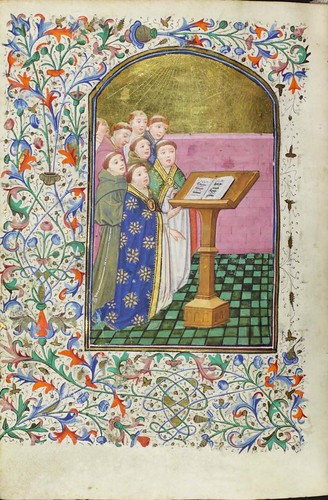

‘In the sight of angels I will sing praise to you (Ps 138:1). Let us rise in chanting that our hearts and voices harmonise.’ (Rule of St Benedict: Ch 19)

The heart is the human centre of gravity, our very core that incorporates both body and soul. It is the place that represents the whole person, the vector sum of all our actions and thoughts. If our hearts are to be in harmony with the prayers of the angels in heaven as St Benedict suggested, we need to consider not just our thoughts and voices, but our actions, our bodies and even how are senses are engaged in the action of prayer. The heart is also the place that is closest to God (considering both physical and spiritual human anatomy). It is closest in the sense of being that place that is most directly in contact with Him. So, if we seek the ideal stated, and harmonise our hearts with the prayer of the heavenly hosts, we will also be more sensitive to inspiration because the whole person is engaged. The Liturgy of the Hours is the means to continuous prayer, as discussed last week.  If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

If in the context of the Liturgy our continuous prayer simultaneously engages the whole person then can we are opening ourselves up to the greatest degree possible to God’s grace. To the degree that we cooperate with grace this will help us make all our life decisions and help us to move towards the fulfillment of our personal vocation in life. This will be perfectly ordered also to the model of charity, that is, love of God. To the degree that we match these standards there will be perfect harmony with the objective standard of God’s will. This is the supernatural path to inner peace, peace with our neighbour and a life in harmony with creation.

As I have said before, I don't claim to be an expert in these matters at all, but I can pass on the guidance that I was given when I asked about these things. Here are the things that were suggested to me a way of involving the whole person in prayer. I seek, as well as seeking to attune my thoughts to the prayer of the Liturgy, to engage all my senses and my physical being in the prayer too:

Chant: the use of voice (and hearing). Even if I do it on my own, I will sing the Office (quietly!). As an aside: ironically singing on my own regularly stopped me from being self conscious about singing in front of others. I was so used to hearing my own voice and not being unsettled by it, that in time the thought of others hearing it too didn’t worry me.

Chant: the use of voice (and hearing). Even if I do it on my own, I will sing the Office (quietly!). As an aside: ironically singing on my own regularly stopped me from being self conscious about singing in front of others. I was so used to hearing my own voice and not being unsettled by it, that in time the thought of others hearing it too didn’t worry me.

Posture: consider our posture at all times. In the Mass I try to follow the rubrics, and in the Liturgy of the Hours do my best to follow the traditional postures such as bowing, standing, sitting. Why is posture important? I see it like this: in the ideal every aspect of human nature is directed towards God, my actions and motives. At any time my motives for doing something are likely to be mixed and not perfectly pure. I have found that even if I don’t feel like praying or feel very peaceful, I can resolve to do it anyway and adopt a reverential posture. My body will tend to lead my heart in the right direction. And where my heart goes, my thoughts and feelings will follow suit. The following scheme was suggested to me and we try to follow this when we say the Office together at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts: we stand through opening words and hymn until the psalms are recited, when we sit, and we stand again for the gospel canticle until the close or if there is no gospel canticle we stand for the closing prayer ; we bow (and if sitting, say at the end of the psalm, we stand again) in honour of the Trinity for the last verse of each hymn and the glory be; we bow our heads at mention of the name Jesus.

Engaging our sense of sight: pray with visual imagery and use candles. I light candles to mark the time of prayer (it reminds me that Christ is the Light of the World) . If I pray to as named saint, for example, Our Lady, I turn and look at an image of her as I do so. At home I create and icon or image corner as a focus for prayer. This can be as simple as have a single icon, or become of more sophisticated combination of images changing according to season and day (see earlier article Praying with Visual Imagery). The ideal core imagery for and icon corner, in accordance with tradition, is to have a crucifixion in the centre, which portrays the suffering Christ; an image of Our Lady on the left; and an additional image of Our Lord glorified on the right. (See past article, How to Make an Icon Corner]

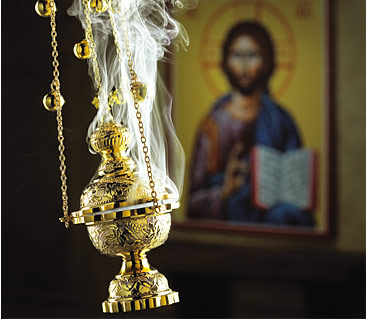

Incorporating the sense of smell –I was encouraged to use incense, for example when singing the gospel canticles. However, I was told, it should be used selectively in accordance with the hierarchy of the liturgy so everything together points to the Sunday Mass as it highpoint. So for example, in community incense can be used on Feast days and Solemnities at Vespers, Lauds and Compline (when gospel canticles are sung), but only if incense is also used at Sunday Mass.

Incorporating the sense of smell –I was encouraged to use incense, for example when singing the gospel canticles. However, I was told, it should be used selectively in accordance with the hierarchy of the liturgy so everything together points to the Sunday Mass as it highpoint. So for example, in community incense can be used on Feast days and Solemnities at Vespers, Lauds and Compline (when gospel canticles are sung), but only if incense is also used at Sunday Mass.

v) Incorporating taste and touch-the Eucharist. We do not take communion during the Liturgy of the Hours, but we should not forget the wider picture. I was reminded that the liturgy as a whole is seen as an unfolding of a single event that incorporates both the Hours and Mass, but has the Mass at its centre. The quotation given to me mentioned in an earlier article comes to mind again here: the Mass is a jewel in its setting, which is the Liturgy of the Hours; and the Liturgy of the Hours also has its setting, which is the cosmos.

Further articles;

The Four Pillars of the New Liturgical Movement

Those who want to learn to do the Divine Office, you might approach a priest or religious (ie monk or nun) and ask them to show you. Alternatively, the Way of Beauty summer retreats at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts will teach you how to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and how you can realistically incorporated it into a busy working or family life

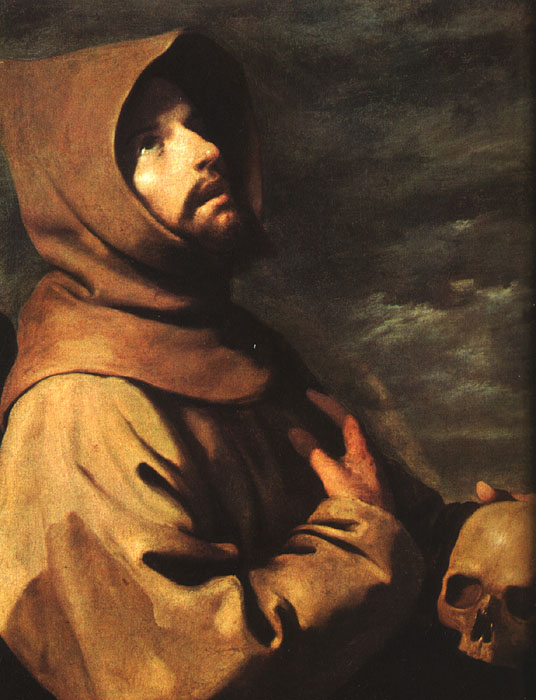

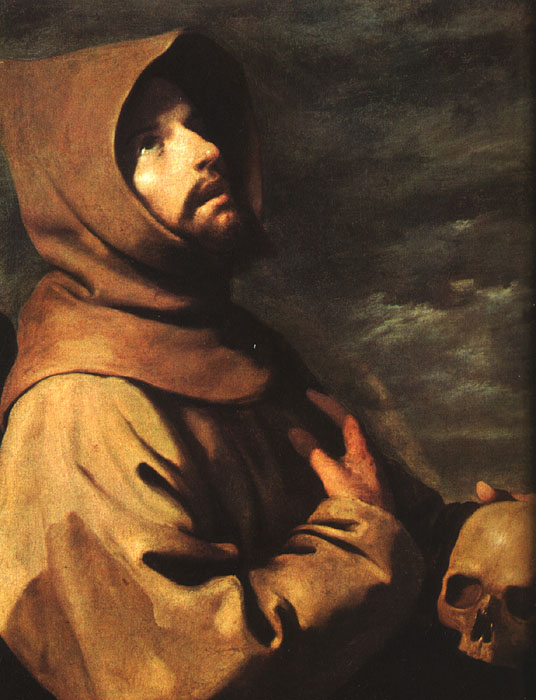

The Painting is of St Francis is by the 17th century Spanish artist Zurbaran

and, below, the Adoration of the Trinity by Albrecht Durer

The Brussels Academy of Icon Painting

As a postscript to the article about the work of Irina Gorbunova-Lomax, a reader has sent me information about two more websites with more up-to-date work of hers on display. You can see them here and here. I was also contacted by an old friend of mine from Oxford, a Catholic, who is studying with her. As ever, I am delighted to receive this additional information from readers and, in turn, happy to pass it on to you. Originally from the Ukraine, Irina studied in Russia. She is married to an Englishman and lives in Brussels (she is not based in France as I first thought). She runs a 4-year, part-time course in icon painting (38 three-hour lessons over this period). She is an excellent teacher by all accounts and, I was told, she is respectful of the Catholic Faith and many Catholics are already learning with her.

Details about her school, can be found at the Brussels Academy of Icon Paintingsite. Based upon the recommendations I have received and the quality of her work, any wishing to learn icon painting who can get to Brussels should consider her classes. The photos below are of her classes and exhibitions of student studies. The final picture of work by Irina.

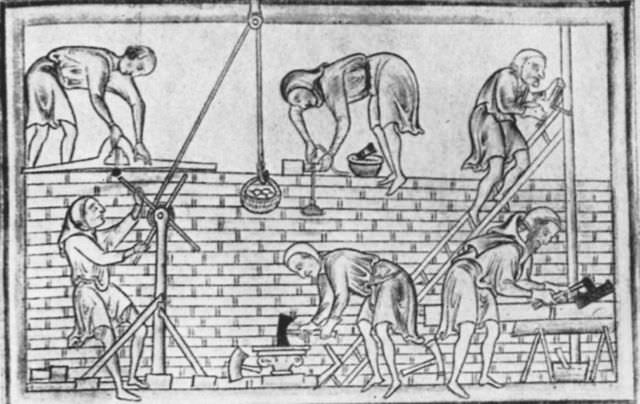

How all human work can be inspired - The Divine Office, II

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (part 1 is here):

St Paul exhorts us: ‘Always rejoice. Pray without ceasing.’ (1 Thessalonians 5:16-17).

How busy people can strive for the ideal of praying continuously. The Divine Office for lay people, part 2 (part 1 is here):

St Paul exhorts us: ‘Always rejoice. Pray without ceasing.’ (1 Thessalonians 5:16-17).

How can we do this? One can imagine the heavenly host of angels and saints doing this as they participate in the heavenly liturgy. But how can we, while here in this earthly life, strive towards this ideal? The answer is the liturgy of the hours, also known as the Divine Office.

The Church’s General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours reads as follows:

"Consecration of Time

10. Christ taught us: "You must pray at all times and not lose heart" (Lk 18:1). The Church has been faithful in obeying this instruction; it never ceases to offer prayer and makes this exhortation its own: "Through him (Jesus) let us offer to God an unceasing sacrifice of praise" (Heb 15:15). The Church fulfills this precept not only by celebrating the Eucharist but in other ways also, especially through the liturgy of the hours. By ancient Christian tradition what distinguishes the liturgy of the hours from other liturgical services is that it consecrates to God the whole cycle of the day and the night. [56]

11. The purpose of the liturgy of the hours is to sanctify the day and the whole range of human activity.'' [My emphasis]

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

If all times in the day and all human activity (no matter how mundane) can be sanctified by praying the liturgy of the hours, as the Church tells us, then this is this is a wonderful gift by which we can open ourselves up to God’s inspiration and consolation in all we do, and the degree that we cooperate, all our activities will be good and beautiful; and will be infused with new ideas and creativity. And we will have joy.

There are seven liturgical hours to be marked in the day and by tradition the process of doing something seven times symbolizes doing it perfectly or continuously. So for example, the psalmist (Ps 12:6) tells us that, ‘The words of the Lord are pure words: like silver tried by fire, purged from the earth refined seven times.’ This pattern of cycles of seven runs through the liturgy (see previous article, The Path to Heaven is a Triple Helix).

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

Even if we accept this and want to benefit from it, it is a huge problem for most lay people. If you get the full cycle of prayer of seven Offices in the day for seven days of every week in the year it adds up to a three or four volume set. Priests and religious who are obliged to pray it, devote a huge part of their lives to praying the liturgy of the hours. Benedictine monks can spend up to six hours a day singing the psalms in church. One might expect them to be able to cope as that is their special calling, but what about the rest of us?

This is how I approached the problem. First, as with all these things the help of a spiritual director is invaluable. He told me that I should take heart in the fact that through its priests and religious especially, the Church as a whole is praying the Hours on our behalf. As the globe turns, someone somewhere is praying for all of humanity (most of whom have no idea of the benefits they are getting as a result). So any additional contribution that I might make, no matter how small, to this prayer of Christ in the mystical body, the Church, will be good, but neither is everything going to collapse if I don't do it perfectly. Even one Hour (or ‘Office’) a week is worth it.

I was told to start modestly. If I found it beneficial, then I was told that I could increase what I did, but then it would be best to do so only gradually. There was a danger that if I took on too much too early that I would find it overwhelming and then give up altogether.

I started by aiming to read a maximum of two each day: Morning Prayer (‘Lauds’) when I got up and Night Prayer (‘Compline’) before I went to bed. I had a single volume version that just had Lauds, Evening Prayer (Vespers) and Compline for the year. If you want to try this but don’t even want to buy a book, you can see what each Office is for any day by going to www.universalis.com.

Mark the Hours

Mark the Hours

It took me a while to develop this habit, but once I had, I had to decide what to do next? I'd experienced enough to know that this was good and I knew I wanted to do more. But, like many busy people it seemed to me that trying to introduce even just Vespers on top of what I was already doing was going to be difficult. I was given an alternative. If at any time I could not recite a full Office, why not substitute it with a memorized prayer, and aim gradually to mark each Hour and aim for the ideal of sevenfold prayer each day?

I was helped by reading a book recommended to me by a fellow faculty member of Thomas More College of Liberal Arts called Earthen Vessels, the Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition, by Fr Gabriel Bunge. Despite its daunting title it is in fact quite easy to read and very practical. Fr Bunge a Swiss Benedictine monk explains that the essence of the liturgy of the hours can be described as two things: first praying the psalms; and second, the marking of an hour. The official ‘off-the-shelf’ cycles of psalms, canticles, hymns and prayers are produced to allow people to sing in community, and this is why priests and religious must say a prescribed form. However, as lay people, we are free to devise any cycle of the psalms we like.

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication Magnificat is a cycle of the psalms, with some prayers and canticles, that one can subscribe to monthly, which has been designed with lay people in mind.

So this is what I did: for the most part I tried to keep to the standard form of each Office as in the Liturgy of the Hours book I had been given (which was according the Roman Rite, it said in the front) and from that to the schedule of Compline at night and Lauds in the morning. However, in between I marked the hour with a short memorised prayer, sometimes just the Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be. If I could remember any, I tried to have just a line from a psalm. The ideal would be to memorise one psalm (and some are short!). This habit of continual prayer is what opens the door to the possibility of continuous prayer. The publication Magnificat is a cycle of the psalms, with some prayers and canticles, that one can subscribe to monthly, which has been designed with lay people in mind.

What are the Hours?

The hours are not set times according the clock, but to the traditional organisation of time in which, roughtly speaking, usual hours of daylight are broken up into twelve divisions. So it is roughly like this: Lauds at dawn or when you get up; Terce (the ‘third hour’)at 9am or mid-morning, Sext (the ‘sixth’ hour) at noon or the middle of the day, None (at the ‘ninth’ hour)at 3pm or mid afternoon and Vespers at dusk. Then there is Compline at bed time and during the night Matins, which is also called the Office of Readings. Because busy people are not expected always to be able to rise at midnight to praise God, this can be said at any convenient time and is often run together with Lauds, first thing in the morning.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

The experience of doing this has been so positive that I can't imagine not wanting to pray at least part of the Hours each day. As someone said to me recently, he found that the praying of the liturgy of the hours was like regular physical exercise: although it meant an investment of time, there was a sense that in doing so, time was created because work seemed more efficient and productive and things just seemed to go more smoothly during the day. We both felt the same. We couldn’t prove it, but once we had tried it, we were convinced of its value.

I started doing the liturgy of the hours about 15 years ago and gradually, I have found that my life circumstances have altered to give room for it. I don’t do it all perfectly, but I now do most Offices each day. It does not feel like a burden, but a source of sustenance.

Psalm 116

O praise the Lord, all ye nations: praise him, all ye people. For his mercy is confirmed upon us: and the truth of the Lord remaineth for ever.

You can read a more detailed article about it by following the link: Achieving the Pauline Ideal - Praying Continuously Body and Soul.

Those who want to learn to do the Divine Office, you might approach a priest or religious (ie monk or nun) and ask them to show you. Alternatively, the Way of Beauty summer retreats at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts will teach you how to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and how you can realistically incorporated it into a busy working or family life

Excavation of 1,500 year-old Church in Israel

Here are some photos of a recently excavated church in Israel, close to Jerusalem, that is thought to have been active between the 5th and 7th centuries AD. it has appeared in the a number of news sites. The account by AP, here comments on the floor mosaics of a lamb, cockerels, lions, fish and peacocks. When I saw the photographs, the geometric patterns in the floor design caught me eye too.

Here are some photos of a recently excavated church in Israel, close to Jerusalem, that is thought to have been active between the 5th and 7th centuries AD. it has appeared in the a number of news sites. The account by AP, here comments on the floor mosaics of a lamb, cockerels, lions, fish and peacocks. When I saw the photographs, the geometric patterns in the floor design caught me eye too.

Below is a floor mosaic from a Roman villa in Aldborough, North Yorkshire, England.

A decorative border from a mosaic in Pompeii

Praying with the Cosmos – the Ancient Treasury of the Divine Office I

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1, part 2 here The Divine Office (also called the Liturgy of the Hours), is one of the four pillars of the spiritual life of the new liturgical movement. This is the first in a regular series that highlight the riches of the the liturgy of the Church and how it is at the root of Western culture.

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1, part 2 here The Divine Office (also called the Liturgy of the Hours), is one of the four pillars of the spiritual life of the new liturgical movement. This is the first in a regular series that highlight the riches of the the liturgy of the Church and how it is at the root of Western culture.

'The Mass is a precious jewel and that jewel has its setting, which is the Divine Office. The Divine Office also has its setting, which is the cosmos.' This is how a priest who was visiting Thomas More College of Liberal Arts put it to me recently. In the picture of words he painted for us, the Divine Office mediates between the Mass and cosmos. Through its pattern of prayer, it highlights for us the rhythms and patterns of sacred time, which are reflected also in the cosmos. The cosmos points us not only to the Divine Office, through its order, but also through its beauty draws us in and lifts our souls to God in heaven. God's angels and His saints are praying the heavenly liturgy - this is the activity, so to speak, of the exchange of love with God in perfect and perpetual bliss. And through the Mass the heavenly and the earthly, the divine and the human meet and the otherwise impassable divide is bridged supernaturally. By it, can step supernaturally into the heavenly dimension.

The Divine Office is an often-forgotten ancient form prayer, which has its roots in the pre-Christian worship of the Jews. We can assume that as a devout Jew, Christ will have prayed it, and we know from the Acts of the Apostles that the tradition was continued by His Church. Priests and religious of the Church are obliged to pray it to this day and we would perhaps most commonly associated it with the chanting of monks and nuns. But it is not their preserve. In the past it was a widespread regular practice for most lay people also. The Church of today encourages lay people to pray this too placing it in value above all other prayers and devotions apart from the Mass. I was first encouraged to pray it by my spiritual director, one of the Fathers at the London Oratory, when I was living in England. It has been a life transforming experience for me.

In essence the Divine Office is simple. We say, or ideally sing, the psalms at regular intervals during the day, marking significant times called ‘Hours’. It is part of the Liturgy, the formal and public worship of the Church (like the Mass) and for this reason also known as the Liturgy of the Hours. If you want to pray with the priests of the Church then you can see each Office set out each day at www.universalis.com.

If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

Also, participation in the Liturgy of the Hours is an education in beauty. It impresses upon our souls the order of the cosmos and so enhances our creativity. Whatever your discipline, ideas that are in harmony with the natural order are more likely to occur to you in your daily work. For example, I wrote about how awareness of the symmetry of the natural order has already aided scientific research, in the field of particle physics, in a previous article called Creativity in Science through Beauty.

Those who want to learn about this can approach any priest or religious (ie monk or nun) and ask them what they do. Alternatively, the Way of Beauty summer retreats at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts teach us how to pray the Liturgy of the Hours and how you can realistically incorporated it into a busy working or family life. It also teaches us just how the heavenly order that permeates traditional Western culture and can again in the future. Those who are interested in more information about this should go here.

For a longer essay on this read The Cosmic Liturgy and the Mind of the Creator.

The painting at the top is Fra Angelico and the frescoes below are by Giotto. Note the stars in the sky. This is not just a device by an interior designer to make the space seem bigger by creating the illusion that there is no roof. This is deliberately encouraging in us the sense that the cosmos is praying with us and that the heavens point us to Heaven.

Part II is here.

Icons by Irina Gorbunova-Lomax

Here are some icons by a Belgium-based Russian icon painter. She has and exquisite touch in the graceful flow of the line that conforms to the prototype and describes form beautifully. Also, she skillfully handles the delicate overlay of washes of colour retaining a freshness and giving the sense that they were produced by a sure, well-guided hand. Her gallery,here, has examples of works done on paper or parchment, some having the appearance of studies for other works. These particularly highlight her drawing ability. I have shown a few examples below.

Here are some icons by a Belgium-based Russian icon painter. She has and exquisite touch in the graceful flow of the line that conforms to the prototype and describes form beautifully. Also, she skillfully handles the delicate overlay of washes of colour retaining a freshness and giving the sense that they were produced by a sure, well-guided hand. Her gallery,here, has examples of works done on paper or parchment, some having the appearance of studies for other works. These particularly highlight her drawing ability. I have shown a few examples below.

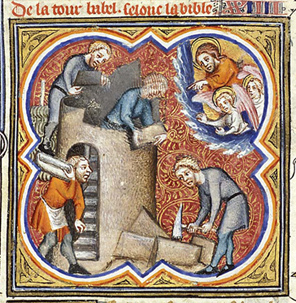

The Practice of Lectio Divina (3): Ephrem the Syrian on the Inexaustible Treasury of Scripture

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one here; part two here) This is from the Office of Readings of Sunday Week 6 of Ordinary Time. It is from a Commentary on the Diatassaron by St Ephrem the Syrian. It certainly inspires me to keep on reading the bible and makes this point that God speaks to me at the level I am at, and so the same piece of scripture can say different things to me on the next reading. The sub-heading is: God's Word is an inexaustible spring of life.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part three; part one here; part two here) This is from the Office of Readings of Sunday Week 6 of Ordinary Time. It is from a Commentary on the Diatassaron by St Ephrem the Syrian. It certainly inspires me to keep on reading the bible and makes this point that God speaks to me at the level I am at, and so the same piece of scripture can say different things to me on the next reading. The sub-heading is: God's Word is an inexaustible spring of life.

'Lord, who can comprehend even one of your words? We lose more of it than we grasp, like those who drink from a living spring. For God’s word offers different facets according to the capacity of the listener, and the Lord has portrayed his message in many colours, so that whoever gazes upon it can see in it what suits him. Within it he has buried manifold treasures, so that each of us might grow rich in seeking them out.

The word of God is a tree of life that offers us blessed fruit from each of its branches. It is like that rock which was struck open in the wilderness, from which all were offered spiritual drink. As the Apostle says: They ate spiritual food and they drank spiritual drink.

And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

And so whenever anyone discovers some part of the treasure, he should not think that he has exhausted God’s word. Instead he should feel that this is all that he was able to find of the wealth contained in it. Nor should he say that the word is weak and sterile or look down on it simply because this portion was all that he happened to find. But precisely because he could not capture it all he should give thanks for its riches.

Be glad then that you are overwhelmed, and do not be saddened because he has overcome you. A thirsty man is happy when he is drinking, and he is not depressed because he cannot exhaust the spring. So let this spring quench your thirst, and not your thirst the spring. For if you can satisfy your thirst without exhausting the spring, then when you thirst again you can drink from it once more; but if when your thirst is sated the spring is also dried up, then your victory would turn to harm.

Be thankful then for what you have received, and do not be saddened at all that such an abundance still remains. What you have received and attained is your present share, while what is left will be your heritage. For what you could not take at one time because of your weakness, you will be able to grasp at another if you only persevere. So do not foolishly try to drain in one draught what cannot be consumed all at once, and do not cease out of faintheartedness from what you will be able to absorb as time goes on.'

I have just one comment on the icon of St Ephrem. Ephrem lived from the first part of the 4th century and in 1920 was proclaimed by Pope Benedict XV as a Doctor of the Church. Among his famous writing are his Hymns of Paradise. The sunken cheekbones in the icon are used to show asceticism. Ephrem was not a monk as monasticism as we know it was only beginning to take hold in Egypt during this period. However, he lived in a Christian community that had similar disciplines and he is venerated in the East as an example of monastic discipline. Hence the sunken cheeks.

Monastery in the Syrian desert (this is of St Moses the Ethiopian). I hope their spring is inexaustible, just looking at it makes me feel parched!

The Practice of Lectio Divina - a Source of Joy (2)

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one, here) I am not an expert in this at all, but I thought that my experiences of trying (and often failing) to learn the technique and practice it, might be a starting point for others who wish to make a beginning also. Also I would encourage any of you who have experience to offer any helpful thoughts for the benefit of the readership…

Before I even began my investigation of lectio divina, the point was made to me that it is good to go to someone who can structure my spiritual life so that all of these things have a unity that allow them to nourish and support my ordinary daily activities. The danger is that I just tack one more devotion onto the daily list of personal obligations without proper understanding of how it relates to the other things that I do and the whole thing becomes a burden, in which I feel guilty if don’t tick all the boxes that day.

Scripture, Part of the Foundation of Joy (part two; read part one, here) I am not an expert in this at all, but I thought that my experiences of trying (and often failing) to learn the technique and practice it, might be a starting point for others who wish to make a beginning also. Also I would encourage any of you who have experience to offer any helpful thoughts for the benefit of the readership…

Before I even began my investigation of lectio divina, the point was made to me that it is good to go to someone who can structure my spiritual life so that all of these things have a unity that allow them to nourish and support my ordinary daily activities. The danger is that I just tack one more devotion onto the daily list of personal obligations without proper understanding of how it relates to the other things that I do and the whole thing becomes a burden, in which I feel guilty if don’t tick all the boxes that day.

Now for lectio divina itself: the first part is lectio. This just means reading. The first thing I have to do is select a passage to read. I was told to start with the gospels. If I aim to do it regularly, it was suggested that I try to go through the bible systematically, even if this means that it will take years to go through it once. One person told me another systematic approach to begin with is to pick the readings, or just the gospel reading, for Mass that day. If you don’t have a Missal to hand, www.universalis.com has the readings each day.

So having selected the passage I say a short prayer, that I might be receptive to whatever God wants to say to me through the passage I read. And then I read away. As phrases catch my attention I re-read. If nothing catches my attention, I just re-read the whole allotted passage a number of times. One helpful piece of advice given to me was that God will speak to me at the level I am at. So I shouldn’t worry that I am not a scripture scholar who isn’t instantly aware, for example, of the parallels between Old and New Testaments or the allegory that it contains, and so on.

However, it is a good idea, I was told to support this lectio, if I have time, with reading of commentaries on scripture, that my understanding might increase in time. I was told to be careful with modern commentaries as many (including some by Catholic writers) do not adopt a starting postion of faith that this is the inspired Word, and so a skepticism creeps into their work. I play safe and go for the Church Fathers and even here I let the Church guide me through her liturgy. The Office of Readings has a passage every day by a Church Father and very often this is a commentary on scripture. So I let the Church educate me as I worship God the Father in the Liturgy. Here is this dynamic, described yesterday, of Liturgy illuminating Scripture and Scripture intensifying my participation in the Liturgy. Again, the Universalis website is a great source for the Office of Readings each day.

However, it is a good idea, I was told to support this lectio, if I have time, with reading of commentaries on scripture, that my understanding might increase in time. I was told to be careful with modern commentaries as many (including some by Catholic writers) do not adopt a starting postion of faith that this is the inspired Word, and so a skepticism creeps into their work. I play safe and go for the Church Fathers and even here I let the Church guide me through her liturgy. The Office of Readings has a passage every day by a Church Father and very often this is a commentary on scripture. So I let the Church educate me as I worship God the Father in the Liturgy. Here is this dynamic, described yesterday, of Liturgy illuminating Scripture and Scripture intensifying my participation in the Liturgy. Again, the Universalis website is a great source for the Office of Readings each day.

The second part is meditatio. This means ‘I think’. This was always a source of confusion for me. In this age of post-Beatles, Maharishi Yogi pop culture, I thought that meditating on a phrase meant repeating it like a mantra in Eastern meditation. And that the goal was one of the elimination of thought; or at the very least it was a passive process of just letting my mind drift in the ethereal breeze and see what thoughts might crop up, but without reacting to them. I couldn’t work out what I was supposed to be doing here – it seemed to be contradictory to the idea of trying to understand the passage, which involved the application of reason to what was being read. My predicament wasn’t help by many of the books that I first read about Lectio Divina. Some (perhaps influenced by pop culture too) read as though they had been written by a beatnik writer who described it as an invitation for me to indulge in my emotions through undirected random or stream-of-consciousness style thought, on the assumption that because I had just read a bit of the bible, this was God at work in my mental processes. I was suspicious of this undirected approach.

The way out of this changed when I was told something about the distinction between Christian and Eastern, non Christian, ideas of meditation. Meditate, in the Christian tradition means more ‘meditate upon’, the same as ‘think’. So while in meditatio I do pause and allow for the prompting of the Spirit in the form of occurring thoughts and ideas; when they do occur I react to them by mulling over them, perhaps asking myself: what does this mean? Is there something that applies to me directly? How can I act on this in the rest of the day? And so on.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

This leads to the third stage, Oratio – prayer. So here I can ask God to show me how to act on something or help me in those areas that the meditation highlighted. The worry for me here was that sometimes I didn’t seem to have any profound lessons or thoughts to react to. This meant I didn’t know what to pray, except perhaps, ‘please give me some profound lessons or thoughts’. Here again I was given some helpful advice by someone with much greater experience than me. He said that quite often this happened to him and he didn’t think it was anything to worry about, he simply said some prayers in which he praised God for having this chance to hear his Word.

I find that once I start reading, I can move gently from one to the other, reading, thinking, saying a short prayer and then reading again.

The fourth part is contemplatio. This is contemplative prayer. As you can imagine, this originally caused me confusion too. I thought contemplation and meditation meant pretty much the same thing. And given the fact that I didn’t initially understand what meditation was, the inclusion of contemplation just compounded it even further. So I needed another explanation: in contrast to mediatio , this part is passive. It is passive in the sense that it is a state of mind that is given to us as a gift from God and actively pursuing it cannot guarantee its occurance. If I have understood the descriptions properly, it is a state of stillness of mind; one of just being with God and it sounds something like the descriptions of the beatific vision when we are in full union with God in heaven. However, as it is a gift from God, I should be careful in interpreting anything from about it or concluding anything about my spiritual development, or about how well I have done the first three stages. God either gives it to me or he doesn’t. Contemplation, therefore, is not a reward or goal of the first three stages, in that sense, it is just something that might happen, or it might not over which we have very little control. For myself, all I can say is that if it happened to me, I didn’t notice (which I’m guessing probably means that is hasn’t happened!).

The reason I do this is the reason that I am driven to do any of these things. I believe that ultimately and generally, I will be the happier for doing so, rather than any immediate reward of a pleasant emotion or feeling during the process.

At this point, I was going to include another passage from the Office of Readings at the end of this, but given the length of this piece so far, so I’ve decide d to tack on a Part Three, which will appear tomorrow. It is by the 3rd century Father, Ephraim the Syrian.

The Practice of Lectio Divina - a Source of Joy (1)

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow)

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow) Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Pilgrimage to a Forgotten Ancient Church in Matera, Italy

Matera is in southern Italy (just inland from the arch in the boot-shaped country). In the later classical period and through to the Middle Ages it has been occupied by Romans, Lombards, Byzantines, Germans and Normans and the handover was usually less than peaceful. The area is known for its underground churches, rather like the catacombs but dating much later. My former teacher when I was studying the academic method in Florence, Matt Collins, now lives there. Matt is an American and one of the few people around that I know who has applied his academic training to painting in the baroque style (as distinct from the 19th century). As well as oils, he is an expert in the technique of fresco and runs regular classes in Italy teaching this ancient and very durable technique.

The underground churches of Matera contain many frescoes and they have survived the Romans and all the waves of conquerers, only to be damaged recently by modern-day vandals and graffiti artist. What a shame! Matt describes them in his blog and it is his pilgrimage that the title refers to. The painting shown is Matt's landscape of the approach to the entrance of two underground churches. To read more about his, go to his article by following the link here. You can also see more of his work there too.

Matera is in southern Italy (just inland from the arch in the boot-shaped country). In the later classical period and through to the Middle Ages it has been occupied by Romans, Lombards, Byzantines, Germans and Normans and the handover was usually less than peaceful. The area is known for its underground churches, rather like the catacombs but dating much later. My former teacher when I was studying the academic method in Florence, Matt Collins, now lives there. Matt is an American and one of the few people around that I know who has applied his academic training to painting in the baroque style (as distinct from the 19th century). As well as oils, he is an expert in the technique of fresco and runs regular classes in Italy teaching this ancient and very durable technique.

The underground churches of Matera contain many frescoes and they have survived the Romans and all the waves of conquerers, only to be damaged recently by modern-day vandals and graffiti artist. What a shame! Matt describes them in his blog and it is his pilgrimage that the title refers to. The painting shown is Matt's landscape of the approach to the entrance of two underground churches. To read more about his, go to his article by following the link here. You can also see more of his work there too.

The photograph above is of the entrance to the ravine, and below, of the entrance to one of the churches in the hillside.

Inside with the apse with niche and altar

And finally, just if any are wondering what Matt's art is like here is a beautiful still life displaying the classic baroque stylistic element that readers of this blog will recognise - the variation in focus; the depletion of colour and reduction of contrast away from the natural foci of the composition.

Creating an Icon of a Modern Saint

With the announcement of the beatification of John Paul II someone sent to me this icon of him in which Christ presents the world to him. Painting an icon of a well known figure raises a number of considerations for an artist. How should an icon painter represent a likeness, especially when the person is someone whose face is so commonly recognized from photography, which doesn’t conform to the iconographic form?

When painting someone for whom there is already an established prototype in the tradition, such as Christ or the Apostles, the artist relies on that.

With the announcement of the beatification of John Paul II someone sent to me this icon of him in which Christ presents the world to him. Painting an icon of a well known figure raises a number of considerations for an artist. How should an icon painter represent a likeness, especially when the person is someone whose face is so commonly recognized from photography, which doesn’t conform to the iconographic form?

When painting someone for whom there is already an established prototype in the tradition, such as Christ or the Apostles, the artist relies on that.

The two requirements for a holy image were set out by Theodore the Studite. He is the great Father of the East whose writing, perhaps even more than John of Damascus, closed the iconoclastic period in the 9th century. The first requirement is that the image bears the name of the person depicted; and the second is that it captures his or her ‘characteristics’. I have written in more detail about this here. When we talk about ‘characteristics’ in this context, we are referring not so much to a photographic likeness, but rather to those key elements (which might include physical attributes) that characterize the person and contribute to his or her uniqueness as a person. So it would include, for example, the physical attribute of shaggy hair and beard of the prophet Isaias; but also the tongs and hot coal that touched his mouth before he prophesied for the first time.

When painting an icon of a modern figure for whom there no established iconographic prototype, the painter will have to judge what those characteristics are. Then he will have to decide how much of a ‘portrait’ it will be. I have seen some icons of figures such as St Therese of Lisieux in which a naturalistic photographic-portrait like face stares out from a painting in which everything is else iconographic. There is a clash of styles and is a blend of naturalism and iconography that doesn’t make sense to me.

In this example, the iconographer seems to have resisted this temptation and has created something that is consistent with his own iconographic style. In doing this he has sacrificed elements of a more conventional likeness. I think this is the better approach. Notice how similar the facial features of John Paul II are to those of Christ. I don’t know if this has been done consciously, or if it is just the iconographic style of the painter coming through naturally in both. Either way, to my mind the effect works. Christ is the Everyman, the model for all humanity, so it is right that all saints, especially, participate in his humanity. This is done without sacrificing the individuality of the John Paul II. We see….

I have a similar problem to grapple with as I continue to paint large scale works for the chapel at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts. In the next few months I will begin an image of St Thomas More himself. This issue here is not that his photographic image is well known, but that his naturalistic portrait is. The familiar painting by Hans Holbein the Younger, is the definitive face of Thomas More. As a portrait it is wonderful, but it is not right for an icon. At this stage, my intention, rather like the this artist, is to make sure that the name, the characteristics of man and the style are all preserved (in this case I will be attempting to work in a gothic style rather than iconographic). There is a line drawing study for a painting of the whole family that Holbein made. Given that iconography and the early gothic tends to describe form with line (in contrast, baroque and High Renaissance art describes form with tone) this maybe easier for me work from. We shall see!

Below I show a larger image of the icon above.

Concert of Music from the Sarum Rite

This is sacred music from pre-Reformation England. Sarum is old name for the town of Salisbury and it disappeared as a form of the Church's liturgy after the Council of Trent. However, it was retained in some form as it became the basis of Anglican church music and for the Book of Common Prayer. The concert takes place in a New York Episcopalian church - Trinity Church. I heard about it because it was posted onto my Facebook page by a TMC student who is currently out in Rome - thanks Taylor! Access the video through the image of Salisbury Cathedral below.

The Liturgical Life that will Create the Culture of Beauty

My colleague at the New Liturgical Movement website, Shawn Tribe, has posted a simple but truly wonderful and inspiring article about what he calls the 'pillars' of a liturgical life.He describes not a theoretical discussion for experts in liturgy, but rather simple practices for parish and family. It is a spiritual life based upon the Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours and study of scripture, especially through lectio divina. This, in my opinion, is the basis for cultural renewal. Shawn's article is a must read for anyone committed to the re-establishment of a culture of beauty in the West, especially those associated with the liturgical arts (and frankly for that matter everyone else too). This is the sort of practice of the Faith that has been called for by Popes (just to my knowledge) ever since Pius X at the end of the 19th century and right up to Pope Benedict XVI today. He emphasises particularly the importance of something so often neglected by lay people, the Liturgy of the Hours otherwise called the Divine Office.

Passing on a practical way of such a fruitful participation in the liturgy is the primary aim of the weekend retreat at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts this summer. It not only teaches about Shawn's pillars, but how to participate. It is expected that many will already have a strong sense of this in the Mass; but knowledge of a practical way that busy lay people can participate in the Liturgy of the Hours, and how Catholic culture is rooted in the whole of the liturgy is less well known. It is designed so that not only will everyone be able to continue practising what they learn after they leave, but will be able teach others in their family and parish.

My colleague at the New Liturgical Movement website, Shawn Tribe, has posted a simple but truly wonderful and inspiring article about what he calls the 'pillars' of a liturgical life.He describes not a theoretical discussion for experts in liturgy, but rather simple practices for parish and family. It is a spiritual life based upon the Mass, the Liturgy of the Hours and study of scripture, especially through lectio divina. This, in my opinion, is the basis for cultural renewal. Shawn's article is a must read for anyone committed to the re-establishment of a culture of beauty in the West, especially those associated with the liturgical arts (and frankly for that matter everyone else too). This is the sort of practice of the Faith that has been called for by Popes (just to my knowledge) ever since Pius X at the end of the 19th century and right up to Pope Benedict XVI today. He emphasises particularly the importance of something so often neglected by lay people, the Liturgy of the Hours otherwise called the Divine Office.

Passing on a practical way of such a fruitful participation in the liturgy is the primary aim of the weekend retreat at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts this summer. It not only teaches about Shawn's pillars, but how to participate. It is expected that many will already have a strong sense of this in the Mass; but knowledge of a practical way that busy lay people can participate in the Liturgy of the Hours, and how Catholic culture is rooted in the whole of the liturgy is less well known. It is designed so that not only will everyone be able to continue practising what they learn after they leave, but will be able teach others in their family and parish.

Although what is offered is at the grassroots level of one person praying with another. The ambition and hope we have of this high - the transformation of society. Any culture points to the cult at its centre, in the case of Catholics that is the liturgy. Accordingly, the demise of Catholic culture in the past points to large scale demise in the liturgical life in the Church militant (and we are talking about something here that happened long before the 1960s); and conversely the primary driving force for any cultural renewal will be liturgical renewal. What Shawn is describing is the basis, therefore, not only of the basis of liturgical renewal, but also cultural renewal.

The TMC weekend retreat is aiming to fulfill the final pillar listed by Shawn in his piece, and which informs the other three, that is 'mystagogy'. Mystagogy is, to quote Stratford Caldecott, 'the stage of exploratory catechesis that comes after apologetics, after evangelization, and after the sacraments of initiation (baptism, Eucharist, and confirmation) have been received' And it is necessary (here quoting Benedict XVI) because '"The Church's great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one's life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world. For this reason, the Synod of Bishops asked that the faithful be helped to make their interior dispositions correspond to their gestures and words. Otherwise, however carefully planned and executed our liturgies may be, they would risk falling into a certain ritualism.'

Read Shawn Tribe's article here.

..and here is a newly discovered 15th-century Coptic icon

![]() Shawn Tribe who writes at the New Liturgical Movement website just posted this image. It is a newly discovered ancient icon.

Having described Stephane Rene's neo-Coptic style as a more polished form of the 'folksy' original Coptic style, here comes something to disprove my point! This is 15th century but it reflects high level of drawing skill. One of the great difficulties when I paint in the iconographic or the gothic style is conforming to the style, yet still managing to have the figure to read anatomically and the clothing to drape naturally so that the folds reflect the figure underneath. The artist seems to have taken great care, for example, with the blue shawl of Our Lady to do this.

Shawn Tribe who writes at the New Liturgical Movement website just posted this image. It is a newly discovered ancient icon.

Having described Stephane Rene's neo-Coptic style as a more polished form of the 'folksy' original Coptic style, here comes something to disprove my point! This is 15th century but it reflects high level of drawing skill. One of the great difficulties when I paint in the iconographic or the gothic style is conforming to the style, yet still managing to have the figure to read anatomically and the clothing to drape naturally so that the folds reflect the figure underneath. The artist seems to have taken great care, for example, with the blue shawl of Our Lady to do this.

The Coptic Church is one of the Oriental Orthodox churches. The Oriental Orthodox churches are those Christian bodies that broke away with Rome in the wake of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, over disagreements on the christological doctrines affirmed by that council. The Oriental Orthodox churches include the Armenian Apostolic, Syrian, and Coptic Orthodox—but not the larger Russian, Greek, and other Orthodox churches of the Byzantine tradition. The Pope has fostered dialogue with these ancient churches. CatholicCulture.org writes about this here.

![]()

Two More Neo Coptic Icons by Dr Stephane Rene

Further to the recent posting about a Coptic style Stella Maris icon, here are two more icons by Dr Stephane Rene in his ‘neo-Coptic’ style. They were sent to me by two people who read the previous article. St Joseph of the House of David and Mary Mother of the City are in St Joseph’s Catholic church, in Bunhill Row in the City of London. I remember this Church because it is just around the corner from the offices of the Catholic Herald, where I once worked. They come courtesy of a reader who brought them to my notice. So if you're reading thank you Martin Pendergast, and to you Sr Jean for supplying the images.

Further to the recent posting about a Coptic style Stella Maris icon, here are two more icons by Dr Stephane Rene in his ‘neo-Coptic’ style. They were sent to me by two people who read the previous article. St Joseph of the House of David and Mary Mother of the City are in St Joseph’s Catholic church, in Bunhill Row in the City of London. I remember this Church because it is just around the corner from the offices of the Catholic Herald, where I once worked. They come courtesy of a reader who brought them to my notice. So if you're reading thank you Martin Pendergast, and to you Sr Jean for supplying the images.

The name derives from the fact that St Joseph, although poor was of the Royal House of David. There are four narrative scenes from the gospel in each corner. The one of the Holy Family in a boat is depicting them on the Nile - representing the period of exile. Notice also the beautiful patterned border that Dr Rene has designed.

Where can Catholics Go to Learn to Paint in the Naturalistic Tradition?

If you are interested in the baroque, where do you go to learn to paint? In a past article I wrote about possible places to study the iconographic technique in depth. However, the baroque is also one of the three liturgical artistic traditions of the Church (the third is the gothic) and anyone who is serious about being an artist for the Church should consider whether they want to learn this form. One place to consider is Ingbretson Studio in Manchester, New Hampshire.

If you are interested in the baroque, where do you go to learn to paint? In a past article I wrote about possible places to study the iconographic technique in depth. However, the baroque is also one of the three liturgical artistic traditions of the Church (the third is the gothic) and anyone who is serious about being an artist for the Church should consider whether they want to learn this form. One place to consider is Ingbretson Studio in Manchester, New Hampshire.

The ideal education would consist of the following: first, a Catholic formation (perhaps studying a liberal arts degree at a Catholic college); second a sound knowledge of the Catholic traditions in art. For those who wish to learn this aspect in isolation the Maryvale Institute’s excellent distance-learning programme Art, Inspiration and Beauty from a Catholic Perspective is recommended. They are about to offer this in the US, through the Diocese of Kansas City, which saves students on this side of the Atlantic from a trip over to the UK for the one weekend residential requirement. Full-time undergraduate-level students can receive both of these aspects at the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire by taking their liberal arts degree which includes my Way of Beauty program as part of the core syllabus.

The third aspect is to learn the drawing and painting skills. The skills are those of the academic method. This is the rigorous drawing method that is named after the schools that were created in the 16th and 17th centuries (especially that of the Annabale Carraci, his brother Agostino and his cousin Ludovico. The method has its roots in the methods used by the Masters of the High Renaissance going back to Leonardo. This method is different and far more rigorous than that offered in the drawing classes in a mainstream college-level art department.

This training usually begins with cast drawings because casts have no colour and so the eye learns to ‘see’ in tonal values. The cast are carefully chosen to be model examples of beautiful sculpture. This way the taste of the student is developed as well as his skills. After this students progress onto the use of colour; perhaps through portrait painting or still life (I did portrait painting). The value of an academic training cannot be underestimated. It is being able to draw and paint accurately that enables the artist to realize his ideas. Whatever style he seeks to work in he needs a high level of skill so that he can create an image that conforms to what it ought to be, corresponding to the well conceived idea in the mind of the artist. Even my icon painting teacher Aidan Hart encouraged me to study naturalistic art for a year in Florence saying that all the best icon painters were also skilled draughtsmen. I do not regret following his advice.

This training usually begins with cast drawings because casts have no colour and so the eye learns to ‘see’ in tonal values. The cast are carefully chosen to be model examples of beautiful sculpture. This way the taste of the student is developed as well as his skills. After this students progress onto the use of colour; perhaps through portrait painting or still life (I did portrait painting). The value of an academic training cannot be underestimated. It is being able to draw and paint accurately that enables the artist to realize his ideas. Whatever style he seeks to work in he needs a high level of skill so that he can create an image that conforms to what it ought to be, corresponding to the well conceived idea in the mind of the artist. Even my icon painting teacher Aidan Hart encouraged me to study naturalistic art for a year in Florence saying that all the best icon painters were also skilled draughtsmen. I do not regret following his advice.

Most of the schools that teach this method now are termed ‘ateliers’ after the French word for workshop. They are small schools in which the main teacher is a Master painter. A few were established in the 1970s by individuals taught by an artist called R.H. Ives Gammell in Boston, who at that stage was an octogenarian. Gammell, who trained as a young man in the early years of the 20th century, almost singlehandedly kept the academic tradition going after all the art schools in Europe and the US had ceased to teach it. The best teachers of today that I know of (on both sides of the Atlantic) received their training from him.

If you want to investigate the available ateliers yourself, a starting point is the Art Renewal Centre website, where you can run down the list of approved ateliers. Do be discerning. Have a look at the work by students and teachers in their galleries - this will indicate the style that they will teach you. It is important that you respect what is going to be passed on to you. From my point of view, while many of these ateliers will train you to draw, there is a danger in some tend to push a particular version of 19th century academic art that is detached from Christian worldview. If you are not careful this could affect your style detrimentally. The result will be either the extreme of a cold, sterile detachment (a form of neo-classicism) or a the end of a saccharine sentimentality.

If, on the other hand, you are armed with a full knowledge of the Christian context of this tradition (such as the courses at TMC or the Maryvale Institute would give you) you should be able to make good use of the skills you learn. You can contrast some aspects of 19th century atelier art with the baroque style of the 17thcentury by reading these two articles, written earlier, here and here respectively.

Another problem which would be a concern for some is that one cannot assume that a taste in traditional art necessarily means that a traditional attitude to faith and morality pervades in the atelier you attend. Many have a hostile attitude to the Catholic faith and morality, and students will have to be ready to face this just as they would in more conventional art schools. Quite apart that an immoral atmosphere is undesirable in itself, the worldview of the artist affects the style in which he paints, whether done consciously or not. When studying n an atelier, we take precise direction via the critiques of the Master who runs it. For the period that you are his student, your work reflects his taste and style. Having the humility to be told what to do in such minute detail is a necessary aspect of the training. However, if this taste and style reflect values that are flat contrary to your own, then the learning process is not such a happy one. As a quick test, take a look again at the online galleries of work, especially paintings of the human person, at those same ateliers listed on the Art Renewal Centre. Ask yourself in each case if you think that the figure has been portrayed with the dignity that reflects the Catholic understanding of the human person.

Another problem which would be a concern for some is that one cannot assume that a taste in traditional art necessarily means that a traditional attitude to faith and morality pervades in the atelier you attend. Many have a hostile attitude to the Catholic faith and morality, and students will have to be ready to face this just as they would in more conventional art schools. Quite apart that an immoral atmosphere is undesirable in itself, the worldview of the artist affects the style in which he paints, whether done consciously or not. When studying n an atelier, we take precise direction via the critiques of the Master who runs it. For the period that you are his student, your work reflects his taste and style. Having the humility to be told what to do in such minute detail is a necessary aspect of the training. However, if this taste and style reflect values that are flat contrary to your own, then the learning process is not such a happy one. As a quick test, take a look again at the online galleries of work, especially paintings of the human person, at those same ateliers listed on the Art Renewal Centre. Ask yourself in each case if you think that the figure has been portrayed with the dignity that reflects the Catholic understanding of the human person.

The one place that I know of in which the training is of the highest quality and that Catholics can flourish without compromising their faith in any way is Ingbretson Studios in Manchester, New Hampshire. Paul Ingbretson is a modern Master of the Boston school and is one of those I mentioned who was given his training by Ives Gammell in the 1970s. He has been teaching ever since. His school has an international reputation (we were all well aware of it, for example, when we were studying in Florence).

For those who are about to go to college but don’t want to leave their art behind while they study a traditional liberal arts programme at a Catholic college, Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is the one place where you can study both. By coincidence Ingbretson Studios is just 10 minutes drive from the TMC campus. This semester, undergraduates have been able to choose to study academic drawing for a full day a week. Those who have a strong enough interest will also have an opportunity to train full time for three solid months each summer if they wish to do so. This is part of the college art guild of St Luke in which students are able to learn also traditional iconography and sacred geometry.

The painting at the top is The Incredulity of St Thomas painted in 1620 by Gerrit van Honthorst, which is in Madrid's Prado.

The photographs above are of the first drawings by students on the Thomas More College summer programme, which is taught by Henry Wingate, a former student of Paul Ingbretson, and which is repeated this summer. These represent about 5 full days' work.

The photographs below are of Thomas More College students on their first day at the Ingbretson Studio this past week. Notice how when they draw they are not looking at the cast. They are drawing from memory. Standing a few feet back, the compare drawing and cast and decide what original mark or correction to make, then they walk forward and draw it. Having done this they then retreat, once again to compare drawing and cast to see if what they did was correct. And the process is repeated over and over again.

The photograph above is of a still life setup by a more senior student at the Ingbretson Studio, and below are a couple of finished student cast drawings.

A Coptic Icon of Stella Maris

![]() Dr Stephane Rene, who painted this icon, is a contemporary artist trained in the Coptic tradition. He is based in London and teaches at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts. Many Coptic icons I have seen have a rough folksy feel to them. Stephane Rene’s however have a flow, grace and polish that goes beyond that and he describes his style as ‘neo Coptic’.

This particular icon has been blessed by Pope Benedict XVI. I especially like the monochrome designs in the decorative border (for those who are surprised that this should be on an icon, I refer you to a previous article ‘Why Frame a Picture?’.

Dr Stephane Rene, who painted this icon, is a contemporary artist trained in the Coptic tradition. He is based in London and teaches at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts. Many Coptic icons I have seen have a rough folksy feel to them. Stephane Rene’s however have a flow, grace and polish that goes beyond that and he describes his style as ‘neo Coptic’.

This particular icon has been blessed by Pope Benedict XVI. I especially like the monochrome designs in the decorative border (for those who are surprised that this should be on an icon, I refer you to a previous article ‘Why Frame a Picture?’.

I could not get hold of a large image to paste into this article. But readers can see one here as well as an article about the commission from the Apostleship of the Sea, which presented it to the Pope in Rome to be blessed.

![]()

![]()

Glory Be to God for the Brompton Oratory

The magazine Dappled Things asked me to write about an occasion when I had been affected by the beauty of a sacred place. I decided to write about my first ever experience of the liturgy at the London Oratory (also known at the Brompton Oratory). This sublime experience opened the door first to my conversion and then, beyond that inspired me to try to contribute to the re-establishment of a Catholic culture of beauty rooted in the liturgy. (I have always had an attitude that if you aim high then even if you only make it half way, that that's still quite good.)

Normally people have to subscribe to their online edition, but they decided to make an exception for this special edition. It is one of the features under the heading Sacred Places.

The magazine Dappled Things asked me to write about an occasion when I had been affected by the beauty of a sacred place. I decided to write about my first ever experience of the liturgy at the London Oratory (also known at the Brompton Oratory). This sublime experience opened the door first to my conversion and then, beyond that inspired me to try to contribute to the re-establishment of a Catholic culture of beauty rooted in the liturgy. (I have always had an attitude that if you aim high then even if you only make it half way, that that's still quite good.)

Normally people have to subscribe to their online edition, but they decided to make an exception for this special edition. It is one of the features under the heading Sacred Places.

Relief Carving - Painting in Shadow

The tradition of the Eastern Church is not to have statues in its churches. A statue occupies three-dimensions of space, unlike a painting, which only occupies two-dimensions (but can create the illusion of a third). Given that the iconographic form, which is the only artistic liturgical tradition that the Eastern Church will permit, seeks to eliminate as far as possible even the illusion of a third dimension, that is depth, it is hard to imagine how statues (in which the third dimension fully exists) could be created in accordance with the iconographic form.

The development of statues for churches came in the West in tandem with the desire to create the illusion of space in two-dimensional representations, generally identified with the beginning of the gothic period in about the 12th century. This did not cause the tradition of relief carving to die out in the West. It has always flourished in both Eastern and Western churches

The tradition of the Eastern Church is not to have statues in its churches. A statue occupies three-dimensions of space, unlike a painting, which only occupies two-dimensions (but can create the illusion of a third). Given that the iconographic form, which is the only artistic liturgical tradition that the Eastern Church will permit, seeks to eliminate as far as possible even the illusion of a third dimension, that is depth, it is hard to imagine how statues (in which the third dimension fully exists) could be created in accordance with the iconographic form.

The development of statues for churches came in the West in tandem with the desire to create the illusion of space in two-dimensional representations, generally identified with the beginning of the gothic period in about the 12th century. This did not cause the tradition of relief carving to die out in the West. It has always flourished in both Eastern and Western churches

Relief carving in effect, is a monochrome painting in shadow. So although there is a physical deviation from a strict two-dimensional representation not as a statue does, by imitating the three-dimensional shape, but rather by creating the illusion of depth by altering the tone of the shadow. Where the shadow is to be black (or darkest) the cut is deep and the surface angle close to perpendicular to the broad plane of the image. Where a grey or mid-tone is required, the cut is less deep and the surface angle somewhere in between, depending on how dark or light the artist wishes to make it appear. Where the tone required is white (or lightest possible) the surface faces us directly and is parallel to the broad plane of the image.

The conventional classification of relief carving is a division into bas relief (bas in French is low) and alto (ie high) relief. In the first the cut is shallow and there is no undercutting so that representation is never more than half in the round. Alto relief is where there is undercutting and so there are some elements that are carved more than half in the round. Sunken relief, or intaglio, is where the negative space around the figures is flat and the figures are cut out from it below that surface. For more information on this see article here.

Some might point out that the reason we can perceive form in a conventional statue that is not painted, for example all marble is due to shadow too. This is true. But the difference here is that the shadow is revealing is the true shape of the statue, which in turn imitates the idea in the mind of the artist. Whereas, in relief carving it paints, so to speak, the illusion of depth.

As with all these things, the division between the different techniques is never absolute. Bernini, the great baroque sculptor used to deviate from a strict representation of appearances in his statues and exaggerate certain elements by cutting deep into the stone and creating sharper contrast. He would say that as he didn’t have colour to manipulate the gaze of the viewer, shadow was the main tool that he had.

Below and above, Byzantine 10th century, St Demetrios

6th century Armenian, Virgin and Child

The Magi, Amiens Cathedral, 13th century

Station of the Cross: the English artist, Eric Gill, 20th century, Westminster Cathedral